Recipe and brief history of a medieval apple purée dish

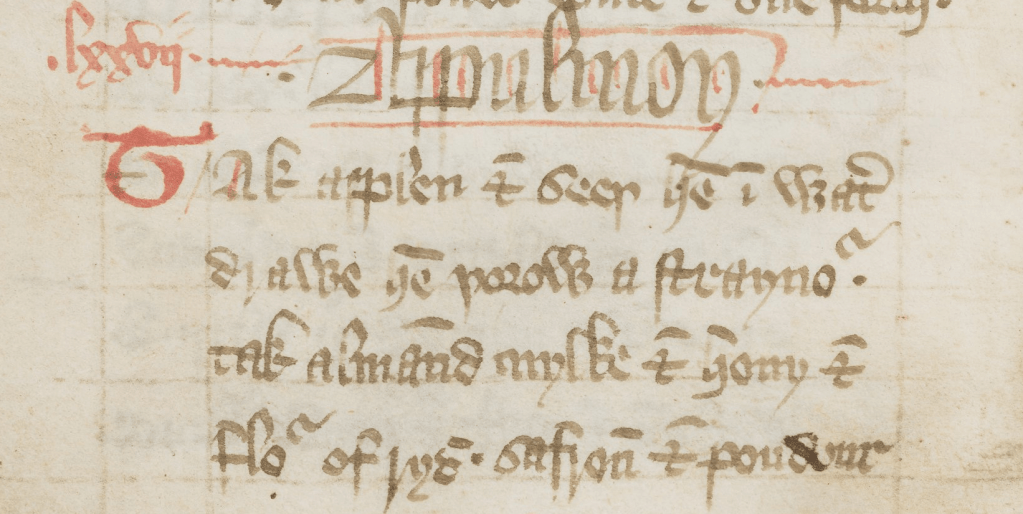

Appulmoy (77)

Tak applen & seeþ hem in water; drawe hem þorow a straynour; tak almaund mylke & hony & flour of rys, safroun & poudour fort & salt, & seeþ it stondyng.

Apple pottage

Take apples and simmer them in water; draw them through a strainer; take almond milk and honey and rice flour, saffron and powder fort and salt, and simmer it until very thick.

The recipe for ‘Appulmoy’ in Fourme of Cury. The Middle English text is from the manuscript, Manchester, John Rylands Library, English MS 7, folio 41v, and is edited and translated by Christopher Monk.

One authority has described Appulmoy as ‘applesauce’,[1] to which I have no choice but to invoke the Great British pantomime tradition and shout, “Oh no it isn’t!“. I’m only slightly exaggerating when I say that the only shared characteristic between the two is the use of the word apple.

On that point, the appul- of the dish’s name derives from Old English æppel, the word used by the Anglo-Saxons to mean ‘apple’ but also, more generally, ‘fruit, tree-fruit’.[2]

The instruction in Fourme of Cury, Richard II’s cookery treatise, to ‘seethe it standing’ (see the Middle English quotation above) makes it abundantly clear we’re not here talking about an apple sauce, that simple, sweetened apple purée that we might think of eating alongside roast pork.

If you’re missing the meaning here, I’ll explain: standing is not a reminder that the cook should remain vertical whilst at the stove (though this may be quite reasonable in view of it being the festive season), but rather that the Appulmoy should be thick enough to hold its own shape. And such standing thickness, we might call it, is due to the liberal use of rice flour in what turns out to be a rice pottage with a voluptuously creamy consistency – apologies for my Nigella moment there.

I am now going to get right to my modern-medieval version of Appulmoy before regaling you with more medieval food history and a sprinkling of joyous etymology. I promise it won’t be any more painful than Christmas Charades.

My recipe is based upon a single experiment conducted this week, so please feel free to modify as you see fit.

Appulmoy recipe

3 dessert apples

460 ml almond milk (recipe below)

150g rice flour

2 tablespoons honey, plus extra for drizzling

about 15 strands of saffron

½ teaspoon powder fort (recipe below)

pinch salt

whole almond kernels for decoration

My method

First grind your spices for the powder fort mix following the recipe below.

Then make up your almond milk according to the recipe below.

Grind, or crumble, the saffron and combine with a tablespoon or two of hot water to allow the colour to fully develop.

Peel your apples, remove the cores, and cut into slices. Place in a pan with just a little water and gently simmer until soft enough to pass through a sieve.

Press the cooked apple through a sieve into a bowl and leave to one side.

Confession! I actually didn’t cook my apples as I used slices of my own-grown apples (applause, please) that I had frozen. As I have learned, freezing apples changes their texture, making them soft enough to pass through a sieve without cooking. Freezing also seems to intensify the flavour.

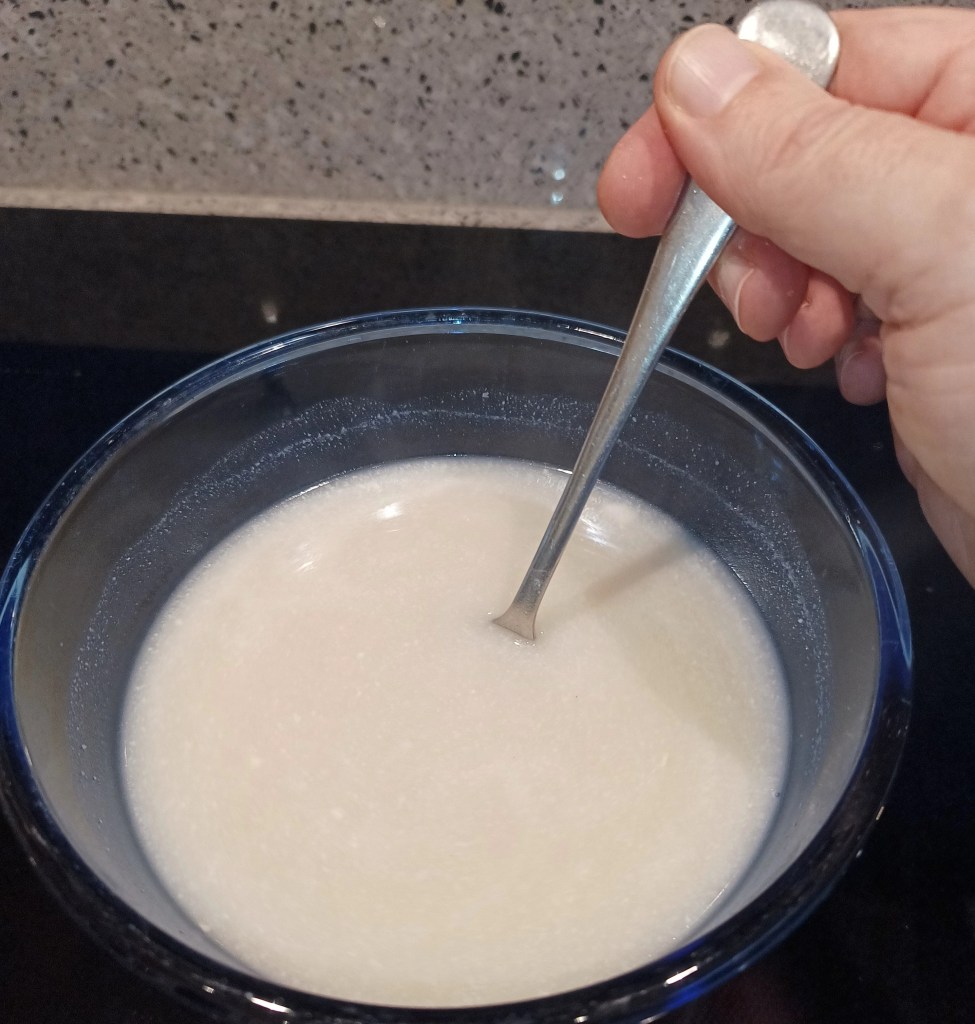

Next, pour your almond milk into a large saucepan and add the rice flour, combining the two.

Cook over a medium heat for about 8 to 10 minutes. Use a balloon whisk to keep the mixture moving as it thickens. The process of whisking will remove any lumps that initially form.

Once the mixture is smooth (about 2 minutes into the whisking) stir in the honey, powder fort, and salt.

And then finally add the saffron. Smile as your rice pottage takes on a golden hue from this magical ingredient.

Continue to cook until the rawness of the rice flour is cooked out – taste it to make sure.

Swirl the sieved apple through the pan of pottage – you don’t need to fully blend it in.

Serve it up in a bowl with drizzled honey and whole almonds as decoration. The almonds actually give it much needed texture.

To make my powder fort mix (aka specie negre e forte)

As there are no surviving English recipes for powder fort, I make up this peppery spice mix instead. It’s based on an authentic 14th-century Italian recipe, described as ‘specie negre e forte’, i.e. ‘black and strong spices’. Perfect!

Grind together as fine as possible the following in a pestle and mortar, or a spice/coffee grinder:

15g (½ oz) of black peppercorns

15g (½ oz) of long pepper

½ nutmeg (bash with your pestle to crack a whole nutmeg)

½ teaspoon of whole cloves.

To get the finest powder, sieve the mix through a fine-mesh sieve (a tea-strainer is a good improvisation), and keep re-grinding what doesn’t go through the first time until almost all of it does. I usually end up with a tablespoon or so of stubbornly coarse grindings which I just mix into the fine stuff.

Store in a jar in a cool place.

To make almond milk

This is a modified version of the almond milk recipe that appears in the 1976 book by Lorna J. Sass, To the King’s Taste; you might find a second-hand copy on AbeBooks or a similar site.

Pulverise 60g (about 1 US cup) of blanched almonds with a pestle and mortar, or grind in a food processor or other new-fangled device.

Dissolve 1 tablespoon of honey and a generous pinch of sea salt in 460ml (about 2 US cups) of boiling water, then add this to the almonds and stir well.

Allow the ground almonds to soak for at least 20-30 minutes, stirring occasionally.

Pass the mixture through a sieve to obtain a smooth milk (you can save the leftover almond pulp for mixing into your porridge).

The milk tends to separate but just give it a good stir before using.

More food history

Now, I hope you’re wondering how this dish was eaten in medieval England. As far as I understand, Appulmoy doesn’t actually appear on any of the surviving medieval feast menus. However, other rice flour-thickened pottages, often sweet, sometimes made using fruit, do seem typically to be served as a starchy foil for boiled or roasted meats and fowl, and sometimes fish.

The dishes Rosee (made with rose petals) and Moree (made with the colourant sanders to imitate the colour of black mulberries), which are both thickened with rice flour in Fourme of Cury, appear on the menu plans of a University of Durham manuscript of the early fifteenth century (Durham, University Library, MS Cosin V. iii. 11, folio 61r).

Rosee, ‘as pottage’, appears on a menu for ‘fish days’, served in the third course alongside sturgeon, welks, great eels and lampreys. Moree teams up with the thick starchy pottage Blandesyre (finely ground capon, or chicken, in a sweet rice and wheat starch pottage) to be served with swans, curlews, piglets, veal.[3]

It may be that Rosee and Moree were not served as thick as Appulmoy. Their recipes in Fourme of Cury don’t say they should be ‘standing’. There is, however, one other rice pottage that this was demanded of, and it is worth noticing how sweet it must have been.

The very sweet Vyaund Ryal appears in Fourme of Cury, King Richard’s cookery treatise, produced probably towards the end of his reign about 1390. It is a rice pottage with pine nuts, spices, Cyprus sugar, and black mulberries. It was made in the same basic way as Appulmoy, that is, rice flour and a liquid were boiled together until a thick consistency was achieved – ‘look that it be standing’, we are told. In this case the liquid used was expensive, sweet Greek white wine (or dry Rhenish white wine sweetened with honey) rather than almond milk.

This posh rice pottage appears on the feast menu for the coronation of Richard’s usurper, Henry IV, on the 13th October, 1399 – I reckon the scoundrel king nicked Richard’s cookery book, what say you, good people?! It was served as part of the first course alongside boar in pepper sauce; mutton, beef and pork – the three ‘Graund chare’ (‘great meats’) of the menu; and cygnet, capon, pheasant, and heron. Sturgeon was also part of the course.[4]

It must have gone down well with Henry since it reappears on the feast menu for his marriage to Joan of Navarre on the 7th February 1403, served alongside Fylettys in Galentyne, pieces of roasted leg pork further cooked in a thickened peppered broth, as well as the ‘great meats’ mentioned above, and cygnet, capon, and pheasant. It was also served as part of the first course of the ‘feast of fish’, suitable for monastic and secular clerics, which included salt fish, lampreys, pike, bream and roasted salmon.[5]

I’ve gone into all this food history to demonstrate, or suggest, that Appulmoy was probably also quite sweet and served alongside what we would today consider savoury fare. So, if you’re still planning your festive dinner (God help you), then maybe, just maybe, you might fancy reproducing your own Appulmoy for the Christmas table, giving it pride of place next to the cranberry sauce.

A history of Appulmoy and other apple purée dishes

Now, for you diehard nerds, a bit of history-cum-etymology of Appulmoy itself. I’m using Constance Hieatt’s Concordance of English Recipes as the basis for selecting the dishes below, all of which, wrongly or rightly, are included under the lemma Applemoys.[6]

14th century

Poumes Ammolee/Poumes Amole, meaning in Anglo-Norman ‘softened apples’. This is found in an early fourteenth-century Anglo-Norman recipe and in a slightly later Middle English translation thereof.[7] It is an early kind of sabayon, or egg custard made using wine, which is thickened with fine wheat flour. Diced apples are placed on top, along with sugar to ‘abate the strength of the wine’.

As you can see, this is nothing like Appulmoy – it’s possible the apples are cooked (the recipe is not explicit on this) but they are certainly not puréed. However, I included it because Hieatt lemmatises both the Anglo-Norman and English versions under Appelmoys, which I would suggest is a mistake. Indeed, curiously, Hieatt and Butler do not see them as the same dish, stating that they are not ‘closely related’.[8]

Appulmos, likely from Old English æppel + mōs, giving us ‘apple-food’.[9] Found in Diuersa servicia, no. 17, c.1381.[10] This is a fairly simple apple purée (apple sauce) made using sieved cooked apples and either beef broth and white fat (lard), or, on fish days, almond milk and olive oil. It is sweetened with sugar and saffron and ground spices are added.

Apulmose, likely from Old English æppel + mōs, giving us ‘apple-food’. Also found in Diuersa servicia, no. 35, c.1381,[11] this is a thickened variant of the above, using breadcrumbs as the thickener.

Pommys Morles, probably meaning ‘soft/softened apples’, the Anglo-Norman pommys meaning ‘apples’, and morles likely a corruption of the past participle of the Anglo-Norman verb moller, ‘to soften’.[12] The third apple dish of Diuersa servicia, no. 63, c. 1381,[13] this is a further derivation of the above two recipes, only this time ground-up rice rather than breadcrumbs is used to thicken the dish. Almond milk is the liquid used (no olive oil); broth is not given as an alternative. Finely diced apple, rather than puréed apple, is combined with the hot rice pottage. Sugar, saffron and spices are used as in the other dishes.

Appulmoy, probably a corrupted spelling of the earlier named Appulmos and Apulmose, though it is quite possible that the –moy element represents Anglo-Norman moil ‘wet, damp’,[14] and which in a culinary context may mean ‘softened’. This is the recipe found in Fourme of Cury, no. 77 in the John Rylands Library copy (text at the top of the blog post).

Similar to Apulmose, above, though rice flour rather than breadcrumbs is used to thicken it. It also resembles the previous dish, Pommys Morles, for it too uses only almond milk as the liquid. However, in Appulmoy, honey is used instead of sugar; salt is also added; and powder fort is specified rather than the vaguer ‘good powders’.

15th century

Appeluns for a Lorde, meaning ‘apples for a lord’. This is found in London, British Library, MS Arundel 334, c.1425.[15] A quite different dish from most of the above, though the apples are puréed and, similar to Poumes Ammolee, the first dish, a kind of custard is made using egg yolks.

So, the apples are cooked, ground and strained before being mixed with vernage, or other sweet wine, sugar, egg yolks, and rosewater. The dish is served thick in slices – ‘standing in slices in dishes’ – and finally strewn with apple blossoms.

Oddly, the method states, ‘This potage is in season April, May and June, while the trees blow’. This is somewhat confusing. Using the previous season’s stored apples as late as June would be remarkable, to put it mildly, and April and May, at least, are far too early to be finding ripe fruits on trees, though there may have been some early harvesting varieties of apples available in the early summer.

The reference to blowing winds in June may at a stretch suggest the use of fallen immature fruits during the so-called June drop, but by then there would be no apple blossoms with which to decorate the fruit.

All in all, this is rather confusing, and I must defer to those with greater knowledge of apple growing and storing – a call for help! What I can say is this is not Appulmoy, and therefore I suggest it shouldn’t have been listed in Hieatt’s Concordance under ‘Appelmoys’.

Pomesmoille, derived from Anglo-Norman, probably meaning in a culinary context ‘soft apples’; the pomes element meaning ‘apple’, the moille- element may derive from AN moil, ‘wet, damp’. This is found in Oxford, Bodleian Library, Laud MS 553, c.1430.[16] The method is almost identical to Pommys Morles (Ds, no. 63), above, i.e. it is made using rice flour.

Apple Moys, likely from Old English æppel + mōs, giving us ‘apple-food’. It is also found in Bodleian, Laud MS 553, c 1430.[17] It has the same method and ingredients as Appulmos (Ds, no. 17), above, i.e. it is the simple apple purée (apple sauce).

Apple Muse, again a derivation from the Old English æppel + mōs, giving us ‘apple-food’, seems likely. This is found in another British Library manuscript, Harley MS 279, c.1435.[18] This has elements of both Apulmose (Ds, no. 35), i.e. it uses bread crumbs (‘grated bread’) as the thickener, and Appulmoy (FoC), as it uses almond milk as the liquid (no broth or olive oil), honey as the sweetener, and a little salt. In addition, sanders is used as a colourant alongside saffron. Spices are not mentioned.

Apple Moyle, meaning ‘soft apples’, seemingly a mish-mash of English (OE æppel) and Anglo-Norman moil (see the comments for Pomesmoille, above). This is also found in Harley MS 279, c.1435.[19] Almost identical to Pommys Morles (Ds, no. 63), it too uses ground rice.

Appylmoes, likely from Old English æppel + mōs, giving us ‘apple-food’. This is found in British Library, Harley 5401, c.1490.[20] It is essentially the same as Apulmose (Ds 35), using grated bread as the thickener, and like Appulmos (Ds 17) it uses white fat (along with the broth) for flesh days. Rather than spice powders, ginger is specified as the spice.

Three further recipes of the Applemoys category are listed by Hieatt in her concordance, but they belong to a manuscript for which no reliable modern edition is available, so I have not investigated these.

Summary

When thinking about Appulmos, Apulmose and Pommys Morles of Diuersa servicia, the English collection produced probably just a few years (c.1381) before Fourme of Cury (c.1390), we see the progression from a thin apple purée sauce in the first recipe to a thickened apple purée in the second, followed by the introduction of rice flour as the thickener in the final dish. Appulmoy, the rice pottage of Fourme of Cury, is comparable to both the latter two dishes.

It seems very likely to me that the etymology of the names of Appulmos and Apulmose (and similar later English recipes) is from Old English æppel ‘apple’ and mōs ‘food, victuals, nourishment’, thus giving us the meaning of ‘apple-food’, and which may also hint at an earlier rendition of the dish in Anglo-Saxon England.

The spelling in Fourme of Cury, appulmoy, is either a corruption of the Old English of the above recipes, perhaps influenced by fourteenth-century Francophonic pronunciation of -mōs, or is a combination of Middle English appul (OE æppel) and a rendering of the sound of Anglo-Norman moil ‘wet’, a word which means in the context of cookery something like ‘soft’ or ‘moistened’. Thus appul + moy could be understood as ‘soft apple’ – or even ‘apple purée’.

If you’ve managed to get to the end, a hearty congratulations and an even heartier Merry Christmas!

Christopher

If you wish to support my work, you can “Buy Me A Coffee”

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Thank you! Your contribution to support my creative work and independent research is appreciated.

Donate[1] See Hieatt & Butler, p. 170, appyl.

[2] The Dictionary of Old English: A to I, æppel, 1 and 2: DOE: A to I (utoronto.ca) (limited free access available).

[3] Hieatt and Butler, p. 41.

[4] Austin, p. 57.

[5] Austin, pp. 58-9.

[6] Hieatt, Nutter, and Holloway, p. 4.

[7] Hieatt and Jones, pp. 867 and 878; and Hieatt and Butler, p. 46.

[8] Hieatt and Butler, p. 170, appyl.

[9] For mōs, see Bosworth-Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary online (bosworthtoller.com).

[10] Hieatt and Butler, p. 65.

[11] Hieatt and Butler, p. 69.

[12] See moller, moller 2 :: Anglo-Norman Dictionary.

[13] Hieatt and Butler, pp. 74-75.

[14] See moil :: Anglo-Norman Dictionary.

[15] The edited text, known as ‘Ancient Cookery’, is available here: https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=yGxBAQAAMAAJ&pg=GBS.RA2-PA472&hl=en [accessed 22 December 2023].

[16] Austin, p. 113.

[17] Austin, pp. 113-4.

[18] Austin, pp. 20-21.

[20] Austin, p. 30.

[20] Hieatt, p. 64, no. 76.

Select bibliography

Austin, Thomas (ed.). Two Fifteenth-Century Cookery-Books (published for the Early English Text Society by Trübner & Co., 1888).

Hieatt, Constance B. ‘The Middle English Culinary Recipes in MS Harley 5401: An Edition and Commentary’, Medium Ævum 65.1 (1996), pp. 54-71.

Hieatt, Constance B. and Sharon Butler (eds.). Curye on Inglysch: English Culinary Manuscripts of the Fourteenth Century (Including the Forme of Cury) (published for the Early English Text Society by Oxford University Press, 1985).

Hieatt, Constance B., and Robin F. Jones. ‘Two Anglo-Norman Culinary Collections Edited from British Library Manuscripts Additional 32085 and Royal 12.C.xii’, Speculum 61.4 (1986), pp. 859-882.

Hieatt, Constance B., Terry Nutter, with Johnna H. Holloway. Concordance of English Recipes: Thirteenth through Fifteenth Centuries (Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2006).

Fantastic work there Christopher! That Appulmoy looks particularly delicious. I think I’ll be giving that a go in the new year.

Quick question – I’m really not keen on cloves, so is there anything else I could substitute for them in the powder fort?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Darren. Cloves can be over-powering, though they work in the background in this spice mix. I would suggest either leaving them out or opting for a spice combo of your choice. You probably noticed how one of the fifteenth-century recipes used just ginger, and others simply had ‘good powders’. I like the pepper kick of my powder fort in what is essentially a sweet dish, but you may prefer ‘sweet’ spice such as cinnamon or cassia. Or even just a little grated nutmeg by itself would work well.

LikeLike

Lovely, thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It sounds halfway to a dessert to me. Sadly, it’s unlikey to go with our meat-free Christmas dinner, but I think it might go with the veggie sausages I use.

Merry Christmas

LikeLike

It’s definitely dessert-like to our modern taste buds. I actually enjoyed eating it best over the next few days after making it. Eaten chilled from the fridge (its texture goes smoother) and dipping chocolate oat biscuits into it! 🤣 Not very medieval!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is 2am and I have stumbled upon via an SCA post. I find this very interesting however I have some unique questions I would very much like to ask in a less public forum as it involves recovering from a nearly fatal illness. (Not medical advice just procedural)

Cordially Raven

LikeLike

You’re very welcome to contact me via the Contact tab in the menu. I’m glad you found it interesting.

LikeLike