I love discovering the meanings behind the names given to medieval dishes. Call me scholar, call me nerd, I just can’t help myself.

Many of the recipe titles in Richard II’s official cookery book, Forme of Cury (c. 1390), have bamboozled antiquarians and academics for centuries, so I get a kick out of working out what they may mean. It’s not always possible to be absolutely sure about some of my conclusions, and sometimes I simply reach a dead end, but with a spirit of persistence, I am finding more of these names are indeed making better sense.

In this, my fourth Language of Cookery note, I am looking at the name ‘Bursews’, one of the last recipes in Forme of Cury.

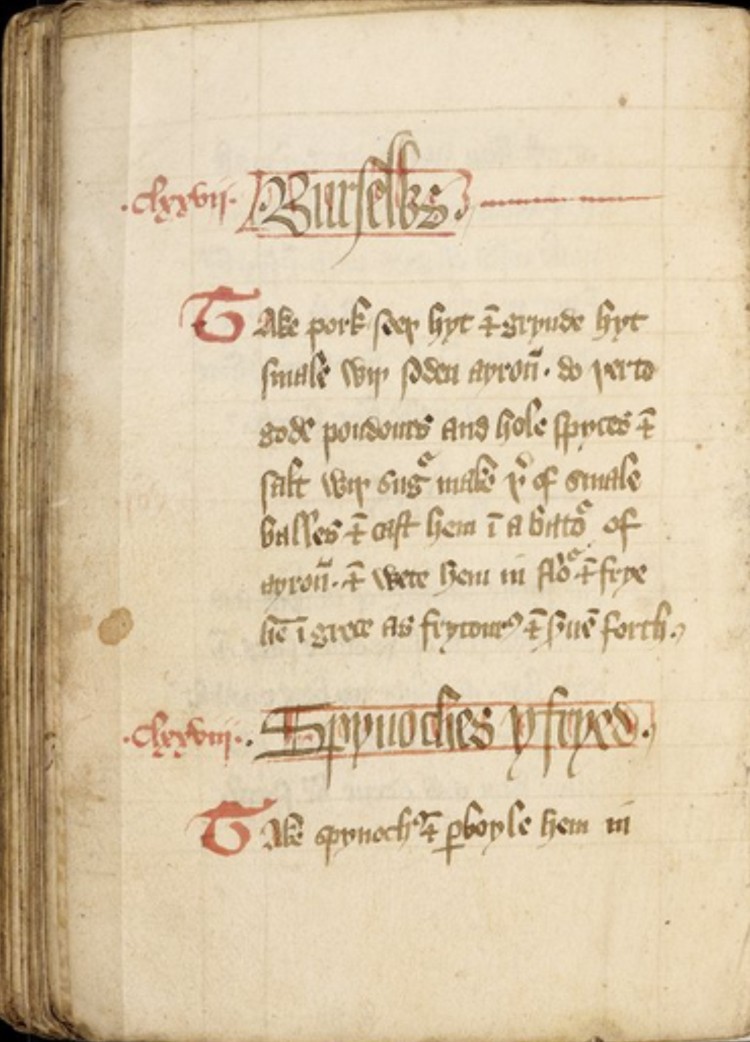

The Middle English Dictionary (MED), though often so very useful, doesn’t yield up much help in this case; it simply states that burseu (the singular form) was a ‘dish of minced meat’. That much is self-evident from our ‘Bursews’ recipe, one of four the MED refers to as examples. Here’s my edition of the text from the John Rylands copy along with my translation:

Bursews

Take pork, seeþ hyt & grynde hyt smale wiþ soden ayroun, do þerto gode poudours and hole spyces & salt wiþ sugur, make þerof smale balles & cast hem in a batour of ayroun, & wete hem in flour & frye hem in grece as frytoures & serue hem forth.

Take pork, simmer it and grind it finely with boiled eggs; add to this good powders and whole spices and salt with sugar; from this make small balls, and cast them into a batter of eggs, and roll them wet in flour, and fry them in fat as fritters, and serve forth.

Text and translation by Christopher Monk © 2020

The next go-to source of information is the 1985 edition of Forme of Cury, published by the Early English Text Society.¹ This edition, by Constance B. Hieatt and Sharon Butler, bases its text on various versions of extant copies of Forme of Cury, primarily the well-known British Library roll, dating to the 1420s, but also several fragmentary texts.

However, at the time, the editors were not aware of the John Rylands copy, which later Hieatt recognised ought to have been their base manuscript as in many respects its copy of Forme of Cury was the ‘best’, and likely the earliest, of the surviving versions.² The information Hieatt and Butler provide in their edition is very interesting, though ultimately this doesn’t point to a clear understanding of the name ‘Bursews’.

In their edition, they plump for the name ‘Ruschewys’, found in some of the fragmentary versions of Forme of Cury, but they note that both the British Library copy and another manuscript roll, kept in the Morgan Library of New York, have ‘Bursews’.

So what on earth are ‘Ruschewys’? Well, this word is a variant plural form of the Middle English risheu (MED), which means ‘rissole’. According to the MED, risheu derives from Old French.

Pertinently, it appears in Anglo-Norman, the dialect of Old French used in England, mostly in elite circles, after the Norman Conquest (1066). It is attested to in various forms including russchole, which you will notice has the same -sch- element as the Middle English recipe name in Hieatt and Butler’s edition (you can check this at the online Anglo-Norman Dictionary [AND]: enter russchole into the search box).

One important culinary observation I should make at this juncture about medieval rissoles: when we take a look at the examples of meat-based rissoles in Middle English recipes, most seem to wrap the meat mixture in pastry before frying, whereas our ‘Bursews’ recipe doesn’t do this. This does seem to suggest there was some considerable variance — or confusion — in the way rissoles were understood back then, as there is indeed today, as I shall address at the end of the post.

But this digression into ‘Ruschewys’ doesn’t remotely help us with understanding what ‘Bursews’ means. Since it doesn’t take a genius to recognise that the two names hardly seem related, we need to do a little more etymological digging, unless we want to go down the path of declaring some peculiar, though unlikely, error of scribal transmission.

But we don’t need to do that, because there is a far more satisfying answer:

If we look to Anglo-Norman again, we can see the similarity of Middle English bursews to Anglo-Norman bursus, which is the plural form of burs meaning ‘purse, money-bag’ (go to AND: insert burs into the search box). Indeed, it is my understanding that the two words would likely have been pronounced very similarly in the fourteenth century.

Anglo-Norman burs found its way into Middle English as burse, ‘pouch, purse’. Ultimately, both the Anglo-Norman and Middle English derive from Latin bursa which, too, has as one of its meanings, ‘purse, money-bag’. Even today, modern English has the Latin-derived words bursar and bursary which, of course, are both related to money, and the modern French word for ‘purse’, in the sense of ‘money’, is bourse.

When we take a look at the actual recipe of ‘Bursews’, we note that the dish is essentially fried ‘small balls’ of meat. This name seems to be alluding to the round, purse-like shape of the food — remember purses in the fourteenth century were little pouches of leather tied at the top, creating a round receptacle in which to place one’s coins. (There’s a great picture here of a late medieval purse found in Coventry.)

That the name of our recipe should be just a simple allusion to the shape of the dish’s components is reinforced when we realise that both the Middle English word burse and its Latin cognate bursa were used for other roundish, pouch-like things, including testicles and haemorrhoids!

So, folks, I could have gone with ‘Testicles’ as my recipe name, but ‘Purses’ seemed a rather more palatable choice.

Finally, I promised to look at modern-day rissoles a little more closely, and in particular their variant incarnations.

It seems fair to say that the likes of our ‘Bursews’, balls of minced meat, battered and fried, were the forerunners of these British delicacies.

My Scottish partner informs me that rissoles and chips were a big thing in Scotland when he was a lad (40+ years ago), a culinary delight of every chippy (chip shop). These rissoles were apparently made from a mixture of potato and minced beef (or possibly corned beef); they were rather more sausage-shaped than ball-shaped; covered in breadcrumbs rather than battered; and, of course, in line with the likely medieval method, deep-fat fried — ah, the Scots love their deep-fried foods!

According to Wikipedia’s informative entry for rissole, these are still going strong, bread-crumbed or battered like our ‘Bursews’, in Ireland, Wales, north-east England, and in Yorkshire, too, where fish often substitutes for meat.

Beyond the British Isles, meat rissoles are popular in Australia and New Zealand (see the image above). And elsewhere there are versions of meat or fish rissoles in Portugal and Brazil — crescent-shaped and covered in breaded pastry (recipe here) — and also in Indonesia, where meat, or chicken, and vegetables are the main part of the filling (recipe here).

I look forward to making some medieval rissoles/’Bursews’ myself, or should that be meat purses?

Notes:

1. Curye on Inglysch: English Culinary Manuscripts of the Fourteenth Century (Including the Forme of Cury), edited by Constance B. Hieatt and Sharon Butler, Early English Text Society, Special Series 8 (Oxford University Press, 1985).

2. See Hieatt’s discussion of the Rylands Library copy: note especially, at p. 46, her admission that it ought to have been the base manuscript for their edition, and her discussion of the dating of its handwriting to the fourteenth century at p. 47.

Always interesting stuff here! And I do applaud your choice of translations for the title! The other, in this context, would have made me think of Rocky Mountain Oysters and the like. Yuck. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha ha ha! ‘Haemarrhoids’ is not much better, either.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, just the man to ask! I’ve made jowtes in almond milk which I’ll be posting about soon, but I can’t find any reason or translation for the word ‘jowtes’ other than taking historians at face value when they say ‘jowtes in almond milk’ is basically herbs (like leeks) in almond milk. I wonder if you can tell me what jowtes are and if it does just mean ‘herbs’, why?

Love reading your blog, by the way. I always learn so much!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the comment and question.

Yes, ‘jowtes’ or ‘joutes’ (and other spellings), the plural of ‘joute’, does mean herbs chopped up for making a sauce/stew/soup/pottage, or indeed the dish itself. ‘Joute’ is a borrowed word from Anglo-Norman (again spelt variously: ‘jute’, ‘jote’, ‘joute’) where it is used both in singular and plural form to mean a soup or pottage made using vegetables or herbs. Ultimately, the derivation is medieval Latin (not classical Latin), where ‘juta’ means a soup/stew. Interestingly — and this is where my nerdy curiosity kicks in — medieval Latin ‘jota’ means a ‘pot-herb’ or ‘vegetable’. Now, my brain is asking, if there may be a connection between medieval Latin ‘jota’ and ‘iota’, the transliteration of the 10th letter of the Greek alphabet and also used to mean ‘the least part…jot’: could the herbs, chopped up so fine as they are, allude to ‘iotas’ or ‘jots’ of vegetation floating about in one’s pottage/sauce/stew/soup? I may be on an etymological fantasy trip, here, so please don’t quote me on this, so I may have to ask a few people, cleverer than me, to see what they think.

Hope that was fun for you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was genuinely fascinating, thank you for taking the time to explain it! I used chives in my soup, and they did float like little jots so I think you could be right, it certainly sounds plausible to me (although I don’t have any kind of linguistic background!) So would I be right in thinking that a ‘joute’ is a word that we’ve lost to time, rather than an early form of a word in use today?

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s right.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Unless my jot/iota theory is right 😁.

LikeLiked by 1 person

(‘Joute’ as a lost meaning for herb, not jot or iota!)

LikeLike

Interestingly, the loan word ‘herbe’ (‘herb’) was in use in Middle English. The Old English (pre-Conquest) word which could be used to mean ‘herb’ or ‘vegetable’ was ‘wyrt’ which survives today as ‘wort’ in names of plants. I can’t remember if Old English ‘wyrt’ survived alongside the Anglo-Norman loan words in Middle English. I need to check.

LikeLike

Yes, ‘wort’ survived into Middle English, generally meaning ‘plant’.

LikeLike