I must own that I have a sweet tooth. And were I back in the fourteenth century, a VIP guest at Richard II’s table, I would be munching on his comfits with unbecoming gusto.

Comfits are sugar-coated, or candied, seeds and spices. During King Richard’s time, they were often white but also coloured – red from saunders (a kind of sandalwood), for example.

They might be used as a flourishing decoration to an otherwise plain looking dish: blank maunger (a rice pudding with ground capons) comes to mind, its whiteness enhanced by jewels of red anise comfits. Or they would appear at the end of a meal on elegant spice plates, perhaps viewed as an aid to digestion.

In Forme of Cury, King Richard’s official cookery book, both red and white comfits of anise (aniseed) and red comfits of coriander are given as ingredients. The latter, rather oddly it has to be said, were served with what I can only describe as a watery broth with lasagne.

Losyns in fysch day

Take almaundes unblaunched & waische hem clene, drawe hem vp wiþ water; seeþ þe mylke & alye hit vp with losyns; cast þerto safroun, suger & salt & messe hit forth wiþ colyaundre in confyt rede & serue it forth.

Lasagne on a fish day

Take unblanched almonds and wash them clean [and grind them], blend them with water; simmer the [almond] milk and combine it with lasagne; add to this saffron, sugar and salt, and arrange it forth with red comfits of coriander seed, and serve it forth.

Forme of Cury, edited and translated by Christopher Monk © 2020

Now, this was a recipe for a fasting day (the meaning of ‘fish day’), but were it not for the pops of sugary coriander I can well imagine diners dying of saintly boredom consuming such a bland affair.

How were comfits made?

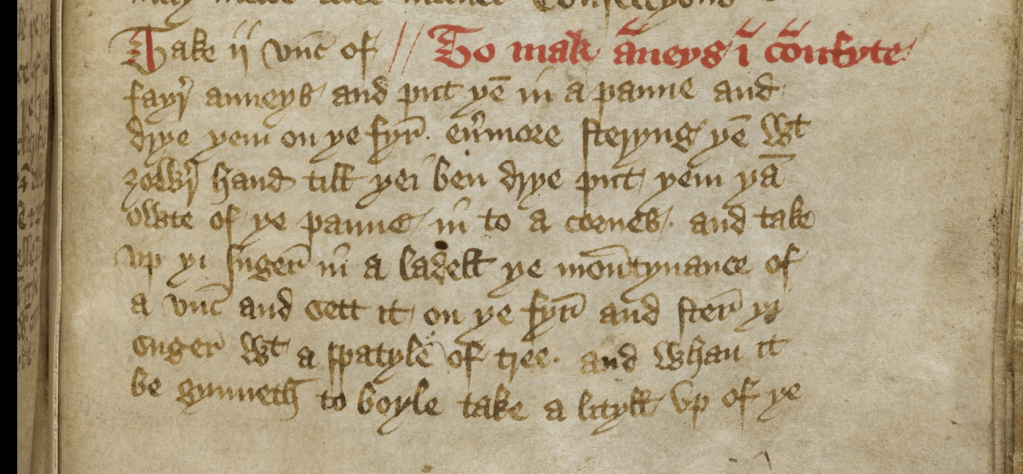

Forme of Cury offers no recipe for comfits, so to discover how medieval cooks went about producing these necessities of life, we turn to a roughly contemporary miscellany in which, among other culinary, medical and alchemical texts, can be found this gem:

To make comfits of anise. Take 2 ounces of fair anise and put them in a pan and dry them on the fire, continuously stirring them with your hand, until they are dry. Then put them out of the pan into a vessel [cornes].

And take up your sugar in a ladle, the amount an ounce, and set it on the fire; and stir your sugar with a wooden spatula; and when it begins to boil take up a little of the sugar between your fingers and thumb, and when it begins any time to stream then it is cooked enough.

Then remove it from the fire and stir it a little with your spatula, and then put your anise into the pan with the sugar, and continuously stir inside the pan with your flat hand, slowly, continuously on the bottom, until they separate. But make sure you stir them, and briskly, when they stick together.

And then set the pan over the stove again, continuously stirring with your hand, and with the other hand continuously turn the pan in order to keep the heat even [literally, ‘for cause of more heat on the other side’] until they be hot and dry. But make sure that it does not stick on the bottom. And also, as you see that it is going again on the bottom, remove it from the stove and continuously stir with your hand; and put on the stove again until it be hot and dry.

And in this manner, you shall work it up until it [i.e. each anise seed] becomes as big as a pea, and the greater that it waxes [i.e. grows] the more sugar it takes.

And each time put in your pan a decoction [decoccioun]. And if you see that your anise wax rough and ragged, give your sugar a lower decoction, for the high decoction of the sugar makes it rough and ragged.

And if it be made of pot sugar, give them 4 decoctions more above, and at each a decoction of 2 ounces of sugar: and this is more or less, it is not exact.

And when it is worked up at the last stage, dry it over the fire, stirring continuously your hand, and when it is hot and dry remove it from the fire and stir it off the fire, slowly with your hand along the pan bottom until they are cold, for then they will not change their colour. And then put them in containers [coffins], for if you put them into containers whilst hot, they will change their colour.

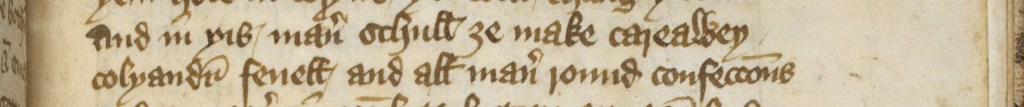

And in this way shall you make carraway, coriander, fennel, and all manner of round confections, and ginger in comfit; but your ginger should be cut like a dice in small pieces, four-square; and give your ginger a little higher decoction than you give the other seeds.

Translation © Christopher Monk 2020. Translated from the edited text by Constance B. Hieatt and Sharon Butler, Curye on Inglysch (Early English Text Society, Oxford University Press, 1985), pp. 12-13.

The method is reasonably straightforward, though a few terms and phrases need explaining:

Decoction

Translating Middle English decoccioun, this refers to the sugar reduction, that is, the syrup that is formed by heating the sugar in the pan. A ‘lower’ decoction refers to a less dense syrup than the ‘higher’ decoction: the sugar is boiled for less time and is more pliable.

The method given implies that the desired effect was a smooth candy coating of the seeds, although, post-medieval, ragged comfits were evidently popular, as we can deduce from this seventeenth-century still life, by Georg Flegel, showing a mouse sniffing at some decidedly roughed-up sweeties.

It is also possible that the square ginger comfits mentioned at the end of the recipe were intended to be more ragged, since a higher decoction was recommended for those.

Take up a little of the sugar between your fingers and thumbs

Unless you wish to remove the epidermis from your digits, I strongly urge you not to duplicate this instruction literally, should you be attempting to make comfits yourself.

What is actually meant, I understand, is to take some of the boiling sugar syrup with your spatula (or a spoon) and drop it into a bowl of cold water to see how it behaves, and then subsequently use your fingers and thumb to ascertain how soft and pliable the sugar syrup is.

If you take a look at this video by the BBC (the BBC are always right on these serious culinary matters), you can see the three different stages of sugar syrup. The first stage, the ‘soft ball’ stage, seems to show the syrup streaming as it hits the cold water, and when handled is still very pliable.

This is what our medieval comfits cook was looking for, it would seem. As the layers were built up, presumably the sugar coating would harden, but not before a nice, smooth finish was obtained. Leave the syrup too long when boiling it, and pearly comfits would have been out of the question.

Having said this, the Elizabethan God of Candy, Sir Hugh Plat, in his chapter on ‘The arte of comfetmaking’, found in his irresistably titled work, Delightes for Ladies (first published in 1602 but inevitably with that title re-printed numerous times), informs us:

But for plaine comfits let your Sugar be of light decoction last, and of a higher decoction first, and not too hote.

Sir Hugh Plat, Delightes for Ladies (1602). Text reproduced from Oakden.

So, it would seem, Sir Hugh was aiming for an initial harder coating of his seeds than perhaps our medieval confectioner was, though he cautions us not to make the sugar too hot.

continuously stir inside the pan with your flat hand, slowly, continuously on the bottom, until they separate

This sounds a risky business. Instinctively, I would keep my hand as far away as possible from hot sugar syrup. That said, this does seem to be suggesting that the comfit creator was meant to rub the seeds with the palm of their hand in order to move them about the pan and coat them evenly in syrup.

That this is not completely insane, we may look again to Sir Hugh Plat. He tells us:

At the first coate put on but one halfe spoonfull with the ladle, and all to move the bason, move, stirre and rubbe the seeds with thy left hand a pretty while, for they will take sugar the better, & dry them well after every coate. Doe this at every coate, not only in moving the bason, but also with the stirring of the comfits with the left hand and drying the same.

Sir Hugh Plat, Delightes for Ladies (1602). Text reproduced from Oakden.

So Hugh seems quite explicitly to advocate the use of not just stirring, but rubbing the seeds with the left hand in order for them to take on the sugar syrup better. Perhaps the contact between palm and hot sugar was brief, a sort of medieval culinary analogue of walking with bare feet on coals. But, please, replicate this at you own peril. When I get around to making comfits, I will be using a flat wooden spatula!

pot sugar

This was basic sugar of the lowest quality, coming below ‘black’ sugar, actually brown; ‘Caffatin’, a refined white sugar; and, at the top of the sugar mountain, the most refined white sugar known as ‘blaunk’ (see C. M. Woolgar, The Culture of Food in England 1200-1500, Yale University Press, 2016, p. 96).

It seems that the cook had to make an adjustment if using this inferior sugar, but what exactly is meant by ‘give them 4 decoctions more above’ when using pot sugar is unclear. It may mean that 4 more coatings were added compared to when using decent sugar, ‘described above’ as it were. And since two ounces per decoction rather than the one were to be used, this seems to underscore the need for more sugar overall when using the cheap and nasty. I say, you get what you pay for, medieval comfit maker: just use the posh stuff!

I do hope you have enjoyed this little foray into the world of medieval, cavity-inducing delights. I would love to know if any of my readers have attempted making comfits. If so, do let us all know in the comments, or on my Facebook page. I promise to add these sweet treats to my culinary to-do list. And when (or if) I manage to perfect them, I may post a video of me eating them. All of them. By myself.

Donation

If you enjoyed reading this and other posts, please consider making a donation. Your donation will help me to continue with high quality, independent research. If you wish to donate using paypal.me, my link is paypal.me/drcjmonk.

3.00 $

Make a one-time donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is truly appreciated. It helps me to continue with high quality, independent research, including the writing of my book How to Cook in the Fourteenth Century: Richard II’s Forme of Cury.

Christopher

This is so thorough! Thank you, I had no idea about decoction at all.

I actually tried to make some aniseed comfits a while ago – I think I lasted 15 minutes before I gave up. Too fiddly for me!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m going to have a bash at making some. Fingers crossed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fingers crossed and WELL out of the way of that hot syrup…. Enjoyed this post, but it made me decidedly nervous. !!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me too! Thank you.

LikeLike

I’ve made a number of pounds of comfits since 2004 and, after briefly stirring the seeds with a wooden spoon/spatula/scraper, have been able to stir them with my hand. The longer they are dried, the whiter they become, most having started out a little grey. Here’s an article that I wrote up: http://damealys.medievalcookery.com/Comfits.html . Yes, comfits are fiddly and time-consuming. One trick is to not add too much syrup each time. (A friend in the Hampton Court kitchens admitted he had little patience so he just sort of dumped spoonfuls of sugar one!) Ivan Day recommends a limit of 10-15 “charges” (layers) each day so it can take quite a while to build up the size. I’ve gone as high as 70 chargers for one batch of comfits. I have found that, for smooth comfits, the temperature of the syrup should be fairly low. (See article.) This can involve juggling the syrup on and off the fire. Also, a wok makes a nice pan for working the seeds. Just be sure not to have the wok touch the heat. I have an electric range so I use the metal ring that can be purchased with a wok just to lift the pan off the heat. Would be glad to chat with any who have questions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for sharing your experience making comfits. I will be taking on board your tips when I have a go.

LikeLike

And thank you for the link to your blog post. It’s really helpful.

LikeLike

Great article and throughly enjoyed! Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

When we visited Hampton Court back in the winter, the only cook present was making comfits. He agreed that it took ages and thought it was probably the sort of job you did when the master of the house was away so you could spend all day on it. Wish there was a modern source which didn’t use the bright artificial looking colours that the Indian ones tend to be. I do not have the time to make my own, but they would be very useful for some of our demonstrations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I’m going to have to find the patience of a saint! Thanks for leaving a comment.

LikeLike

Well, comfits are one kind of treat that don’t have to be made all at one time. When you finish getting one set of 10-15 coats (“charges”), you can set them aside pretty much as long as you want before you go back to them. The only thing you would be “out” is the sugar syrup which can’t be saved from week to week. Some sources say to add the coloring agents to the last set of charges. Specific coloring agents for historic comfits include “brazel” for a reddish color, saffron for yellow, beet juice (beet leaves, not the red bulb) for green. Hampton Court has used parsley “water” for green. As you may have surmised, natural coloring agents would be more expensive and time-consuming for modern companies to use. I wonder if using modern cake decorating colors would work when added to the sugar syrup? One might be able to modify the depth of the color to approximate the medieval natural coloring agent.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This seems an excellent idea to pause between coating sessions. I will try saffron as well as white ones. I have a fair amount of parsley in my garden so will try green ones too; parsley is certainly used as a food colourant in other Forme of Cury (14th-century) recipes. Thank you so much!

LikeLike

Does your reference to “pot sugar” mean molasses? It sounds like it, light or dark.

LikeLike

Hello and thanks for the question. I don’t think so. It seems to refer to an “inferior” granular sugar, evidently unrefined. I’m not a sugar expert though. However, the reference I give from Woolgar’s book doesn’t define it as molasses. May I ask why you think it may be referring to molasses? And what do you mean by molasses? To me molasses is ‘black treacle’ (UK), a byproduct of sugar refining, so its a viscous rather than granular product. But I understand there is such a thing as molasses sugar which is similar to dark muscovado.

LikeLike

Joy! I found a reference to “pot sugar” in a translated Dutch cookbook. You can find the pertinent line here: http://medievalcookery.com/search/display.html?einno:158 Translation says “Item. All red sugar is pot sugar. And pot sugar is melted sugar. And melted sugar is meal sugar.” There is a link to the Dutch cookbook on that page. As Christopher Monk notes, it might be an “inferior” sugar. When medieval sugar went through the refining process, the aim was to get the highest quality of sugar: white sugar.

As I understand it, during the process of refining, the impurities of the cane sugar were removed in several steps before the refined sugar was poured into the traditional funnel-shaped clay containers where the remaining impurities would drip out from the bottom opening, the sugar crystals would fully dry, and the “sugar cone” would be shipped to consumers. Unfortunately for the consumer, not all sugar completed the removal of impurities and drying process. Sometimes, although the exterior of the resulting sugar loaf looked dry/crystallized, the interior was still wet – liquidy – with sort of an impure sludge (which wasn’t useable). Even if the sugar loaf were completely dry, the consumer may have purchased one of the lower qualities of refined sugar rather than the more expensive “pure white” varieties.

Until refining became more “refined” (technologically advanced) and the sugar less expensive, many confectioner recipes include instructions on “to clarify sugar”. This was an attempt to remove even more impurities and end up with a product that was appropriate for confections. (My hunch is that any regular sugar use in a cooked food rather than a confection didn’t bother “clarifying” the sugar. Confectioners and cooks were two different occupations and skill sets!) Confections required a high quality, white, sugar. If I may, here is a link to an article I wrote in the early 1990s which list a number of sugar types/qualities, and includes two methods of clarifying sugar for removing the last bits of impurities. I don’t believe that those impurities are what we call molasses or treacle. Manufacturing molasses/treacle is a different process, is relatively modern, and is past my time of interest. Here’s the link to my article which may “clarify” things about medieval sugars. http://damealys.medievalcookery.com/On_Powdered_Sugar.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for this information. I will definitely read your article. I’ve included in the glossary of the book I’m writing a translation of a 14th-century sugar clarifying method. It’s not in Forme of Cury. Forme of Cury does, as you say, include recipes that say to clarify sugar first. Thanks again.

LikeLike

Your article is excellent. Thank you. You do mention molasses as a sugar product that eventually came into being. I haven’t yet come across any 14th-century or earlier recipes using it.

LikeLike

Nor have I seen anything (that I can remember!) in English cookery books up to around 1650 when my collection peters out. While the internet is not a totally reliable source of information, I found this reference: “The English term molasses comes from the Portuguese melaço which in turn is derived from the Latin mel, meaning honey. Melasus (sic) was first seen in print in 1582 in a Portuguese book heralding the conquest of the West Indies.” https://tinyurl.com/y5fvfoug

I don’t have many Portuguese sources and, from re-reading that quote, it appears to not be from anything related to cookery or confections. The Encyclopedia Britannica, fairly reliable I would think, merely tells the process of separating the sugar from the liquid by means of a centrifuge. It doesn’t seem to say when the “molasses” was used in foods. https://www.britannica.com/topic/molasses

LikeLiked by 1 person

My gut says the etymological link to Latin *mel* seems dodgy. I’ll take a look at this tomorrow. Thanks again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Regarding 14th-century recipes using molasses/treacle, all I’ve been able to find so far are comments about treacle being used in medicine. There does appear to be shipment of treacle into England separate from sugar. Here’s one source: English Medieval Industries: Craftsmen, Techniques, Products, edited by John Blair, Nigel Ramsay

Page xxxii

“In 1390-1 Ships brought into London cargoes of such things as ivory, mirrors, paxes, armour, paper (none was made in England for another century), painted cloths, spectacles, tin images, razors, calamine, treacle, sugar-candy, marking-irons, paten (or clogs; 7,000 in one cargo alone, ox-horns and quantities of wainscot (boards. [80] https://tinyurl.com/yyp9ntuj

Another mentions treacle in the privy wardrobe of Edward III, definitely not a culinary use, although it could be medicinal. https://tinyurl.com/y24her9v

“The Senses in Late Medieval England”, C. M. Woolgar, Christopher Michael Woolgar

“Other odour-producing items were scarce even in the fourteenth-century royal household. Among the goods in Edward III’s privy wardrobe received by John de Flete on taking office were a basket with various phials of balsam, treacle and oil of St Katherine – some doubtless with a medicinal purpose, but some also with a strong odour; three phials of balsam were recorded among the goods used for the almonry and chapel. [159]

So far, no mention of treacle/molasses in food, but it was imported and used for (medicine??).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you’re on your way to an article here with everything you’ve dug up. This is very interesting.

I’ve been meaning to get Woolgar’s book. The English Medieval Industries I’d not heard of, but it looks like a must buy too.

LikeLike

Just on the Dutch reference. It’s somewhat obscure to my modern mind. It seems to suggest it was ‘red’ in colour, perhaps meaning brown? But what to make of ‘pot sugar is melted sugar’? That it was melted before going into the pot? And what’s meal sugar? That it was ground into sugar meal before use perhaps? Umm… 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m stumped as well about “meal sugar”. I think I’ll see if some other people might know. Perhaps the translation from Dutch is a bit wonky?

Hazarding a guess on “red sugar”, I wonder if it might be some of the darker colors of sugar that could be obtained. Less refined? Slightly different process? Turbinado sugar might have had a reddish-brown cast. That was a less refined sugar.

Here’s a modern look at “traditional” red sugar from the Orient: https://www.taikoosugar.com/en-us/products/detail/38 Another internet site references “red sugar” but might not pertain to medieval Dutch sugar: https://chemistry.stackexchange.com/questions/19593/difference-between-white-sugar-brown-sugar-and-red-sugar Looks like there is a “rabbit hole” to dive into!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sharing these links. Yes a rabbit hole leading to an extensive warren, no doubt!

LikeLike

Another branch of the rabbit hole: Found this from the mid-1500s about the types of sugar that were available. It mentions “brown” sugar being the “very worst of all the kindes”. Note that the apothecaries call it Saccharum rubrum. Would that “rubrum” refer to “red”? Here is the portion of the material that is pertinent:

This text describes the six types of sugar available circa late 16th century. Source: Wirsung, Christof, 1500 or 1505-1571. The general practise of physicke (which was finally published in 1605 after the author’s death). These are the two types relating to the current discussion.

The fifth kind is a browne and soft Sugar, it is brought from the Island S. Thomas, and it is the very worst of all the kindes: it is called of the Simplicistes Saccharum Thomasinum, Saccharum Thomaeum, and at the Apothecaries Saccharum rubrum.

The sixt kind is the sirup that floweth from the Sugar in refining, it is knowne euery where by the name of Sirupe, Mel Saccharinum and Remel. Whensoeuer any mention is made of Sugar, then is either the Made∣ry sugar, or the Malta sugar to be taken and vsed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s brilliant. Thank you so much.

Yes, ‘Saccharum rubrum’ means ‘red sugar’. So now we know that ‘pot sugar’ is brown, unrefined sugar, known as ‘red’ by the apothecaries.

The sixth sugar is interesting; I suspect this is referring to molasses. I need to follow up on the language elements. ‘Sirupe’ in the Middle English Dictionary doesn’t have mollasses; the Latin just means ‘honey (of) sugar’ but I can’t yet find Remel in any dictionary.

Thanks again. I will need to thank you in my book. Let me know how you want to be named.

LikeLike

Replying to your comment on the post above, “The sixth sugar is interesting; I suspect this is referring to molasses. I need to follow up on the language elements. ‘Sirupe’ in the Middle English Dictionary doesn’t have mollasses; the Latin just means ‘honey (of) sugar’ but I can’t yet find Remel in any dictionary.” If I may be so bold, I would be VERY careful using the term “molasses”. It is fraught with overtones of today’s USA “molasses”, probably moreso than with the term “treacle”. Historic cookery re-creators seem to look for any excuse to use modern day “molasses” and claim that there is “proof” for its use pre-1650 or so. I wish I could recall having seen the use for “sirup that floweth from the Sugar in refining”, but it’s blank. I wonder if that liquid might have been used in some beverages that don’t generally appear in cookery books. I have a mental picture from reading other material of buyers being disappointed (unhappy?) at finding the core of their purchased sugar loaves to be liquid and not the sugar crystals they thought they were getting. Did they discard that liquid (presumably the 6th kind?) or did they use it for something in order not to waste it? Are there any records of people purchasing this sirup from the refineries as a discrete item, not as a problem in a sugar loaf? Too many branches in the rabbit hole!

I appreciate your wishing to include my name in your book. My modern name is Elise Fleming. I will ask a librarian friend if she can find “Remel” in the sources she has.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, caution noted. Thank you, Elise.

LikeLike

Well, my caution about “molasses/treacle” might need a cautionary note. Johnna Holloway, librarian extraordinary, found “remel”! It’s from 1751 and uses both molasses and treacle as alternate names. However, in the quote from the book, below, this “remel”, even in 1751, is considered unpleasant and “ought to be rejected.” The book (title abbreviated) is “A new treatise on British and foreign vegetables…”, Étienne François GEOFFROY, 1751, and is on page 415. Here’s the pertinent part about “remel”.

“The thick, fat, red or brownish Liquor which falls from the Moulds can only be (inspissated) to the Consistence of Honey: Wherefore it is called Syrupus Saccharinus, Mel Saccharinum, Mellago, or Remel, commonly Melasses and Treacle. It is useless both in Food and Physick, and ought to be rejected. Yet some of the Confectioners make use of it, when clarified, for preserving red Fruits; but it is unfit for that Purpose on account of its Taste, which is something unpleasant. Some draw it from an Aqua Vitæ or flammable Spirit. They usually put one Part of Melasses to eight Parts of hot water with a little Ale-yeast, and mix them perfectly together: Afterwards they set them to ferment in close Vessels, till a subtile, spirituous and vinous Smell exhales from them; and then draw off an ardent Spirit by Distillation.”

There are pages and pages prior to this section in the Google book online which details the whole sugar and refining process. https://books.google.com/books?id=rbhgAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA415&lpg=PA415&dq=Mel+Saccharinum+and+Remel&source=bl&ots=bIQmCqLeTI&sig=ACfU3U3VnsFlgYvgciXF9TY8EjHrPrUvLA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj3n9rK0dfsAhUQCs0KHe0JCvQQ6AEwBHoECAkQAg#v=onepage&q=Mel%20Saccharinum%20and%20Remel&f=false

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is very interesting. I would read this as remel as some form of treacle/molasses but which this writer finds objectionable but others not. When I think about it black treacle (UK) is not that pleasant by itself — it has a bitterness that some might dislike — but which works when combined with other sugars and in baked goods.

LikeLike

I don’t know that it makes a difference, but what I read in that paragraph is that the “molasses/treacle” is what was inside an incompletely cured sugar loaf and not something that is purposely made for itself. The author says it should be discarded. At some point, I would guess, refineries got better at making just sugar and then found a purpose – or a process – to make something separate from the liquid but which still kept the name of molasses/treacle and which would then be sold as a separate product. From my admittedly amateur point of view, I would hazard that molasses/treacle was not an ingredient in foods or confections until sometime after this 1750s book. (There are a number of enthusiastic recreationist cooks who believe that if something exists today, then it existed back in the Middle Ages. I would hate for the reference to molasses/treacle to “prove” that our modern product was actually used for cookery before, say, the 1750s. Am I out of line? I guess the next rabbit hole is finding out when there is an early mention of molasses/treacle being produced and sold as a separate product.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you make a good point. I like your rrasoning. And the thing about names of things is that they can be reappropriated or shift in meaning. If I’ve learned one thing since venturing into food history is that you need to be careful with words and names. I think this remel is most definitely a byproduct of medieval, and early modern, sugar production. We don’t have sufficient evidence to equate it with molasses or black treacle production today, and later evidence points to it being considered unpalatable by some and as something to be discarded. Thanks once more for your observations. It’s very stimulating having these discussions. I can see you writing another article, on molasses!

LikeLike

Hadn’t thought of an article on molasses, but am now intrigued. The online Google book, “A new treatise on British and foreign vegetables…”, 1751, has a very detailed description of how sugar cane was refined. I think one hint is that the process only involved boiling processes. Modern molasses seems to involve a final step with a centrifuge. That might be the turning point from the throw-it-away molasses/treacle to a product that becomes saleable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And please thank Johanna Holloway!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I will thank Johnna Holloway. In all honesty, if my name is mentioned, hers should be as well. I shamelessly pick her brains when I can’t find any references!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know her name. I’m not sure why. Which library is she at?

LikeLike

Johnna Holloway has retired now but was a librarian at the University of Michigan, if I recall correctly. I’m not sure where you might have heard her name. She is listed on the “Concordance of English Recipes” and worked on the completion of the concordance by rechecking sources, etc. She writes articles for various newsletters in the living history group we both belong to. And, she has an impressive library! She still has access to many research sources from her active time as a librarian.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been diving into the rabbit hole. Here are some points and a hint about meal sugar.

1. I would agree that “red sugar” probably referred to the reddish-brown of a lower quality, less-refined sugar.

2. The ultimate problem is what is “meal sugar”? The Dutch reference seems to be A equals B equals C. If Woolgar is correct, pot sugar would be the lowest form of sugar available which was also called “red sugar”.

3. Would it be logical or correct to then assume that the use of this low quality of sugar would be in melted/liquid form?

4. And, from that, would it be understood that this form of sugar was used, in melted form, for cooking or meals? (Pot sugar, in the recipe would be in melted form for the comfits.)

5. I looked quickly into van Tets translation and found this extra item: “[14] Item. All red sugar put in dishes must boil with the dish into which one puts it or in which it belongs.” That would seem to fit with the idea that red sugar (A) is pot sugar (B). Pot sugar (B) is melted sugar (C) and melted sugar (C) is sugar meal (D) and must be boiled with the dish it is intended for. Does this help at all? Is the progression logical?

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds very logical. And most recipes which have sugar as an ingredient do not specify clarifying. Thank you. This is very helpful.

LikeLike

New hint about that Dutch reference to red/pot/meal sugar. A Facebook respondent wrote: “According to this, the Dutch definition (translated to English) for meelsuckere is Sugar that came from crushed and then crushed sugar loaves. Cf. powdered sugar. http://users.telenet.be/willy.vancammeren/NBC/nbc_glos_m.htm “

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, thank you.

LikeLike

Ah, yes, I read something about centrifuge. I think you’re right to point out the difference between medieval and modern “molasseses”.

I think I may be getting Johnna Holloway mixed up with someone else. Though I was at the University of Michigan for a week when I won a prize to attend a workshop on the medieval book for postgraduate students, back in 2008/9. Perhaps her name lodged in my brain. Which would be weird as I’m rubbish with names.

LikeLike

You probably came across my name in connection with the late CB Hieatt as I worked with her on the Concordance and on a bibliography for OUP. A number of my articles and edited/annotated cookery books can be found on medievalcookery.com. As a point of correction, I was never on the staff here at the UM, but was a faculty spouse,

LikeLike

Hello. Thank you for letting me know. Ill take

LikeLike

… (oops, fat fingers on my phone). I’ll take a look at your work. Thanks for sharing this.

LikeLike