In memory of Isobel Gairns (Ray’s mum), 18 November 1937 to 31 October 2024.

Mortrews

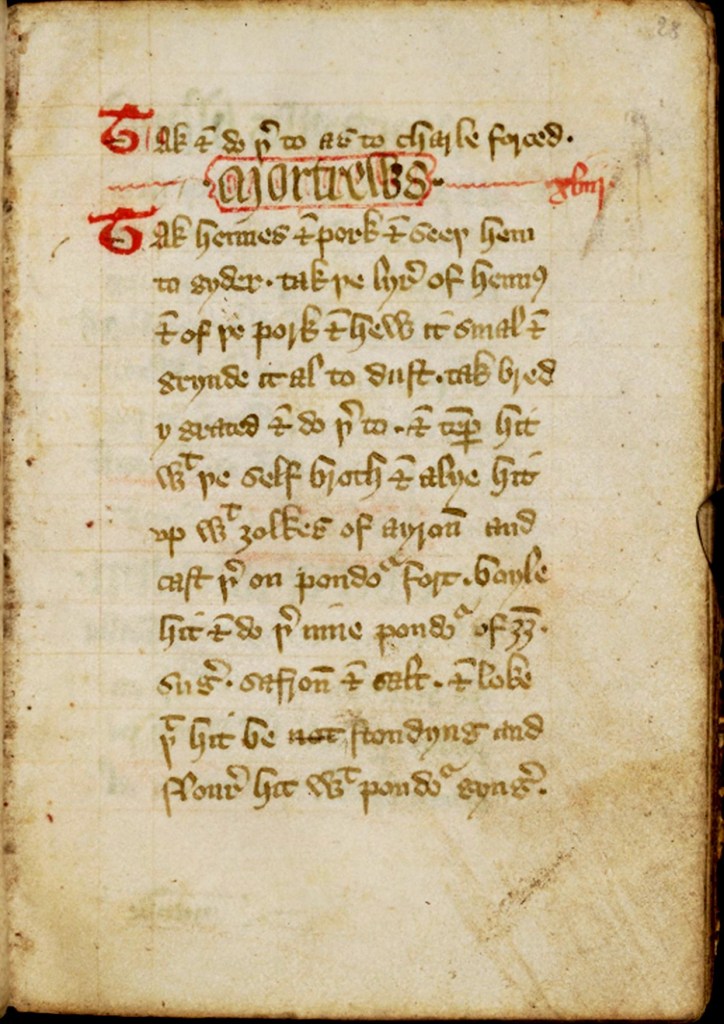

Tak hennes & pork & seeþ hem togyder, tak þe lyre of hennes & of þe pork & hew it smal & grynde it al to dust, take bred ygrated & do þerto, & temper hit with þe self broth & alye hit vp with ȝolkes of ayroun and cast þeron poudour fort, boyle hit & do þerinne poudour of gynger, suger, safroun & salt, & loke þat hit be stondyng and floure hit with poudour gynger.

Take hens and pork and simmer them together; take the meat from the hens and the pork and chop it finely and grind it all to dust; take grated bread and add thereto, and temper it with the same broth, and mix it up with egg yolks, and cast into this powder fort; boil it and add to this powder of ginger, sugar, saffron and salt; and make sure it is thick, and sprinkle it with ginger powder.

(Edited from the manuscript and translated by Christopher Monk)

The recipe above is from the John Rylands Library’s Fourme of Cury, the cookery book compiled for the household of Richard II of England (r. 1377-99) by his master cooks.

The dish Mortrews, spelt Mortrelles elsewhere in the manuscript,[1] was what we might call today a comfort food. Its finely ground pork and chicken (the dish’s name points to the grinding being done in a mortar), its flavoursome broth, spicing and seasoning, its enrichment with egg yolks, and thickening with breadcrumbs must have created a welcoming dish on a wintry day.

Somewhat stodgy, some might argue, but, then, who can deny the appeal of easy-to-eat, tasty, meaty starchiness when the skies have turned grey and the wind is icy? I certainly can’t.

Below, you’ll find my Modern|Medieval recreation of the dish, which you can adapt to your own taste. Experiment a little! Follow the basics, by all means, but play around with the spices, or be naughty and add grated cheese.

Before we get to the recipe, however, here’s a brief history – a sampling – of mortrews recipes from medieval collections. The variations are intriguing.

Comforting an upset tummy

There is some evidence that in England, at least, this dish, or some form of it, was used to feed those recovering from an upset stomach. A recipe from a twelfth-century collection of Anglo-Norman medical recipes prescribes a decoction of wheat bran as the basis for making a mortrels, which is to be given ‘al malade a manger’ (to the sick to eat) as a counter for cursun (diarrhoea).[2]

We won’t dwell on that for too long, but you get the idea that this dish was thought of as having nourishing, restorative qualities.

Wheat bran was steeped in water to make a decoction, which was then used as the broth for making mortrels (another name for mortrews).

From a twelfth-century Anglo-Norman medical recipe, England.

It is worth noting that several centuries later mortrews was still being used for invalids. The famous dictionary of Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) has an entry for Mo’rtress that cites the early modern scientist Francis Bacon (1561-1626) who evidently thought that such a dish, made with capon breast meat [brawn of capons], stamped and strained and mingled with almond butter, was excellent for nourishing the weak. Who’s going to argue with Bacon?

[Go to the entry at the Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary Online project].

French connections

Two major Middle French culinary collections have versions of mortrews. The first is from the well-known household guide Le Menagier de Paris, written probably by the aging knight Guy de Montigny for his beloved, youthful wife at the end of the fourteenth century.[3]

Mortereul (= mortrews/mortrelle), we are told, was made like another dish, Faux grenon which probably has the sense of ‘mock porridge’.[4] The latter has either chicken livers and gizzards – the muscly parts of a chicken’s stomach – or, alternatively, veal, pork or mutton, cooked in water and wine and then finely minced – which would be with knives, so not ground – and fried in bacon fat.

Ginger, cinnamon, cloves, grains of paradise are the chosen spicing for the dish. These are added to more wine, verjuice, and beef bouillon, as well as plenty of egg yolks. The minced meat is further cooked in this.

We are told that some people add saffron, ‘car il doit estre sur jaune couleur’ (for it must be of a yellow colour); and some add pain hazé (toasted bread), ground and sieved, in order to further thicken the dish – the egg yolks also serving this purpose. Finally, cinnamon powder was sprinkled atop of each tasty bowl.[5]

We can see how this Faux grenon closely resembles the Fourme of Cury’s Mortrews. Finely processed meat, good broth, egg yolks, spices, bread, and the colouring with saffron are common to both.

The author of Le Menagier informs us that Mortereul is made the same way, ‘sauf tant que la char est broyee ou mortier avec espices de canelle’ (except that the meat is ground in a mortar with cinnamon). However, there is no bread for further thickening. So this was a thinner version of mortrews.

As we have seen, King Richard’s master cook was having none of this. Though he may have been influenced by Parisian tradition, he was having bread in his dish to give it some body. Look out that it be stondyng (literally, standing thick) was his call. Thick it would be, and he was still going to call it by its Anglicised French name.

Just a little palaeographical aside. You will notice that in the Rylands Library manuscript, above, there is a scribal correction: the word not, just before stondyng has been crossed through. This, for me, when we take it as a whole, underscores the emphasis the recipe places on good old comforting thick stodge.

We don’t truly know if the original scribe realised his mistake, and corrected it, or if a later scribe took action. And I would not discount the possibility that the master cook who provided the recipe, or even another cook who was later using it, saw the error and objected, “Of course Mortrews is thick! Correct this at once!” Maybe I’m a tad melodramatic, there.

The other medieval French collection to have a version of mortrews is the slightly less well-known cookery treatise by Master Chiquart,[6] who served for some time at the beginning of the fifteenth century as the chief cook to Count Amadeus VIII, subsequently Duke Amadeus I, of Savoy. Chiquart presents this dish to his would-be well-trained cook – the imagined reader – as one of his supplemental dishes should a planned two-day feast turn into something longer. Oh, the thought of running out of food to serve!

Calling it le chaut mengier partir, that is ‘the party hot dish’ (i.e. party as in partitioned, or divided, as we will see), but observing that is ‘also called Morterieulx’(= mortrews, mortrels), Chiquart gives such a detailed recipe that it is worth recounting his steps in full,[7] should you wish to replicate it:

- Get plenty of pork meat, clean it, wash it thoroughly and set it to cook (boil over the coals), putting in salt.

- When done, remove it onto ‘good clean workbenches’, removing the skin and bones, and then la haches tresbien minut, ‘hack it up very small’.

- Take good bread and soak it in beef bouillon, adding to this spices, namely white ginger, grains of paradise, pepper – ‘not too much’ – and saffron to give it colour.

- Then having also added verjuice and white wine to this, strain it all, and put the resulting thickened bouillon into a good pot over hot coals.

- Brown the pork in ‘good white pork fat’ in a clean pan – ‘fry it good and nicely’ – and when fried add in a little of the bouillon mix.

- For the next step, I’ll give you the full translation (by Terence Scully): ‘Then get enough eggs for the amount there is of the pottage and strain the yolks into it through a filter cloth in order to bind it.’

We are then told that when the time comes to take it to the dressing table, in order to serve it up, there should also be there ‘a big dish full of powdered cinnamon with a lot of beaten sugar in it’. Once the Morterieulx is put into its serving dish,[8] half of it should be covered with the cinnamon-sugar powder, the other half is to be left un-spiced – ‘that way it will be “party”’.

It does seem that spicing varies in mortrews recipes quite significantly, according to the medieval cook’s tastes perhaps, or that of their lord or lady. As I intimated earlier, when recreating the dish ourselves, we shouldn’t feel constrained, but choose spices to suit our own and our co-eaters’ palate.

Something fishy

Of the variants of mortrews dishes, fish versions seem to have been rather popular. At least fifteen recipes have survived from the medieval period.[9] Here’s one of the clearest, Morterews of fysch, found in a manuscript right at the end of the medieval period, in the last quarter of the fifteenth century. Though its provenance is unknown, the manuscript has been associated with Norfolk, because of the text’s dialect.[10]

Here’s the translation by Constance Hieatt:[11]

Take blanched almonds; make milk of them with water boiled with sugar and salt. Take codling, thornback,* or haddock, and boil it with water and salt. When it is boiled, pick it clean from the bones and the skin, then grind it small. Mix it with the [almond] milk and put it in a pot. Then grate wastel bread and add that to it so that it will be very thick, and stir it together well. Colour it with saffron. Slice it into dishes. Make a garnish of ground ginger and cinnamon, and put on top.

And if there is liver, grind it with the fish.

*ray

This apparently sliceable version of mortrews appears to have been created for Lent, when no meat, dairy produce or eggs could be eaten. The characteristics of the meat version are still there, however: the flesh of both is ground finely, spices and saffron are used, and the dish is thickened with bread. Wastel bread, if you don’t already know, was a fine quality white bread.

My own version

Even as I look to medieval methods, as far as they are discernible, I am also, always, influenced by modern techniques of preparation and cooking; thus my version exploits both worlds. I have most definitely used the Fourme of Cury version, the recipe at the beginning, as the foundation, but I have chosen to poach the meat gently with the spices, rather than add them all after the initial cooking of the meat, as the original recipe implies was done. The differences in the resulting tastes are perhaps quite subtle, however.

I also chose to add a little garlic in the broth, as well as a piece of fresh ginger – probably unavailable in medieval England – in addition to dried ginger. It’s my choice, and I would always advocate making your own choices when adapting medieval recipes for your own table. Adapting was in fact what medieval cooks did themselves, so in a sense we are simply following their lead.

I certainly will repeat this dish – it was incredibly tasty – but I may well tweak it here and there. I might, for example, sprinkle it with ginger ground into a powder perhaps with a little white sugar, or do so with a cinnamon-sugar powder, as some of the medieval recipes suggest. If you do have a go at my recipe, please do let me know how you get on.

The recipe

(Feeds two greedy very hungry persons)

You will need a food processor – or a big mortar and pestle in which you don’t mind grinding meat.

Ingredients

250g belly pork, thick strips

2 chicken legs

2 soft white bread rolls (I used gluten free ones), blitzed into breadcrumbs using the food processor

4 large egg yolks

A generous pinch of saffron strands (approx. 20), steeped in a little hot water

½ teaspoon powder fort spice powder, plus a little for sprinkling

1 Knorr chicken stock pot (or 1 teaspoon of chicken bouillon concentrate)

For the poaching broth:

1 litre water, boiled from the kettle (I used 1½ litres which was more than I needed)

2 teaspoons dark unrefined sugar (dark Muscovado would be good; I actually used what the Brits call molasses sugar)

1 teaspoon sea salt

Several pieces of cassia bark (as the bark often gets broken during processing and packaging, the pieces vary in size, but enough to cover your palm is about right)

1 teaspoon black pepper corns, lightly crushed in a mortar

1 teaspoon long pepper, lightly crushed in a mortar (I was using a small variety of long pepper, but if you have the bigger variety, use about three pieces)

1 piece of fresh ginger, about 8-10cm (3-4 inches), thickly sliced

1 piece of dried ginger, about 5cm (2 inches), bashed in a mortar

2 garlic cloves

Method

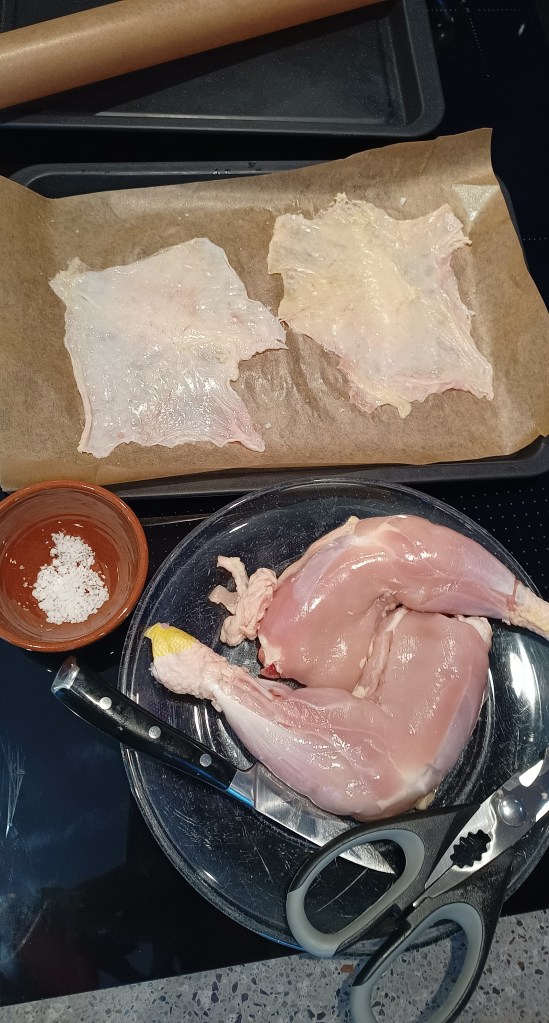

Note: As I decided to make crispy chicken skin for a modern twist, I first skinned the chicken legs. You don’t have to do this. And getting the skin to crisp isn’t as easy as TV chefs make out! If you do want to do this, I advise preparing your skin ahead of time. More on this at the end of the post.

Make up the poaching broth by pouring the boiled water into a large saucepan and dissolving the sugar and salt. Next, add the fresh ginger, garlic, and the poaching broth spices, but don’t add either the saffron or powder fort, as these are for later.

First, poach the pork belly strips. The pork takes longer to cook than the chicken, so it goes in earlier. Bring the pan to boiling point, then reduce the heat to low so that you have a very gentle simmer. Cover with a lid. If you have a glass-lidded pan, it’s easier to keep an eye on it so that it doesn’t boil rapidly. This is a gentle poaching.

After 30 minutes, add the chicken legs. This will cool the broth somewhat, so bring it back to the required simmering – a few bubbles at the sides – and cook for a further 30 minutes or until the chicken is just done and no more. Further cooking takes place, so don’t go for dropping-off-the-bone tenderness.

Once there, remove the meat from the pan. Reserve one piece of the belly pork, keeping it warm wrapped in foil. Allow the rest of the pork and chicken to cool enough so that you can handle it. Then pull off the chicken meat from the bones, making sure not to get any gristle. Place this and the remaining belly pork, roughly cut up, into your food processor (or large mortar). Blitz (or grind) the meat until it resembles sausage meat, so quite finely ground.

Strain your poaching broth into a bowl and wipe your pan clean. To the pan add 250mls (just over half a US pint) of the strained broth, and dissolve into this the chicken bouillon concentrate, and also add the half teaspoon of powder fort spice mix.

Please don’t throw the remaining broth away; it’s too good! I reduced the volume of mine by rapid boiling, cooled it, and then froze it.

Beat the egg yolks with a fork and add the saffron liquid to them. Take a little of the broth from the bowl (not from the broth in the pan) and temper with the yolks. You do this by beating or whisking in about 3 tablespoons of the broth, one tablespoon at a time.

Put your ground-up meat into the pan and stir it into the broth. With the pan off the heat, gradually add the tempered egg yolks, stirring them in, and then add the breadcrumbs. It’s best not to add the breadcrumbs all at once, as you need to decide how thick you want your Mortrews. I ended up using three quarters of them. You may want it truly stondyng and so use them all.

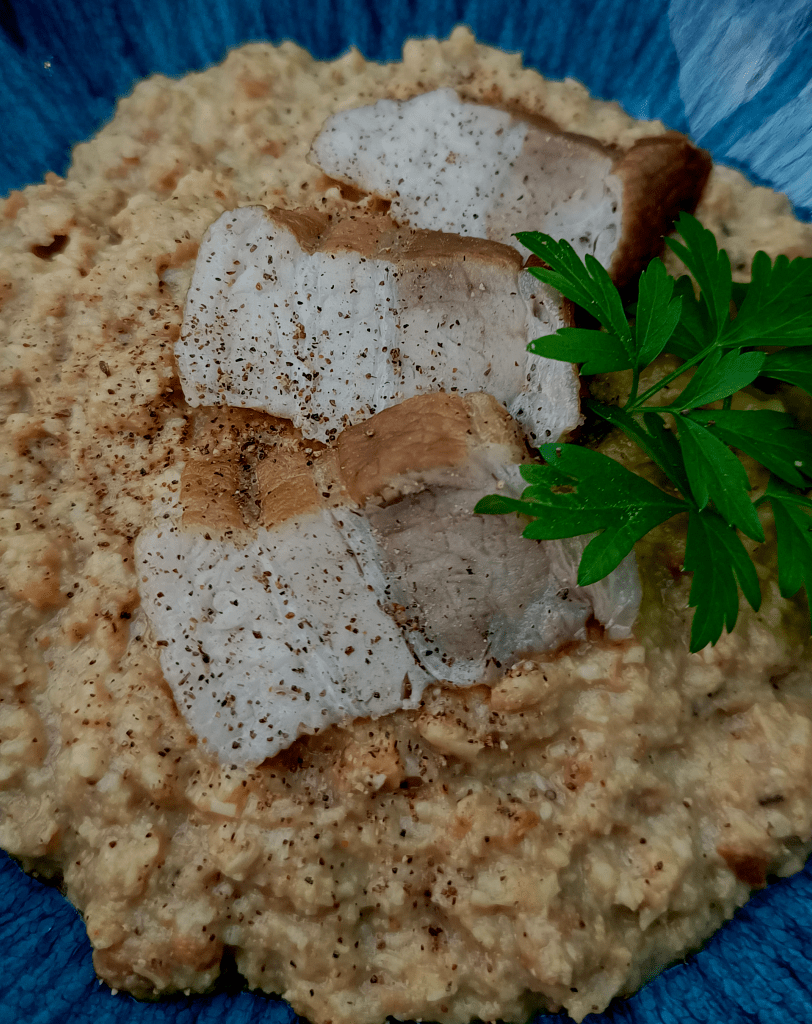

Return the pan to the heat – keeping the temperature low – and cook the whole for about 7 or 8 minutes. Keep stirring and do not boil the Mortrews. You should notice that the mixture becomes quite creamy, almost custardy, like a thick silky risotto. It is the egg yolks, as they cook, that makes this happen.

Serve up your Mortrews in warmed bowls. Slice at an angle the reserved piece of belly pork so that you have a few slices to place atop of each bowlful. A little parsley as garnish adds some needed colour.

Finally, sprinkle over a little more powder fort spice.

If you would like to support my independent research and recipe development that lies behind this website, please consider a small donation by heading to the Buy Me a Coffee page. Or you may be interested in becoming a regular monthly subscriber, in which case head over to the Subscribers page. Thank you!

Crispy chicken skin

If you want to add crispy chicken skin to your Mortrews, which does give a great texture to the dish, then go for it, but make sure you have enough time to do this. Here’s what I did – too late, as it happens – as I attempted conscientiously to follow the modern, classic chef’s method.

I took care to remove the skins from both legs in order to keep them as whole pieces. My tip is to cut around the top of the bone with a sharp knife, then from the plump end cup up towards the top of the bone with scissors. Then gently peel away the skin, pushing your fingers underneath it as you go. If it gets a little stuck, you may need to use the scissors or knife to ease it from the flesh.

Next I seasoned both sides of each skin with a little sea salt, and placed them onto a piece of greaseproof paper, lining a baking sheet. Then I smoothed the skins out so that there were no wrinkles. Then I covered the skins with another sheet of the paper, and placed another baking sheet on top to weight the skins down.

This then went into the top of a moderately hot oven (180°C Fan = 200°C/400°F) where it was supposed to crisp up within 15 minutes. It didn’t. And I can tell you, frankly, that this method never seems to work for me in my fan-assisted oven.

So, after 15 minutes, I removed the top baking sheet and piece of greaseproof paper, and allowed the skin to cook, uncovered, for another 10 minutes. Still not crisping, I switched off the oven, whilst harrumphing, and abandoned the skin to its fate. It worked! Though too late for the first helping of the Mortrews, I did have some of my best ever crispy chicken skin on my second helping!

Bibliography

Crossley-Holland, Nicole. Living and Dining in Medieval Paris: The Household of a Fourteenth-Century Knight (University of Wales Press, 1996).

Greco, Gina L. & Christine M. Rose (trans.). The Good Wife’s Guide (Le Ménagier de Paris): A Medieval Household Book (Cornell University Press, 2009), Kindle edition.

Hieatt, Constance B. (ed. & trans). Cocatrice and Lampray Hay: Late Fifteenth-Century Recipes from Corpus Christi College Oxford (Prospect Books, 2012).

Hieatt, Constance B. ‘Supplement to the Concordance of English Recipes: Thirteenth Through Fifteenth Centuries’, in Hieatt, Cocatrice and Lampray Hay, pp. 145-172.

Hieatt, Constance B., and Terry Nutter with Johnna H. Holloway, Concordance of English Recipes: Thirteenth through Fifteenth Centuries (Arizona Center for Medieval & Renaissance Studies, 2006).

Hunt, Tony. ‘Early Anglo-Norman Recipes in MS. London, B.L. Royal 12 C XIX’, Zeitschrift für französische Sprache und Literatur, Bd. 97, H. 3 (1987), pp. 246-254.

Le Menagier de Paris, ed. Georgine E. Brereton and Janet M. Ferrier (Clarendon Press, 1981).

Scully, Terence (ed. & trans.). Du fait de cuisine / On Cookery of Master Chiquart (1420) (Arizona Center for Medieval & Renaissance Studies, 2010).

[1] Mortrelles is the spelling in the table of contents for the dish that follows, Mortrews blank, which is very similar dish, but uses almond milk and rice flour.

[2] Hunt, p. 248.

[3] See Crossley-Holland, p. 8; Crossley-Holland discusses the authorship in more detail in her Appendix 1, on pp. 185-211.

[4] See Greco & Rose, p. 312, n. 59.

[5] Le Menagier, p. 246, no. 235; Greco & Rose, p. 312, no. 235.

[6] Chiquart’s Du fait de cuisine is edited and translated by Terence Scully; see Scully in the bibliography for details.

[7] See Scully, pp. 220-21.

[8] Oddly, Chiquart at this point switches the name to Faugrenon (a variant of Le Menagier’s Faus grenon), showing how close the two dishes were. Or perhaps it is evidence for a momentary lapse of concentration by Chiquart. See Scully, p. 221, note 52.5.

[9] See Hieatt et al, pp. 58-9, and Hieatt’s ‘Supplement’ in her Cocatrice and Lampray Hay, pp. 160-61.

[10] The manuscript is Corpus Christi College, Oxford MS F 291. It is edited by Constance Hieatt, under the title Cocatrice and Lampray Hay, the details for which are in the bibliography. For the Norfolk association, see Hieatt, Cocatrice, p. 10.

[11] Hieatt, Cocatrice, p. 66.

I’m genuinely sorry to hear about Ray’s mum, RIP.

On the more comforting subject, this really does sound like a fun dish. Who (except of course vegetarians) can resist finely ground spiced meat? The fish version actually sounds like a precursor to the fishpaste cakes you find everywhere in Japan (especially the swirly ones in ramen).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your kindness.

I like the connection you bring up about the fishcakes. Very interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Am curious why muscovado sugar was chosen rather than a higher quality of more refined sugar, especially since this dish was made for royalty.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a good query. In the first instance, I chose it for flavour; it works better as a broth enhancer. That was my modern cook’s mindset in operation. The other things to remember about Fourme of Cury is that it includes humbler dishes as well as the more ‘ingenious’ fare, as it’s put in the introduction. The collection as a whole would have catered for the royal household, which was very large, and not just the king’s table, so to speak. I hope that helps.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course sometimes you just want pure white sugar without any extra taste getting in the way of your sugar bomb, but usually I do prefer the molasses hint that turbinado / muscovado bring.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m with you there. Certain modern cakes — I’m thinking parkin, in particular — have to have darker sugars in them.

Also, from the medieval elite culinary context, it’s difficult to be certain that sugar always meant refined or white unless such was specified, which it sometimes was (e.g. Cyprus sugar). And as use of any type of sugar would have incurred significant cost, it’s fair to say, I’d suggest, that even recipes including unrefined sugars (a flan using dark sugar comes to mind) should be thought of as elite.

LikeLike

It’s a good query. In the first instance, I chose it for flavour; it works better as a broth enhancer. That was my modern cook’s mindset in operation. The other things to remember about Fourme of Cury is that it includes humbler dishes as well as the more ‘ingenious’ fare, as it’s put in the introduction. The collection as a whole would have catered for the royal household, which was very large, and not just the king’s table, so to speak. I hope that helps.

LikeLike