Image: Detail from a bestiary of a woman milking a cow, who is licking its calf. Calves’ brains were an ingredient in a 15th-century recipe called Cenellis. Screenshot capture, British Library, MS Harley 4751, folio 23r (southern England, possibly Salisbury, 2nd quarter of 13th century).

In my recent post Language of Cookery 9: From brawn to brains, I observed that English medieval recipes for brain were rare. The only example I had found was a fifteenth-century recipe that wasn’t even a faithful brain recipe, but rather one that had altered an earlier recipe from Richard II’s Fourme of Cury (c.1390): from a dish containing ‘carnel’ or ‘flesh’ of pork into one containing ‘cervel’ or ‘brain’ of pork.

I had though missed something! I had failed to spot another brain dish when I was checking through the Concordance of English Recipes: Thirteenth through Fifteenth Centuries by the late Constance B. Hieatt. This is the dish known as ‘Cenellis’ (Hieatt 2006, p. 17), which is found in a collection of culinary recipes that has been dated to about 1490, a hundred years later than Fourme of Cury.

I searched out the text for this recipe: it wasn’t available as a digitised manuscript, but it had been edited by Hieatt (Hieatt 1996, p. 62, recipe no. 57). It seems clear that this is a dish containing brains. Here is the recipe in the original language, followed by my translation:

Cenellis. Recipe braynes of calvis heds or piges heds & put it in a pan or in a pott; & put þerto raw eggs & peper, saferon & vinegre, & stir it wele tyl it be thyk, & serof it forth.

Brains. Take brains of calves’ heads or pigs’ heads and put in a pan or in a pot; and put to this raw eggs and pepper, saffron and vinegar, and stir it well until it becomes thick, and serve it forth.

Middle English text from Hieatt 1996, p. 62; translation my own.

The title of the dish, Cenellis, is probably a corruption of the plural form of Old French cervel, meaning ‘brain’. Many medieval recipe names are notoriously difficult to pin down, some even scrambled beyond recognition, so there’s no real surprise here that the recipe name doesn’t make proper sense.

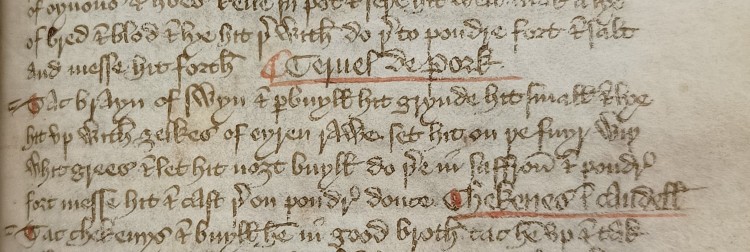

The method of the recipe is not that of the brain recipe mentioned above, Cervel de pork, which I previously checked on a trip to the British Library. Let’s just take a look at that recipe in order to compare the two:

Cervel de pork. Tak brayn of swyn & perbuylle hit; grynde hit smalle & lye hit vp with ȝelkes of eyren rawe; set hit on þe fuyr wiþ whyt grece & let hit noȝt buylle; do þereinn saffron & poudre fort; messe hit & cast þeron poudre douce.

Brain of pork. Take brain of swine and parboil it; grind it small and mix it up with raw egg yolks; set it on the fire with white fat [lard] and don’t let it boil; put into it saffron and powder fort; dish it up and cast upon it powder douce.

Edited by me directly from the manuscript, British Library, Junius D. viii, folio 92+ (image below; this is my own image and is shown with permission of the British Library; translation is also my own.

It’s important to remind ourselves that this recipe, possibly dating to the first half of the 15th century, is an alteration of the original late-14th-century recipe, which didn’t instruct the cook to use ‘brayn’ (brain) but rather ‘braun’ (brawn), meaning muscle meat; and, moreover, it was called ‘Carnel of pork’, i.e. ‘Flesh of pork’, not ‘Cervel de pork’, which is Old French for ‘Brain of pork’. Nevertheless, this recipe may represent a culinary shift, a desire to cook with and consume pork brain.

The recipe named Cenellis is not, however, a version of Cervel de pork, even if there are similarities between the two. Not only does the cook have the choice to use either calves’ or pigs’ brain but the brains are not first parboiled and ground in a mortar; neither are they fried in lard. Whole raw eggs are used, not just the yolks, and vinegar is added. Finally, the spicery is limited to pepper and saffron; there is no use of the spice mixes known as powder fort and powder douce. So, in effect, we have in Cenellis a “new” brain recipe.

Though I haven’t experimented with these two fifteenth-century brain recipes, I have given some thought to what the dishes would end up as if the methods were followed to the letter.

I fear Cervel de pork would end up as a bit of a mess. I’m fine with gently boiling the brain for a short while, and then frying it, perhaps cut into pieces; but grinding it, that’s just overkill, and sounds like the soft creamy texture of the brain would be ruined. This, I suggest, underscores the fact that this was not originally a brain dish, but rather a quite pleasant dish of spiced fried pork (I have actually cooked the original Carnel of pork, but that’s for another time).

Cenellis, on the other hand, sounds somewhat like the modern brain and scrambled egg combo, Brains and Eggs (or vice versa), that you might still find in rural kitchens of some US states (check this out); and it is akin to the Portuguese dish Omolete de Mioleira (‘brain omelette’); and I am sure there are variants of this dish from elsewhere in the world, so please leave a reply if you know of any.

Just to add, I think that in the medieval recipe the inclusion of vinegar would give a welcome piquancy to what might otherwise be quite a rich, eggy dish. I would try it. Especially if someone who knew what they were doing cooked it for me!

It’s good to find a genuine English medieval brain dish, one that seems to have been a brain recipe from the start. It still doesn’t move us away from the position in my previous post, that brains were not common fare in the Middle Ages, at least not in elite English households, the cuisine of which is represented by the recipe books I’ve examined. But we can perhaps suggest that at least by the end of the fifteenth century, brains had found their way onto some English tables and were not simply food for the dogs.

If you would like to support my independent research, please check out my Buy Me a Coffee page.

Bibliography

Hieatt 1996. Constance B. Hieatt, ‘The Middle English Culinary Recipes in MS Harley 5401: An Addition and Commentary’, Medium Ævum, Vol. 65, No. 1 (1996), pp. 54-71.

Hieatt 2006. Constance B. Hieatt and Terry Nutter with Johnna H. Holloway, Concordance of English Recipes: Thirteenth through Fifteenth Centuries (Tempe, Arizona: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2006).

Might “carnel” have been misread to “cervel” by a scribe? In 1963, the University of

Tucumán, Argentina, served our group of American Spanish teachers a dish of “sesos con huevos revueltos” (brains with scrambled eggs). I “missed” the opportunity to try brains because I happened to know what “sesos” meant. The others didn’t!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it’s possible ‘cervel’ was a misreading of ‘carnel’ at some point. But ‘braun’ was also changed to ‘brayn’ in the Junius codex. There’s an attempt, I think, to adapt the original recipe to make it a brain recipe. But the Harley MS recipe seems to be a fresh creation, specifying unequivocally that brains from the head of either calves or pig’s be used. What we get, therefore, is a more considered recipe method, one that works, one that doesn’t obliterate the brain!

So are you any more likely to eat sessos today? 😆

LikeLike

Nope, no sesos for me. I did manage to trick my brain into eating riñones (kidneys) with a poached egg on top at a hotel in Lima. Not too bad, but other than ground heart being mixed 50/50 with hamburger for spaghetti sauce, and tripe in Campbell’s pepper pot soup, I’m too well-conditioned against organ meats.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My favourite offal is chicken liver. Cooked in sherry and butter. Divine.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Forgot about liver. Used to slice calves’ liver into bits about the size of my little finger. Lightly coated in wheat germ, fried in butter and served over butter-y noodles. The kids actually liked it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sounds good!

LikeLike

Sesos, sorry. It autocorrected this!

LikeLike

Sesos, sorry. It autocorrected this!

LikeLike

I would disagree re the recipes being distinct; in my view they are very similar. Yolks only is not significantly different than whole eggs, ‘grynding’ may not mean grinding in our sense but cutting very small. Regarding ‘brawn’ as muscle meat, again, it may not be. It may be brawn (or the ingredients of) as we still know it today, a headcheese made with pork hocks, feet, bones, even the head and eaten cold, gelled, as a terrine, usually with mustard.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment. I do like people to offer their thoughts, but I must disagree with you.

Grinden, the Middle English word, means to grind, and sources show that in the context of cooking this was something done in a mortar (think e.g. of spices), so we simply are not talking about cutting up small; see https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/middle-english-dictionary/dictionary/MED19487/track?counter=1&search_id=20681728.

There are other words used in culinary texts that mean to cut and sometimes recipes specify to cut or chop things small.

I would suggest it’s best to consult the Middle English Dictionary (online) for definitions of medieval words; it’s tempting to rely on what’s familiar from today, but sometimes medieval words are false friends, and the connection to modern cognate words is not what we expect.

You will see that ‘braun’ is not used in the sense that you describe.

Brawn, the traditional ‘headcheese’ dish, does not appear in sources until significantly after the medieval period.

See this excellent resource: http://www.foodsofengland.co.uk/brawn.htm

LikeLike