You all probably know the famous Christmas carol The Twelve Days of Christmas, which was first published towards the end of the eighteenth century.[1] Well, here, for a bit of festive humour (accompanied, it goes without saying, by sound historical research, cough, cough), I present an alternative medieval version for the final twelfth day.

The online facsimile of the 1780 version

On the twelfth day of medieval Christmas my true love sent to me twelve lords a-leaping… after receiving their food rents.

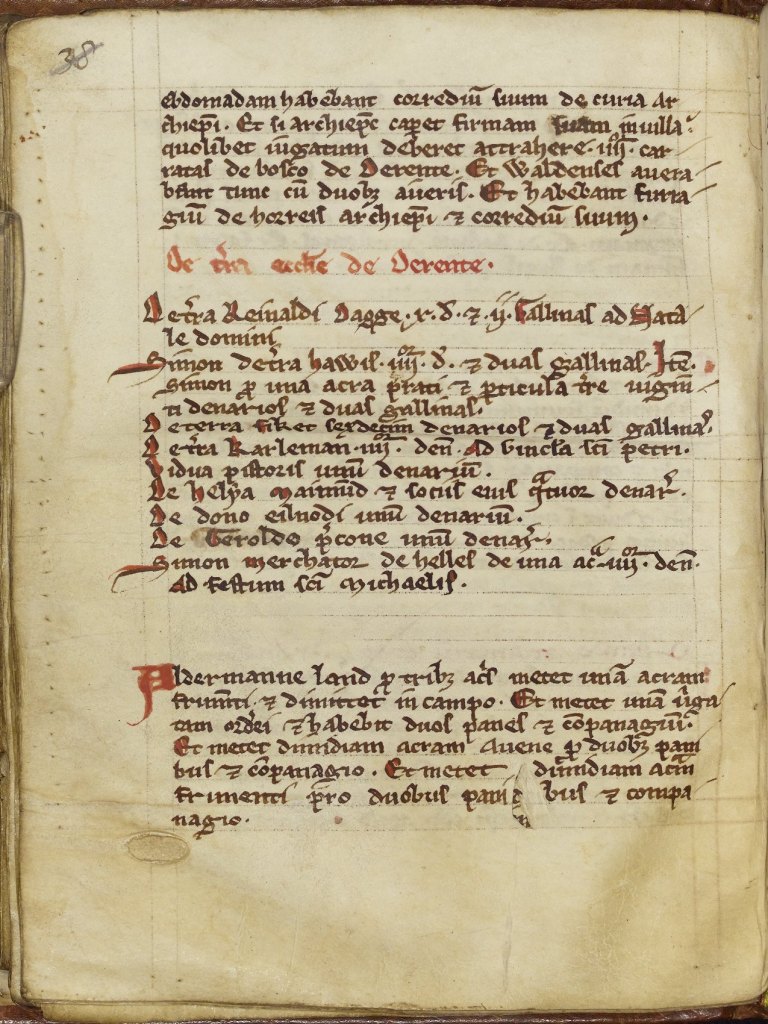

’10 pennies and 2 hens at Christmas’, lines 8 and 9 (translation) from a page of food rents in Custumale Roffense, folio 21v.

Dean & Chapter of Rochester Cathedral (with permission).

At Christmas, the various tenant farmers for Rochester Priory, of which the monks were the collective manorial lord, were required to present all sorts of food rents to their lord, according to their status.

Some examples of rents, recorded in the thirteenth century Rochester Custumal (sample above), include eights sheaves of oats; one market lamb, one sheep’s fleece, and one virgate of barley; 2 hens and ten pennies; 16 hens; and two capons, two loaves, and a pot of ale containing at least 2 gallons.

For some, food rents were commuted to money: ‘At Christmas as food-rent, 5 shillings and 3 pennies’ were expected from the Weald dwellers.

For an overview of thirteenth-century food rents for the monastic ‘lord’ of Rochester Priory, go to Food rents c. 1235 — Rochester Cathedral.

On the eleventh day of medieval Christmas my true love sent to me eleven ladies dancing… with their boxes of gingerbread.

‘[B]efore Christmas’, Eleanor de Montfort, Countess of Leicester and Pembroke, had delivered to her ‘one box of gingerbread’ – likely several pounds of ginger toffee confection – along with 60 pounds (in weight) of almonds, 6 pounds of ginger, 8 pounds of pepper, 6 pounds of cinnamon, 1 pound of saffron, 1 pound of cloves, 12 pounds of sugar, 6 pounds of blanche powder (finely ground ginger and sugar) with six shillings worth of mace.[2] A spicy Christmas, indeed!

On the tenth day of medieval Christmas my true love sent to me ten pipers piping… and…

On the ninth day of medieval Christmas my true love sent to me nine drummers drumming…

I have medled things, here, to borrow and repurpose a medieval culinary term; thus we have pipers and drummers together – or, rather, individual musicians playing both pipe and drum at the same time! Well, that’s a special Christmas gift, wouldn’t you say?

The thirteenth-century Cantigas de Santa María (Songs to the Virgin Mary) depicts two such fellows. To be precise, they play a pipe and tabor, which is a small drum. The Cantigas is a collection of manuscripts written in Galician-Portuguese, complete with music notation, authored during the reign of Alfonso X El Sabio (1221-1284).

On the eighth day of medieval Christmas my true love sent to me eight maids a-managing the production of butter and cheese.

At least by the thirteenth century, professional dairymaids, within the English manorial system of farming, carefully managed the production of cheese and butter, and this was audited by reeves or bailiffs appointed by the lord, as is indicated in three surviving agricultural treatises.[3]

In one of these, known as Husbandry, the importance of butter reaches a new level with the production requirement of as much as one stone of butter to every seven of cheese. Now that’s a sign that butter had become an expensive luxury, and profit was now the driving force behind its production.[4]

A woodcut of a dairymaid, 1491.

Ortus sanitatis. Public Domain Mark. Source:

Ortus sanitatis, Wellcome Library, Slide number 7658 and EPB Incunabula 5.e.13

On the seventh day of Christmas my true love sent to me seven swans a-swimming in the royal swanneries… and in a Chaudyn sauce.

A certain Ralf Soote, in the year 1391, was the ‘overseer and keeper’ of Richard II’s swanneries, where wild swans were semi-managed.[5] Soote was accountable for ‘all the king’s swans in the river Thames and elsewhere throughout the realm’.[6]

Swan as food appears just once in King Richard’s cookery book, Fourme of Cury (c. 1390), served with Chaudyn, a sauce made from the swan’s offal and blood:

Chaudyn for swannes

Take þe lyuour and þe offalle of þe swannes & do hit to seeþ in gode broth; take hit vp, take out þe bones, take and hewe þe flesche smale; make a lyour of crustes of brede & of þe blode of þe swan ysoden; & do þerto poudour of clowes & of peper & a litul wyne & salt & seeþ hit; & cast þe flesche þerto yhewed and messe hit forth with þe swan.

Take the liver and the offal of the swans and simmer it in good broth; remove, take out the bones, take and chop the meat finely; make a thickened sauce from bread crusts and the blood of the cooked swan; to this add powder of cloves and of pepper and a little wine and salt and simmer it; and cast into this the chopped flesh and serve it forth with the swan.

Edited from the John Rylands Library manuscript (English MS 7) and translated by Christopher Monk.

On the sixth day of Christmas my true love sent to me six geese a-laying… but not until February.

The goose of medieval Britain was a variety of greylag goose (Anser anser). There is evidence, as observed by the agricultural historian Philip Slavin, ‘that medieval greylag geese laid eggs at the beginning of February, and not in March or April as their modern descendants do.’[7] Medieval or modern, Christmas geese a-laying is artistic whimsy.

Goose eggs were highly valued. On average, according to late medieval records from eastern England, ‘goose egg prices were 5.5 times higher than hen ones’.[8] Whether their value was due to consumption or hatching is unclear, however; but Slavin notes, ‘there are occasional references to the dispatch of eggs to urban centres’,[9] which does suggest they ended up on the tables of townsfolk.

On the fifth day of medieval Christmas my true love sent to me five gold

ringsleaves.

Well, to be honest, a lot more than five, and silver leaves besides. What for? They were needed for decorating the Cokagrys, a gastronomic hybrid of stuffed cockerel and suckling pig, sown together, spit-roasted and basted with a saffron-and-egg-yolk glaze, and, for the ultimate statement of excess, gilded with gold and silver leaves. Though I have no proof that this dish was ever served at Christmas for Richard II – in whose cookery book it appears – it really should have been. Beats a goose any Christmas day!

It is a good possibility that the ‘foyles of gold & of syluer’ laid across this culinary masterpiece were bay leaves covered in edible gold and silver leaf. Bay, Laurus nobilis, was evidently cultivated in elite English gardens throughout the medieval period, appearing, for example, in the plant descriptions of the gardener and botanist Friar Henry Daniel who was a contemporary of King Richard.[10]

The name of the dish eventually morphed into forms of cockatrice, the vernacular English name for the feared basilisk, a hybrid serpent and cockerel (depicted on the left).

Image from the Rutland Psalter, folio 81r (London, British Library, Additional MS 62925). Were the golden leaves made to look like a serpent’s scales, I wonder?

On the fourth day of medieval Christmas my true love sent to me four coal-black birds…

Blackbirds are sometimes depicted in medieval manuscripts as caged birds, kept for their sweet song. Here is an image from northern France, 13-14th-century.

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS fr. 1269, folio 7r. Source.

Though this is debated, the original colly birds of the earliest eighteenth-century lyrics meant birds that were as black as coal, thus blackbirds – not, then, the four calling birds of my childhood memories.[11]

Certainly, the Old English word col does mean coal; and the phrase swa sweart swa col ‘as black as coal’ is found in an Anglo-Saxon medical text.[12] But a direct etymological link to the blackbird this is not. But hey, it’s Christmas, and the blackbird as colly bird suits my purpose, since blackbirds had a culinary use in medieval cuisine.

In one of the menus appearing in the late fourteenth-century Le Menagier de Paris, blackbirds (mesles) are specified for the second course of roasted meats, alongside capons, rabbits, partridges, plovers, small birds (oiseletz), and kid goats.[13] I promise, I am not feeding my local blackbirds with mealworms to fatten them for Christmas!

On the third day of medieval Christmas my true love sent to me three French hens… with a note to keep them away from peahen chicks.

A curious piece of medieval information about hens – in this case French hens – is passed on to his youthful bride by the aged French knight Guy de Montigny, the likely author of the aforementioned Le Menagier. He notes, concerning hens who have taken to brooding a peahen’s eggs alongside her own, that though the eggs all hatch together, ‘the baby peacocks do not survive for long because their beaks are too tender, and the hen does not seek delicate food for them as their nature requires’ – evidently spiders and caterpillars.[14] So, rufty tufty French hens back then!

I couldn’t find three French hens but how about these three Belgian hens – well, two hens and one cockerel – from a Belgium Book of Hours, c. 1475

Pierpont Morgan Library, MS M. 485, folio 40v via Wikimedia Commons.

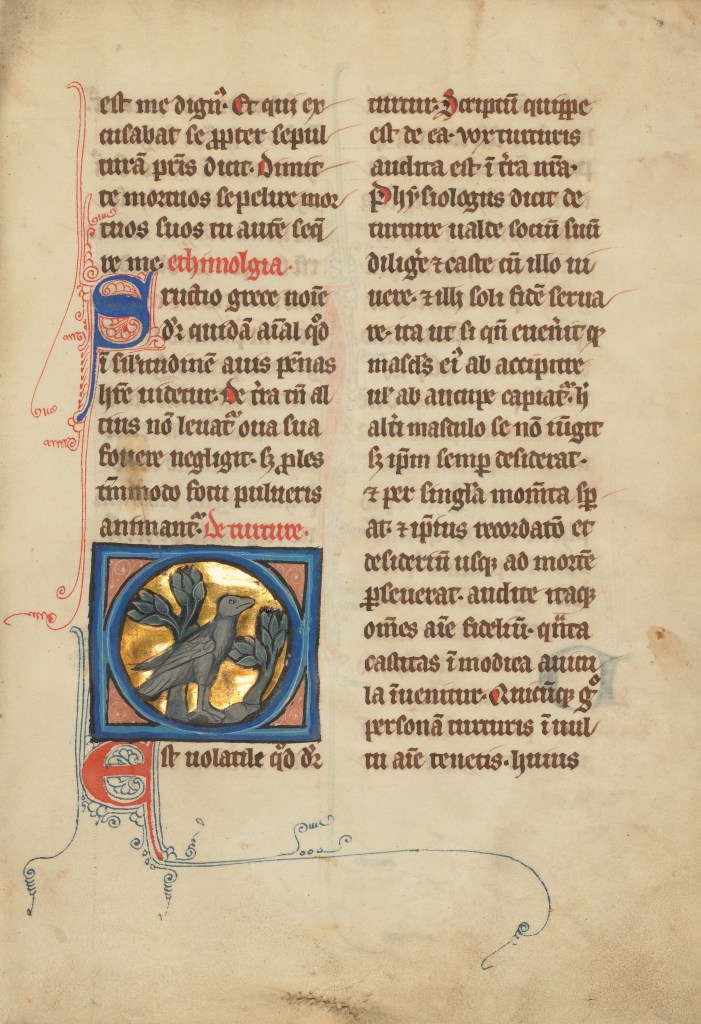

On the second day of medieval Christmas my true love sent to me two turtle doves that he’d caught on their autumnal migration to Sub-Saharan Africa.

It must be acknowledged, here, that I am assuming migration patterns were not so different in medieval England and Wales as they are today. Please do correct me if I’m wrong.

Turtle doves, those pretty little pigeons, with their purring turrr turrr turr cooing, breed in southern and eastern England and the lowlands of Wales, but migrate to their wintering grounds in Senegal. On the way, they pass through France (and other countries), where they face the real risk of being shot.[15]

The medieval French were intent on a similar interruption, shall we say. The aging French knight of Le Menagier, mentioned above, informed his bride that should she ever wish to breed captive turtle doves (or linnets and goldfinches), she would need to put carded wool and feathers into their cages.[16] How very thoughtful.

On the first day of medieval Christmas my true love sent to me a grey partridge in a warden pear tree.

If Christmastime in late medieval England is our time and place, then the native grey partridge, rather than the red-legged partridge, introduced in the 1700s,[17] would have been the pear tree’s occupant. The tree, of course, would have been bare, so to bring on any seasonal and fruitful joy, the true love would not have forgotten to send a basket of winter-stored pears, too.

The most common of the named pears at this time in England was the warden pear.[18] Historian Christopher Dyer observes that elite folk enjoyed eating pears at wintertime, especially at Christmas, and that wardens, along with St Rule and jonett pears were the most luxurious.[19]

However, to eat the warden, a cooking pear, a tasty recipe would be needed, and what better than Richard II’s Peerys in comfit, pears cooked in wine and served with a syrup spiced with ginger (link to my Modern|Medieval recipe).

And, finally, to maintain the culinary slant of these twelve days of medieval Christmas, I simply have to remind everyone wishing to cook partridge for Christmas that, as Richard’s master cook notes, you must must must parboil the partridge, and then interlard it with pork back fat to keep it moist on the spit. Oh, and don’t forget the ginger sauce! They really liked ginger, didn’t they?

‘Note well: peacock and partridge should be parboiled, larded and roasted, and eaten with ginger sauce.’

From Fourme of Cury, Manchester, John Rylands Library, English MS 7, folio 69r. Link.

If you wish to support my independent research and creative output, head over to either the Subscribers tab or the Buy Me A Coffee tab. Thank you!

Merry Christmas one and all!

Bibliography

‘Close Rolls, Richard II: February 1391’, in Calendar of Close Rolls, Richard II: Volume 4, 1389-1392, ed. H C Maxwell Lyte (London, 1922), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-close-rolls/ric2/vol4/pp322-324 [accessed 21 December 2024].

Crossley-Holland, Nicole. Living and Dining in Medieval Paris: The Household of a Fourteenth-Century Knight (University of Wales Press, 1996).

Dictionary of Old English: A to Le online, ed. Angus Cameron, Ashley Crandell Amos, Antonette diPaolo Healey et al. (Toronto: Dictionary of Old English Project, 2024).

Dyer, C. C. ‘Gardens and Garden Produce in the Later Middle Ages’, in Woolgar et al, pp. 27-40.

Greco, Gina L. & Christine M. Rose (trans.), The Good Wife’s Guide (Le Ménagier de Paris): A Medieval Household Book (Cornell University Press, 2009), Kindle edition.

Harvey, John. Mediaeval Gardens (B. T Batsford, Ltd, 1981).

Kindstedt, Paul S. Cheese and Culture: A History of Cheese and Its Place in Western Civilization (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2012), Kindle edition.

Le Menagier de Paris, ed. Georgine E. Brereton and Janet M. Ferrier (Clarendon Press, 1981).

Roberts, Margaret. The Original Warden Pear (Eventispress, revised 2018).

Sharp, Cecil J., A.G. Gilchrist & Lucy E. Broadwood. ‘Forfeit Songs; Cumulative Songs; Songs of Marvels and of Magical Animals’, Journal of the Folk-Song Society,vol. 5, no. 20 (November, 1916), pp. 277-296.

Slavin, Philip. ‘Goose Management and Rearing in Late Medieval Eastern England, c.1250-1400’, Agricultural History Review, vol. 58, no.1 (June 2010), pp. 1-29.

Stone, D. J. ‘The Consumption and Supply of Birds in Late Medieval England’, in Woolgar et al, pp. 148-61.

Wilkinson, Louise J. (ed. & trans.). The Household Roll of Eleanor de Montfort, Countess of Leicester and Pembroke, 1265 (The Boydell Press, 2020).

Woolgar, C. M., D. Serjeantson, & T. Waldron (ed.). Food in Medieval England: Diet and Nutrition (Oxford University Press, 2006).

[1] According to Wikipedia, the earliest known publication of the lyrics to the carol appeared in an illustrated children’s book Mirth Without Mischief, published in London in 1780 and in a broadsheet by Angus of Newcastle, dating to the late eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries. The order appearing on page 16 of Mirth Without Mischief is that followed here in this blog post.

[2] Wilkinson, p. 29, no. 12., p. 29, no. 12.)

[3] See Kindstedt, pp. 141-45.

[4] Kindstedt, p. 144.

[5] On the development of swanneries in late medieval England, see Stone, pp. 156-58.

[6] ‘Close Rolls, Richard II: February, 1391’, p. 323.

[7] Slavin, p. 15.

[8] Slavin, p. 8.

[9] Slavin, p. 8.

[10] See Harvey, p. 168.

[11] See Sharp et al, p. 280.

[12] Dictionary of Old English, col. 2.a.

[13] Le Menagier, p. 181.

[14] Greco & Rose, p. 332. On the authorship of Le Menagier de Paris, see Crossley-Holland, p. 7 and Apendix 1.

[15] For an overview of the turtle dove, go to https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/birds/pigeons-and-doves/turtle-dove.

[16] Greco & Rose, p. 332.

[17] For an overview of the grey partridge, go to https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/birds/grouse-partridges-pheasant-and-quail/grey-partridge. For the entry on the later, introduced red-legged partridge, go to https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/birds/grouse-partridges-pheasant-and-quail/red-legged-partridge.

[18] See Roberts.

[19] Dyer, p. 35.

I must say that I was saddened to reach the end of this blog. I wanted it to continue…on and on and on!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s really nice of you to say. But it did my brain in, writing it. Took far too long 😆. Merry Christmas x

LikeLike

Semi-managing is the best one can hope for, with swans…

Merry Christmas!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! Same with geese, really. And a very merry Christmas to you x

LikeLiked by 1 person

They have terrifying mouths, geese.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was fun 🙂

Merry Christmas to you both.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you enjoyed it. Merry Christmas, April x

LikeLiked by 1 person