Featured image: London, British Library, Lautrell Psalter, Additional 42130, folio 207v, detail

Hello modern-medieval food lovers.

As I’ve recently been researching the use of the Middle English word sauce, I was intending to post for this month a couple of new sauce recipes. There is perhaps still time, but I have to admit that life has got in the way – as it tends to do, doesn’t it?

I won’t bore you with all the details, but there are some ongoing health issues which I will update everyone with when the time seems right. And, moreover, we are putting our house on the market in order to move closer to my family. A mixture of feebleness and busyness is therefore my excuse! Please forgive me.

What I will leave you with are the original recipes for the two sauces I wanted to recreate for you. These are from the English medieval collection known as Fourme of Cury, compiled for King Richard II (r. 1377-1399) by his master cooks.

They are pretty easy to follow, though typically we have to work out for ourselves what the ratio of ingredients should be. So, with a little experimentation, I imagine at least some of you would like to recreate these for yourselves.

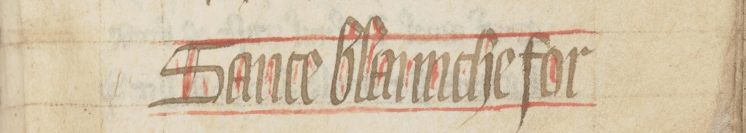

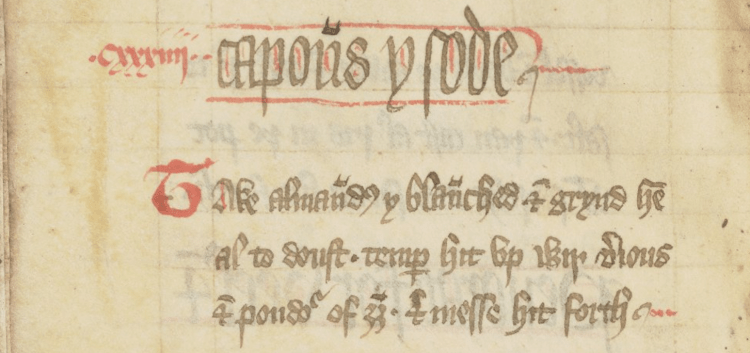

Sauce blaunche for capouns ysode

Take almaundes yblaunched & grynd hem al to doust, temper hit vp wiþ verious & poudour of gynger & messe hit forth.

White sauce for poached capons

Take blanched almonds and grind them all to dust; temper it up with verjuice and ginger powder and serve it forth.

My own edition and translation of the recipe from the John Rylands Library copy of Fourme of Cury (c.1390), MS English 7, folio 66r-v

This sounds like an exciting combination of warmth from ginger and pleasant acidity from verjuice, which is the unfermented juice from pressed, unripe grapes – or crab apples – quite widely available these days.

I love the rather melodramatic grynd hem al to doust in this recipe. It’s almost poetic. The meaning is clear, of course, that the blanched almonds need to be ground in the mortar as finely as possible. I may indeed use my own pestle and mortar when I do this, or I may ‘cheat’ and give way to the wonders of modern processing machines.

I’d recommend substituting chicken for capon, either a whole one or portions. Legs or thighs are good choices. You might fry rather than poach these, if you prefer.

Of note is that the sauce bears comparison with Jance de gingembre, found in a contemporary Middle French collection. This too uses almonds, ginger and verjuice – with the option to add white wine. Its method requires the sauce to be boiled.[1]

It is unclear if our Fourme of Cury sauce was meant to be boiled, too. Perhaps the cook – or attendant scribe – had been on the Malmsey and had forgotten to point this out. However, to be fair, there are plenty of sauces in medieval collections that are not cooked through. And though I think this sauce would benefit from some judicious simmering, I think it’s possible to get away without putting it on the stove.

Sobre sauce

Take raysouns, grynde hem with crustes of brede & drawe hit vp with wyne; do þerto gode powdours.

Sober sauce

Take raisins, grind them with bread crusts and mix with wine; add to this good powders.

My own edition and translation of the recipe from the John Rylands Library copy of Fourme of Cury (c.1390), MS English 7, folio 64r.

This sauce is ‘sober’ because it was suitable for Christian days of fasting, or ‘fish days’, as they were also known.

We should note that a later copy of Fourme of Cury has an expanded method that assists us in developing it further. Following on from ‘good powders’, it directs that salt be added and that the sauce should be simmered. It also, rather helpfully, instructs the cook to ‘fry roach, loach, sole, or other good fish; pour the sauce over and serve it forth.’[2] So, it is indeed a sauce for fish.

On the matter of the ‘good powders’, another later copy of the Fourme of Cury specifies ginger, cinnamon, sanders (a common medieval red food colourant) and sugar.[3]

When I get around to developing my own recipe for this, I will try both red and white wines, experiment with various spices, and make it up with and without a pinch of sugar – the sauce is already sweet from the raisins, so I’m doubtful it really needs any more sweetness.

I’m keen to see which of the fish I tend to cook with most – salmon, cod, haddock – may prove to be the best foil.

I’ll be leaving next week for a holiday in the Florida sunshine, and I hope to do a bit of culinary experimentation whilst I’m out there. So stay tuned.

If you would like to support my work or just say thank you, head on over to the Yieldeth Me a Cup of Mead tab, or consider becoming a monthly subscriber.

If you missed my video on sauces from a few years ago, or want to refresh your memory, here it is: Hot n Spicy Medieval Sauces. I remember it being one of the videos I most enjoyed producing.

Check out my YouTube channel for more videos.

[1] See The Viandier of Taillevent, ed. & trans. by Terence Scully (University of Ottawa Press, 1988), pp. 229 and 296, no. 168.

[2] See Constance B. Hieatt & Sharon Butler (eds.), Curye on Inglysch: English Culinary Manuscripts of the Fourteenth Century (Including the Forme of Cury), EETS SS 8 (Oxford University Press, 1985), p. 128, no. 134.

[3] See Hieatt & Butler, p. 128, no. 134, note for line 2.

Have a good holiday.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I will try 😉☺️.

LikeLike