More medieval food in Manchester’s ancient woodland

(Image of Queenly Bread in Bailey’s Wood is by Hannah Priest)

If you missed part 1 of Down In the Woods, well, you’re just very naughty, since you missed the launch of my new recipe for BBQ Smoked & Spiced Chickpeas. Don’t worry, it’s still there.

This new dish is based on Chycches, a recipe in Fourme of Cury. That’s ‘How to cook’ in modern lingo, and it was Richard II’s cookery treatise, dated to the end of the fourteenth century, and located today in the John Rylands Library in Manchester. Yes, these are Medieval Manchester Chickpeas! I jest. Just a little.

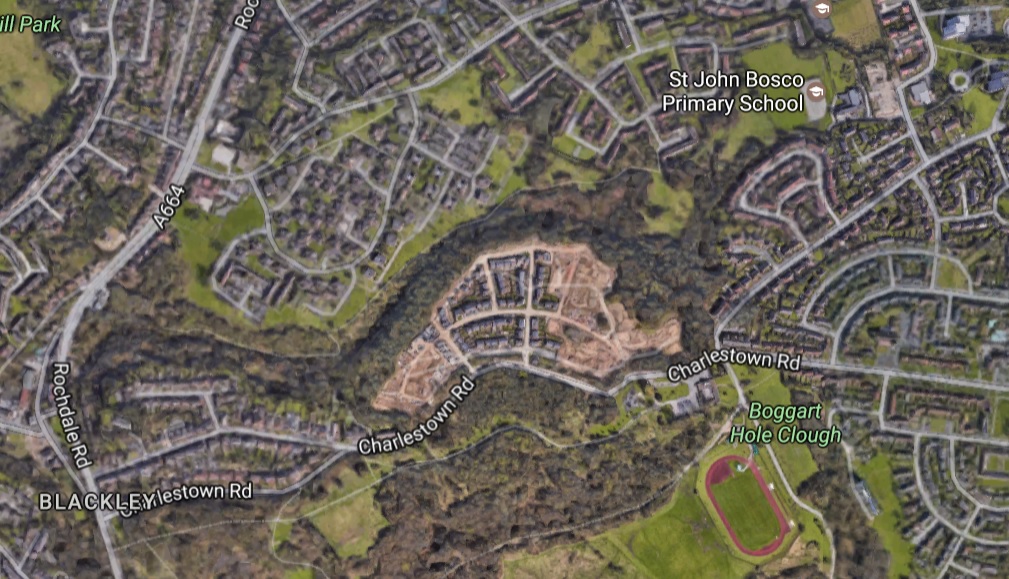

I have to say, they went down a treat with everyone at my Bailey’s Wood medieval food event. Bailey’s Wood, by the way, was once a medieval deer park, and is one of only a few areas of ancient woodland that have survived in the Manchester area, where I have lived for the last 23 years.

I promised in part 1 to give you two more recipes, and here they are, based, respectively, on recipes from Fourme of Cury, and an early fifteenth-century culinary collection found within a British Library manuscript.

Queenly Bread (Payne Ragoun)

Special equipment

Sugar thermometer (one with a clip)

Marble pastry board

Palette knife

Large heavy kitchen knife

Ingredients

200g honey (the runny stuff)

200g golden caster sugar (superfine)

200g pine nuts

2 teaspoon ginger powder

Cold water

Sheet or two of rice paper (I used a gluten-free one)

Method

Have ready a glass bowl of chilled water by the side of the stove; this is to test the readiness of the toffee mixture.

Place the honey and sugar into a pan on a medium heat. Attach the sugar thermometer to the side of the pan; it needs to be in contact with the mixture. As the sugar begins to dissolve into the honey, begin stirring steadily with a wooden spoon.

Continue to heat and stir until the mixture reaches 115°C (about 240°F). My thermometer calls this ‘soft ball’ stage. Once there, remove off the heat.

Take a small amount of the mixture with a teaspoon and drop it into the chilled water. Then with finger and thumb, press the mass together. It should come together easily and be malleable. This kind of water test is how it was done in the medieval period, as the Fourme of Cury recipe shows:

& whan hit hath yboyled a while tak vp a drope þerof with þy fynger & do hit in a litul water & loke yf it hong togider.

Literally, And when it has boiled a while take up a drop thereof with your finger and do it in a little water and look if it hangs together.

WARNING: Do not touch boiling toffee with your finger; the order of the original language is probably awry – or the experienced medieval cook may have put a tiny amount on a thumb or finger nail before plunging it into cold water! But do not try this either!

My ‘soft ball’ stage will give you an easy chew toffee. If you want it a little firmer, take the temperature to 125°C (about 260°F), or ‘hard ball’ stage. In the water test, the mixture will be slightly harder to press, but should still be malleable.

If you heat the mixture much higher than this you risk burning it; this is because honey can be less forgiving than sugar when heated at high temperatures. This is something alluded to in the original medieval recipe:

boyle it with esye fyre & kepe it wel fram brennyng.

Literally, boil it with easy fire and keep it well from burning.

Once you’re happy with the consistency, add the ginger powder, stirring it in well. Then add the pine nuts, mixing thoroughly. Allow the mixture to cool a little, just for a few minutes.

Splash enough cold water onto the marble board so that there is a layer of water on the surface. Then spoon out your pine nut toffee mixture onto the marble board. The water helps to prevent sticking. And this is the medieval way of doing it:

and cast it on a wete table.

(I think you can work this one out.)

The mixture may initially want to spread out, but as it continues to cool it will become firmer and hold its form better – this is particularly true if you’ve heated the mixture to the ‘hard ball’ stage.

Pushing and pressing firmly with the palette knife, shape the toffee into a rectangle or square, to about 2½ cm (1 inch) thick. Wetting the knife with water is a good idea, as it discourages sticking.

Here’s a video from two years ago showing me doing this shaping work (with a smaller amount of the toffee mixture, admittedly):

Then wet your heavy kitchen knife and cut the toffee into pieces. It’s up to you how many, but it is a very sweet dish, so maybe 12-16 pieces. Place these onto a sheet (or two) of rice paper, spacing them out to allow for any slight spread as they further cool and set.

Finally, cut the rice paper around the pieces of Queenly Bread. This leaves each piece with a base of rice paper and makes them easier to eat. If you want to be ultra neat, you can trim the edges of the toffee/rice paper with scissors before serving. And then hide all the trimmings for later – that’s what I did.

These delicious morsels of gooey, chewy pine nut toffee were extremely expensive to make: ginger, sugar, and pine nuts, all imported, were very costly back in the fourteenth century. Probably only those dining at the high table with King Richard and his queen, Anne of Bohemia, would have indulged. The recipe indicates that they were served with ‘fried foods’, that is, in the third and final course, along with other dainties, such as apple fritters and creamy custard tarts (doucettes).

They are still today rather pricey to make, so I suggest reserving the may-I-have-another piece for only your very best friends. 😉

Royal Fig Potage Tarts (Potage Ryall)

The original medieval recipe is a two-in-one recipe. First a thick pottage of figs and Osey wine (from Portugal, a forerunner to Port) is made. This is divided into two. The first half is spiced with cinnamon (or cassia) and ginger, and vinegar and salt are added – curious, I know!

The second part is spiced the same, but sugar and currants (raisins of Corinth) are added. This sweeter pottage then becomes the filling for a most unusual pastry case, one made with cream, which I have blogged about before.

Here’s how I made the ones for Bailey’s Wood:

Pastry made with cream (gluten-free)

Ingredients

200g Doves ‘Freee’ gluten-free white bread flour. Please Note: This brand already has the all-important xanthan gum in the flour blend; if your brand doesn’t list xanthan gum in its ingredients, then add 1 level teaspoon of it. You can substitute the same weight of plain white wheat flour (all-purpose flour).

150ml (150g) double (heavy) cream

4 teaspoons icing sugar (confectioner’s sugar)

2 large egg yolks (40g)

1-2 extra teaspoons of cream if needed; this is more likely if using wheat flour.

Method

Sieve the flour (and xanthan gum) and icing sugar into a mixing bowl.

Make a well in the flour and add the egg yolks and cream. Combine the ingredients thoroughly with a spoon or cutlery knife, until clumps of dough form. If you feel the dough is a bit dry, add the extra cream.

Bring together the clumps with your hand to form a ball of dough. It will be quite soft.

Form the dough into a neat, flattened disc about 3cm (just over 1 inch) thick. Wrap in baking paper and chill for 30 minutes.

On a floured surface, roll out the dough quite thinly, to about ½ centimetre thick. Cut circles from the dough with a jam tart cutter and line a jam tart tray. Chill the tray for another 10-15 minutes.

Bake in the centre of a hot oven for about 10 minutes at 200°C (180°C Fan, 390°F, Gas Mark 6). Take out the pastry cases and leave to cool on a cooling rack before filling.

Royal Fig Pottage filling

Ingredients

350g dried figs

30g of currants (raisins of Corinth, Zante currants)

100ml of sweet pudding wine (something like a Moscatel de Valencia, a Sauterne, or even a Botrytis wine)

¼ to ½ level teaspoon ground cinnamon

¼ to ½ level teaspoon ground ginger

Small pinch of clove powder, optional

Sea salt, optional

Method

Chop the figs into very small pieces. Place them into a food processor along with the currants and wine. Blend for a good minute or two until the mixture is very soft. Add extra wine if stiff.

Please note: for the event at Bailey’s Wood, I boiled off the alcohol from the wine in a pan, just in case any kids came along.

Then add your spices to the mixture and blend for ten seconds or so. Start with ¼ teaspoon each of the cinnamon and ginger, then add the rest if it suits your taste. Be careful with the clove powder; you want a tiny amount; too much will make it taste medicinal.

Fill the pastry cases with the fig pottage and smooth it over.

Place the sea salt into a small dish and offer your guests the option to add a flake or two to their tart – I’d suggest no more than that, even though the original recipe implies you ‘strew’ salt over them.

Royal Fig Pottage Tarts go great with a very modern cuppa – tea or coffee – or, for the more indulgent ones among you, some of the sweet pudding wine you put in the filling.

If you would like to support my independent research and creative work, please feel free to make a one-time donation.

Or, become a monthly subscriber.

The figgy tarts look fun, but I doubt my fillings would stand up to the toffee (or any other toffee).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha ha! I actually made them softer this time, so that when the audience tested them they didn’t need jaws of a Pitbull. But they are still super chewy. The fig tarts, I don’t know if you remember, I originally did with modern shortcrust pastry as Xmas canapes, but I decided to go back to the original recipe and use the cream-based ‘puff bread’ pastry. I think this combo really works. Hope you have a go. The pastry is really easy to work with.

LikeLiked by 1 person