I have been writing chapter 5 of my book (working title: How to Cook in the Fourteenth Century) which is dedicated to the sauce and condiment recipes in Richard II’s Forme of Cury. One of these recipes, ‘Galentyne’ in the Middle English text, intrigues me.

The main reason for the fascination is that this particular recipe (no. 136 in the John Rylands Library manuscript) is rather different from the galentines that appear elsewhere in the king’s cookery book as part of other dishes of cooked meat, poultry or fish.

Let’s then first take a look at this recipe. As you will see, there is no recommendation of what to serve it with.

Galentyne (136)

Take crustes of brede & grynde hem smale; do þerto poudour of galyngale, of canel, of gynger, and salt it; temper hyt with vyneger & drawe it vp þorow a straynour & messe hit forth.

Galentine

Take crusts of bread and finely grind them; to this add powder of galangal, cinnamon and ginger, and salt it; temper it with vinegar, and blend it through a strainer, and serve it forth.

Text and translation © Christopher Monk 2020

As you can see, this in an uncooked ‘sauce’. After making some myself, it seemed to me that this galentine was more condiment than sauce, something in the realm of mustard. Or let me put it another way: with its only liquid being vinegar, you wouldn’t want to pour it all over your roasted swan. A dab on the side, yes, but more than that would smother the flavour of the food any good sauce should enhance.

Galentine experiment

I ground up dried galangal root and dried ginger root along with a pinch of coarse salt with my pestle and mortar. I added ground cinnamon, some bread* and white wine vinegar and continued to pound it into a paste in the mortar. Finally, I passed the mix through a sieve.

Taste profile: zingy and acidic, with rather nice lingering notes of warm spices. I left some until the next day (uncovered in the fridge) and ate it with smoked ham and a vintage cheddar (no peacock or swan available). The acidity had mellowed and it made a really good alternative to mustard.

*I used gluten-free bread because I’m gluten intolerant; you could use a good white wheat flour bread, which is similar to what was used in Richard II’s kitchens; fresh or a little stale would work.

Image: © Christopher Monk 2020

This galentine, then, is not the cooked, broth-based sauce that characterises other galentine dishes. Let’s take a look at some of these others in Forme of Cury in order to show the difference.

pork in galentine

First is Fylettus in galentyne (recipe no. 28): this is part-roasted fillets of pork (cut from the hind legs) further cooked in a sauce that is ‘a mixture of bread and blood and broth and vinegar’ seasoned with ‘powder of pepper and salt’.

Another version of this dish (spelt ‘Fylettes in galyntyne’) appears later (recipe no. 115). It’s quite similar: it uses broth and bread, strained through a cloth, and pepper is again the spice of choice; however, red wine is substituted for the vinegar, and there is no blood used; further additions are onions, sanders (used as a red food colourant), parsley, hyssop, white fat (i.e. lard), and raisins.

Both of these galentine sauces share with our galentine condiment the use of bread as a thickening element and the deployment of a spice for some heat. In the pork galentine dishes, there is an element of acidity, via the vinegar or wine, but it seems quite evident that this would be relatively muted compared to our very sharp galentine condiment.

fishy galentines

Gynggaudy (recipe no. 92) is a green-coloured fish offal dish (I know you’re all loving the sound of this). In order to create its sauce the cook uses the broth in which the stomach and liver of various fish have been parboiled; and then to this adds wine and ‘a mixture of bread and galentine’ as well as spices and salt. The parboiled fish offal is returned to the broth to finish cooking and the sauce is thickened with wheat starch and coloured green, likely with parsley and/or sage.

The ‘galentine’ here appears to refer to gelatinous juices, most likely from a fish-based broth. I’ll return to this later in order to amplify the meaning of galentine, but for now you can see that we have a more recognisable sauce compared to the vinegary galentine condiment.

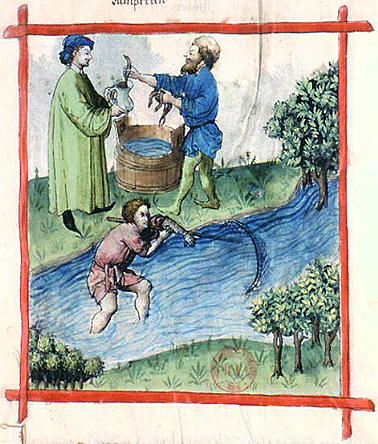

Launpreys in galentyne (recipe no. 124) is a dish of spit-roasted lamprey (a fresh-water eel-like fish)* in a galentine sauce that contains: ground currants blended with vinegar, wine and bread crusts; powdered ginger and galangal, cassia buds, powdered cloves; whole currants; and the blood of the lampreys and the collected fat from their roasting.

After salting this sauce, the instruction is given to ‘boil it not too thick’ and to arrange the roasted lampreys onto a charger and to ‘pour over the sauce’ (‘lay þe sew onoward’). Thus, once more, we have a ‘proper’ sauce. Like our galentine condiment, it does have acidity, from the vinegar and probably the wine, but this is lessened by the addition of the lampreys’ blood, and in reality bears little comparison to its uncooked namesake.

Young lampreys, ‘Laumprouns’, are cooked in galentine in the following recipe (no. 125). This sauce is a simpler affair, made from the broth in which the juvenile lampreys have been parboiled, which is then spiced with galangal and ginger powders, and seasoned with salt. No bread is added to thicken the sauce. As with the mature lamprey dish, the instruction is given to lay the fish in dishes and to ‘pour the sauce over’ (‘lay þe sewe aboue’).

(*My thanks to Dr John Wyatt Greenlee for kindly correcting my understanding, i.e. that a lamprey is not actually an eel, as I’d written in the first outing of this post.)

Fishing for lampreys

From a 15th-century copy of Tacuinum sanitatis. Image public domain, Wikimedia Commons: for image credit and licencing information, please click here.

So what are the common denominators between our cold and hot galentine sauces? Well, spices of some sort are used in them all, though that’s hardly distinctive, since spices are an element of most, if not all, of Forme of Cury‘s sauces.

We could highlight the fact that all but one of the galentines uses bread as a thickening agent and also that some level of acidity is obtained in most of the sauces through vinegar or wine. However, these too are not characteristics unique to galentine sauces.

To get closer to understanding why these sauces are called galentine, we need to look to French medieval cookery.

Jellies

Pork in jelly

This is rustic Gelatina di maiale, ‘pork jelly’, known in Sicily as Liatina. Back in medieval France they were doing something similar. Image: Wikimedia Commons; for credit and licence information, please click here.

Middle English galentyne (and its variant spellings) is a loan-word, from Old French galantine (sometimes spelt galentine). According to the Old French-English Dictionary, it means ‘jelly’, or ‘aspic’, the substance obtained by allowing broth made from boiling fish, meat or poultry to cool and set.

It is the gelatin in the broth that causes it to set into jelly once cooled, and we will have seen the effect of gelatin when we put home-made stock or a proper meat gravy overnight in the fridge: the liquid sets into a wonderful wobble.

Now to understand the origins of galentine sauces we need to understand more about French jellies. So let’s take a look at the fourteenth-century French cookery book, today known as the Viandier (‘recipe book’) of Taillevent, written by Guillaume Tirel (alias Taillevent), the chief cook of King Charles V of France (reigned 1364-1380).

Here we have a fairly lengthy recipe for ‘Fish and Meat Jelly’:

68. Gelee de poisson…: Fish and Meat Jelly. Take any fish whose skin is covered with a natural oil, or any meat, and cook it in wine, verjuice and vinegar – and some people add a little water (var.: a little bread); then grind ginger, cinnamon, cloves, grains of paradise, long pepper, nutmegs, saffron and chervil [?] and infuse this in your bouillon, strain it (var.: tie it in a clean cloth), and put it to boil with your meat; then take bay leaves, spikenard, galingale and mace, and tie them in your bolting cloth, without washing it, along with the residue of the other spices, and put this to boil with your meat; keep the pot covered while it is on the fire, and when it is off the fire keep skimming it until the preparation is served up; and when it is cooked, strain your bouillon into a clean wooden vessel and let it sit. Set your meat on a clean cloth; if it is fish, skin it and clean it and throw your skins into your bouillon until it has been strained for the last time. Make certain that your bouillon is clear and clean and do not wait for it to cool before straining it. Set out your meat in bowls, and afterwards put your bouillon back on the fire in a bright clean vessel and boil it constantly skimming, and pour it boiling over the meat; and on you plates or bowls in which you have put your meat and broth sprinkle ground cassia buds and mace, and put your plates in a cool place to set. Anyone making jelly cannot let himself fall asleep. If your bouillon is not quite clear and clean, filter it through two or three layers of a white cloth. And salt to taste. On top of your meat put crayfish necks and legs; and cooked loach, if it is a fish dish.

Terence Scully (ed.), The Viandier of Taillevent : An Edition of All Extant Manuscripts (University of Ottawa Press, 1988), p. 287. (Note: the italics in Scully’s translation represent variations in the various manuscripts; they are not used here for emphasis.)

So, to summarise, the jelly is made from a meat or fish bouillon which is heavily spiced. The meat or fish, to be served inside the jelly, is cooked in this bouillon and then set aside whilst the bouillon is further boiled, skimmed and strained until clear. Finally, the meat or fish is arranged in dishes and the bouillon is poured over. The whole thing is left to go cold and allowed to set.

In his commentary on this recipe, Terence Scully, the editor and translator of the Old French text, makes a very helpful observation about jelly that goes some way to explaining how galentine sauces were first devised:

Jelly was an important culinary confection, functioning as both a practical preservative for meats and a sort of presentation sauce for cold dishes. More perhaps than in other preparations, cooks developed their own preferences in the matter of the ingredients composing jellies as well as of the methods by which dependable jellies could be made. The foremost consideration in the composition of a good jelly – apart, of course, from the ready availability of animal gelatin among the ingredients entering into it – was the variety of spices chosen.

Scully, The Viandier of Taillevant, pp. 128-9. My own emphasis.

We learn a few things here: that medieval French cookery preserved fish or meat in jelly; that such jelly could be used more like a sauce; and that the spices that went into jelly recipes were important and varied significantly.

On jelly as ‘a sort of presentation sauce’, we only have to think about the way the firm but wobbly jellied stock, referred to above, becomes more of a gelatinous gloop as it becomes warmer.

Let’s develop this idea a little more by taking a look at the next-but-one recipe that appears in the Viandier, that is, ‘Lamproie a la galentine’: yes, those eel-like fish in galentine, again!

70. Lamproie a la galentine: Lamprey in Galantine. Bleed a lamprey as previously, keeping the blood, then set it to cook in vinegar and wine and a little water; and when it is cooked, set it to cool on a cloth; steep burnt toast in your bouillon, strain it, and boil it with the blood, stirring to keep it from burning; when it is well boiled, pour it into a mortar or a clean wooden bowl and keep stirring until is has cooled; then grind ginger, cassia buds, cloves, grains of paradise, nutmegs and long pepper and infuse this in your bouillon and put it, and your fish with it, in a bowl as was said; and put it in either a wooden or pewter vessel, and you will have good gelatine.

Scully, The Viandier of Taillevent, p. 288.

Scully emphasises in his commentary that this dish is actually served cold: as we read, both the lamprey and the bouillon are cooled. In addition, the bouillon, or broth, is actually coloured by the lamprey’s blood and thickened by toasted bread to create what Scully calls ‘the cold black galantine in which the lamprey will be served’ (p. 134). So: eel-like creatures in black gloop: mmm, bon apetit!

According to the recipe instuctions, it seems to me two choices are being offered: 1. the serving of ‘Lamproie a la galentine’ as a bowl of cold lampreys with a cold galentine sauce; and 2. if the bouillon is put into ‘either a wooden or pewter vessel’, a set galentine – a jelly.

Note how Scully makes a similar point:

A previous recipe, §68 has presented a general-purpose jelly for the serving and preserving of fish[.] […]

A plate en galentine could be eaten immediately after its preparation, or this sauce could be depended upon – as the gelee de poisson – to act as a preservative when the fish was meant to be eaten later.

Scully, The Viandier of Taillevent, p. 133.

We should note that Scully has translated the final Old French word of the recipe, ‘galentine’, as ‘gelatine’ (another way of spelling ‘gelatin’) rather than ‘galentine’. I wouldn’t call this an error but rather it underscores how closely related the original French galentine sauce was to the gelatinous broth from which it was made.

So what about the English galentines?

The strong association between galentine and gelatin brings me back to the recipe Gynggaudy (yes, that lovely green fish offal dish) in Forme of Cury. Remember its method states to add ‘a mixture of bread and galentine’ to wine and broth in order to make the sauce. It seems quite likely that the cook is being instructed to add a pre-made, set jelly to the mix.

This is also probably the meaning in another Forme of Cury recipe I haven’t yet mentioned, Sauce Madame, which is served with roasted goose. In this recipe, the instruction is given to ‘tak galentyne & grece & do in a possenet’, which might be best translated as ‘take jelly [or, gelatin] and fat and add to a possenet’.

Though the original French sense of ‘galentine’ is a jellied sauce, served cold, in the English recipes of Forme of Cury there is no clear evidence that any of the galentines were served as cold, jellied sauces. In fact, on the contrary, Fylettes in galentyne (no. 115) states that it should be served hot: ‘lete hit boyle a littul, and þenne serue hit forth’, ‘let it boil a little and then serve it forth’.

There are recipes in Forme of Cury that could be recognised as a jellied dish of preserved fish or meat – those using ‘gelee’ (‘jelly’) in their name – but it seems that by the time Richard II’s cookery book was being written, a decade or so after Charles V of France had popped his clogs, galentine was being used more broadly as a name for a spicy, somewhat acidic, broth-based sauce, thickened with bread.

Uncooked galentine

But what about recipe 136, Forme of Cury‘s uncooked Galentyne condiment/sauce mentioned at the outset?

Well, the only thing I can say here is that the English were following the French again. The Viandier also offers an uncooked, cold spicy ‘sauce’ that has nothing to do with jelly or gelatin.

For the dish ‘Lux’, the freshwater fish pike is cooked in water and ‘eaten with Green Sauce, or in a galantine made like good Cameline Sauce’ (p. 291; my own emphasis). So how is ‘Cameline Sauce’ made?

155. Cameline: To Make Cameline Sauce. Grind ginger, a great deal of cinnamon, cloves, grains of paradise, mace and, if you wish, long pepper; strain bread that has been moistened in vinegar, strain everything together and salt as necessary.

Scully, The Viandier of Taillevent, p. 295.

So to make a galentine ‘like a good Cameline sauce’ is essentially the way Forme of Cury describes the making of galentine; there is really not much difference between English Galentyne and French Cameline: both are vinegar-and-bread-based sauces, loaded with spices and strained for a smooth texture.

The English recipe for Cameline, found in Richard II’s cookbook, also uses the same basic method, though it uses different spices from the French recipe and does throw in nuts and currants for good measure!

Final thoughts

I think all of the foregoing underscores something I’ve said before, that French medieval cuisine influenced English cookery of the period, which is hardly surprising in view of the Norman Conquest. This influence is most evident perhaps in the frequent adopting of French names for English recipes.

But what this piece of research also shows is that English cooks, like their French counterparts, were happy to change things up a bit and move away from former traditions if they felt like it. Whether that meant heating up a formerly cold sauce or playing around with different spices and textures, so be it.

One thing that didn’t seem to change, however, was the habit of naming dishes in as confusing a manner as possible for modern day food historians! I mean, why would you give two very different sauces the same name? Remember that question the next time you’re making Galentyne.

Tip the author

If you like what you’ve just read, you may wish to “tip” the author, Dr Christopher Monk. Christopher is a freelancer who welcomes donations to his independent research and scholarship. If you prefer to donate using paypal.me, his link is paypal.me/drcjmonk. If you don’t use PayPal, you can use the donation box below to pay by credit card. Thank you!

$2.00

Make a one-time donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

If you enjoyed this blog post, please consider making a one-time donation to show your appreciation. All donations support my independent research.

Thank you,

Christopher

OMG. I would definitely have starved to death if I had lived in this era. Or maybe only if I’d had the misfortune to be of noble birth. I’d probably have been fine as a peasant…….. The fishy one really got me….

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know! I was thinking of you as I wrote this.

LikeLike

LOL!! ❤

LikeLike

Having worked on the Concordance of English Recipes, I can report that it’s not that uncommon a recipe by any means.

There are 34 recipes total in the galentine section in the Concordance. For a paper on

the topic of galentines see “Of Pike and Pork) Wallowing in Galentine” by C.B. Hieatt and Jane Terry Nutter which appeared in the 1997 Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you. That will be useful. What I would like to know is what led to the uncooked, non-gelatin sauce/condiment being given the same name as the broth- or bouillon-based sauces. I guess I’m trying to get inside the mind of 14th-century cooks. I appreciate your feedback. I need to get hold of a copy of the concordance. Is it still in print?

LikeLike

Looks like MRTS have dropped Hieatt’s volumes. It’s available on the OP market. Look around as prices will vary. I’ve seen it priced as high as four figures and this is while it was still in print. You might want to make an effort to grab the rest of her volumes before they are marked OS/OP. She died ten years ago, so the publishers will be removing her books.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. I’ve seen it for about £70; was hoping to get it cheaper than that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brilliant! I do NOT fancy the sound of the green fish guts one, though.

I know I’ve said it before but your research and the way you’re able to present so much information in such a clear and engaging way is something I really admire. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you. 😊 I really appreciate your comments.

Green fish guts! 😂

LikeLiked by 2 people

I second that on both counts!

LikeLiked by 3 people