The fires brenden vpon the auter brighte, That it gan al the temple for to lighte. Chaucer, The Knight’s Tale.

In this new series of short research pieces, I will be shedding a little scholarly light on ingredients from medieval cookery, with particular focus on Richard II’s late-fourteenth-century cookery book Fourme of Cury (‘method of cookery’).

Featured image information: Dairy maid milking a cow, from a medieval English bestiary (1226–1250). Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Bodl. 764, f. 41v. Photo: © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Previous post: heading cabbage

Young cheese

Young cheese – cheese that has not been aged for any significant time – is what is probably meant by tender chese in the recipe For to make flampens (a flampen is a type of pie) found in Richard II’s cookery book, Fourme of Cury (c.1390). It appears only once in this particular recipe collection.

As well as ‘young’, Middle English tender, in the context of recipe ingredients, may also have the sense of ‘soft enough to crush’.[1] To all intents and purposes, the cheese for the flampens recipe would have been soft because it was young; and, moreover, a relatively soft cheese was what was desired for the filling of this pie, as we shall see later.

Young cheese, was also known as fresh, new or green cheese – no, it was not green in colour, but green as in immature.[2] It would have had a high moisture content, and was made for quick consumption. Like other cheeses of the time, it was likely made in thin flat wheels.[3]

The method of its production had been around for centuries and is described in detail by Columella of Spain in his first-century farming treatise Re rustica (c. 60 AD).[4] It included the following:

- using animal rennet in fresh, warm milk for coagulation;

- ladling of the subsequent curds into a wicker basket or vessel;

- draining away any residual whey to allow the curds to mat together;

- gently pressing the matted curds;

- and, finally, rubbing the cheese in dry salt or putting it into a salt brine solution.

The Middle English poem Piers Plowman, written by William Langland in the 1370s or 1380s, helps us to make a distinction between curds and young, or green, cheeses. The eponymous subject is at one point in the poem facing hunger, and he points to his meagre rations, including ‘two green cheeses, a potful of whey and boiled curds’.[5]

Curds, whether coagulated with rennet or an acid, such as vinegar (which is how I make my own curds), were evidently eaten immediately, but a cheese proper, we might say, needed to be processed further – that is, pressed and salted.[6]

Sheep’s milk or cow’s milk cheeses?

Though nine of Fourme of Cury’s 194 recipes use cheese of some sort or other, only one specifies tender or young cheese. Would the young cheese have been a sheep’s milk or cow’s milk cheese?

Well, though none of the recipes specifies the animal from which the milk was taken, we need to bear in mind that in late medieval England there had been a significant shift from sheep’s milk to cow’s milk production by the fourteenth century. Cheese historian Paul Kindstedt observes:

During the thirteenth century the production of cheese began to be uncoupled from the production of wool, with cows increasingly being raised exclusively for milk production and sheep raised exclusively for wool. This was the beginning of a progressive shift from sheep to cow’s-milk cheese making on large demesnes, which resulted in the disappearance of most sheep’s-milk cheeses in England by the end of the fifteenth century. (Kindstedt, p. 143)

It is rather likely that by 1390, about the time when the tender cheese recipe and the other eight cheese-containing recipes were collated for Richard II, the cheeses available for the cooks were almost inevitably cow’s milk cheeses. It is unnecessary, though, for us to rule out a young sheep’s milk cheese.

The Fourme of Cury recipe

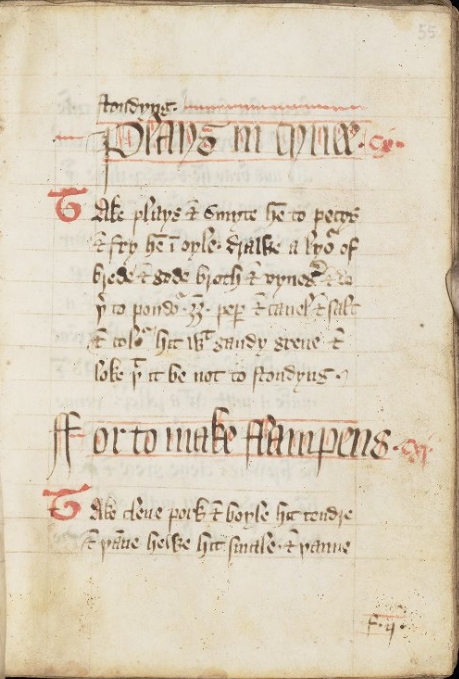

For to make flampens (111)

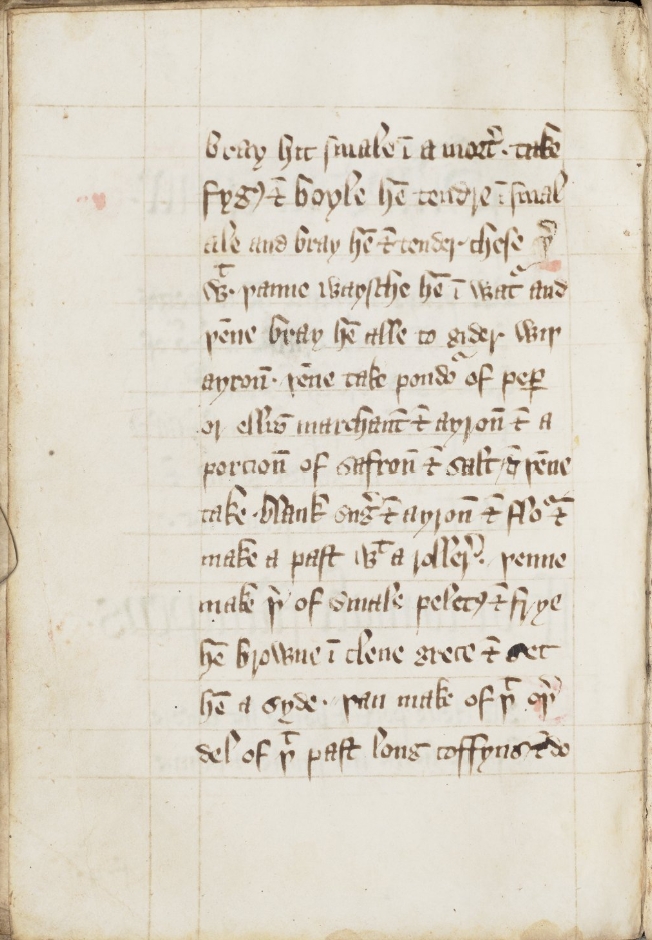

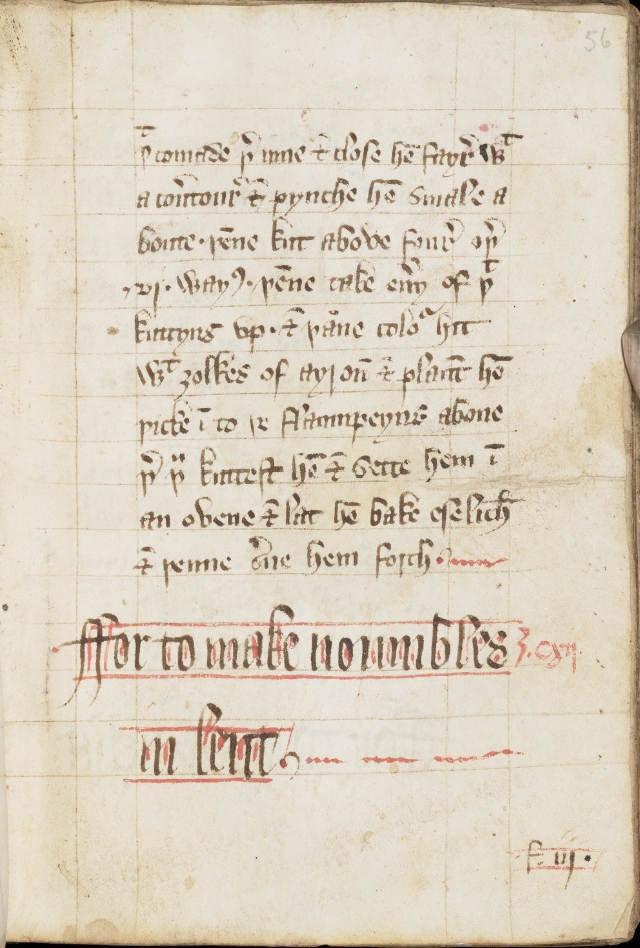

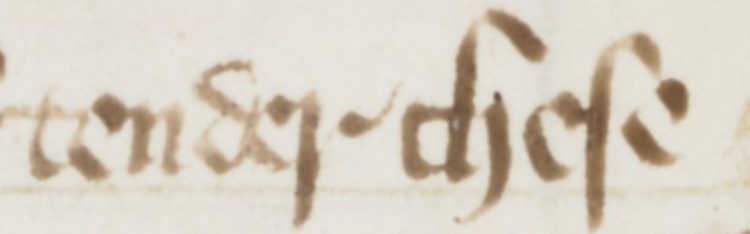

Take clene pork & boyle hit tendre & þanne hewe hit smale, & þanne bray hit smale in a morter; take fyges & boyle hem tendre in smal ale and bray hem & tender chese þerwith; þanne waysche hem in watur and þenne bray hem all togider wiþ ayroun; þenne take poudour of peper or ellis marchaunt & ayroun & a porcioun of safroun & salt; & þenne take blank suger & ayroun & flour & make a past with a rollere; þenne make þerof smale peletes & frye hem browne in clene grece & set hem asyde; þan make of þat oþer del of þat past long coffyns & do þat comade þerinne & close hem fayre with a couertoure & pynche hem smale aboute; þenne kut above foure oþer vj wayes; þenne take euery of þat kuttyng vp, & þanne colour hit with ȝolkes of ayroun & plaunt hem þicke in to þe flaumpeyns aboue þer þou kuttest hem; & sette hem in an ovene & lat hem bake eseliche & þenne serue hem forth.

How to make flame pastries (pork, fig & cheese pies)

Take fresh pork and boil it until tender and then chop it small, and then pound it smaller in a mortar; take figs and boil them in light ale until tender and pound them along with young cheese; then wash them in water and then grind them all together with eggs; then take powder of pepper, otherwise marchant, and eggs and an amount of saffron and salt [and add this]; and then take white sugar and eggs and flour and make a pastry dough with a rolling pin; then from this make small balls and fry them brown in fresh fat and set them aside; then with the rest of that make long pastry cases and put the filling into these and seal them well with a lid and pinch them finely all about; then make cuts on top, either four- or six-wise; then take all the [pastry] trimmings and then colour them with egg yolk and plant them thickly into the flame pastries, above where you have made cuts; and place them in an oven and let them bake slowly, and then serve them forth.

My edited text is from the version of the Fourme of Cury found in the John Rylands Library in Manchester (MS English 7, folio 55r-v). Translation is my own.

This is the recipe that I hope, health willing,[7] to reproduce for you soon, and will post in a follow-up. It is a recipe that needs careful interpretation – it’s certainly not the clearest method I’ve come across – and thankfully I’ve already given it considerable thought, so I will be giving you some commentary on the method along with my recipe.

I have decided that it would be good to make it as simple as possible, to encourage as many of you lovely readers to have a go at making it for yourselves. So, do expect a couple of short cuts and do expect a little modern adaptation. After all, it ain’t easy finding the likes of medieval tender chese or, for that matter, medieval ale at my local shops.

Can we find young cheese today?

I want to point out that in Britain today not only is it very difficult to buy young cheeses but they are practically unheard of in most households. Say ‘young cheese’ or ‘new cheese’ to most folk, and they won’t have a clue what you mean.

However, there is, not far from me, the famous Mrs Kirkham’s creamery and it does make a youngish Lancashire cheese. I may avail myself of some to make my flampens – or I may search for something younger still. I see a journey to a real cheese shop in my future!

In the Netherlands, young Gouda is, I understand, relatively easy to come by, so any Dutch readers might wish to use that. Let me know in the comments, below, if you can find young cheese where you live. And, of course, if you make your own, well I would really love to hear more about that.

If you would like to show your appreciation for this or any other post, you may wish to yieldeth me a cup of mead, or join the regular, monthly subscribers (you choose the amount you wish to pay).

Bibliography

Kindstedt, Paul S. Cheese and Culture: A History of Cheese and Its Place in Western Civilization (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2012), Kindle edition.

Woolgar, C. M. The Culture of Food in England 1200-1500 (Yale University Press, 2016).

[1] See tender adj. 1 and 5, Middle English Dictionary, online, tender – Middle English Compendium [accessed 13 May 2025].

[2] See grẹ̄ne adj. 3, Middle English Dictionary, online,grene – Middle English Compendium [accessed 13 May 2025].

[3] Kindstedt, pp. 143-4, explains that the thin flat wheels of the old Roman uncooked, light-pressed, surface-salted cheeses were first described in the detailed descriptions of cheese-making that appear in the early seventeenth-century, but that this shape was probably around for centuries before.

[4] Kindstedt, pp. 126-7.

[5] Citation in Woolgar, p. 52, Piers Plowman, ll. 285-6.

[6] Kindstedt, p. 99: ‘Although Varro distinguished between “soft and new cheese, and that which is old and dry,” both were made by the same rennet-coagulated cheese-making procedure, the latter being the aged version of the former

[7] I’ve not finding it easy to stand for long periods in the kitchen. I’m having physiotherapy and doing Pilates in an effort to improve things. So, hopefully, I’ll be feeling up to it soon.

What texture are we talking about, do you think? Ricotta, or fresh (grateable) provolone?

Ooh! Please, Sir, now do “chese ruayn”!

The rabbits say hello.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Texture would have varied no doubt. Things that would have affected it: skimming (less cream = firmer?); length of pressing; whether it was aged for a few days or a few weeks (still young). Ricotta is a whey cheese, no? So I don’t think we’re thinking of that. Provolone I’ve only ever eaten in slices, and it seems quite a processed ‘plastic’ cheese to me. I’m going to hopefully get to a cheese shop the other side of Manchester to see what they have that is young, and then I’ll video it.

I wrote about ruayn cheese quite a while ago. I will revisit it with a recipe at some stage.

Say hi back to the rabbits.

LikeLike

Found the ‘ruayn’ entry. Fascinating – and frustrating; I’d love some special Wensleydale…

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’d love the Courtyard Dairy. It’s such an experience. You get to sample before you buy. I have to load up on lactase enzymes 😄.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Following on from my earlier reply, this ‘fresco’ cheese might be comparable to young medieval English cheeses, or some of them, I should say: Yorkshire Pecorino (Fresco) – The Courtyard Dairy

LikeLiked by 1 person

I certainly hope you will be able to stand enough soon – it’s a great shame that someone as good in the kitchen as you, and who obviously enjoys it a lot, can’t spend their time cooking.

I’m sure if I looked hard enough I could find somewhere to get young cheese here (San Diego, California), but honestly it’s quite easy to make myself. Just get some non-fat reduced goat or cow milk (I’m not sure where I would get sheep milk, though probably could) then heat it up to 85C. Turn off the heat and add the vinegar (about one cup per liter) and BOOM the curds instantly form, quite neat to see. Let it rest about 10 minutes, then filter through a couple layers of cheesecloth to separate the curds from the whey, and your curds are young cheese. Then add whatever you want – salt, pepper, garlic, onion, herbs… I love adding caraway seeds. You can knead it with your hands, it’s almost like dough at this point.

You can eat it immediately but I find it’s better if you let it rest in the refrigerator a while. It’ll last for a while, the more water (whey) you squeeze out the longer it lasts if you don’t just homph it down.

Also, don’t throw out the whey! It’s like slightly acidic yogurt water, you can use it in a lot of things. You can just drink it (it’s a lot like Japanese pocari) or use it where a recipe calls for water, works really well for making bread and giving it that extra zing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And I just realized I have never had any of my young cheese last long enough to even attempt making ‘real’ cheese 🤣.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha ha ha! No surprise really!

LikeLike

It is fun making curds. I don’t do it regularly, though I would like to; and have a go using rennet, too. What seems to have differentiated ‘crudes’ (curds) from ‘tender chese’ in medieval England is that the latter was pressed and, as you do with yours, left to dry a little. For how long, a few days or a few weeks, I don’t know. I’m sure it varied.

I didn’t mention it in the post (I was running out of brain power!) but there’s a wonderful 13th-century record of the servants at Rochester Priory receiving a range of cheeses — young, medium, aged — as gifts at Christmastime (if I remember correctly). I’ll probably write more on cheese at some point, as it does tend to interest a lot of people.

Thanks for you kind words. I’m hoping to make my flampens in a few weeks time. We have a visit planned to the Lake District in northwest England, and on the way back we go past the best cheese shop in this part of the world.

Or there is a more local cheese shop, which has a good reputation, that I may visit sooner, if I get tempted!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Washing the ingredients in water after you’ve pounded them does sound odd, so I’ll be interested in how that goes.

I ate sheep’s cheese yesterday, possibly for the first time. It was good, but I chose the wrong things to go with it.

Visiting cheese shops is dangerous. Even visiting the cheese counter at Waitrose (which I did yesterday) is dangerous.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🤣. It would be hard to live without cheese.

On the recipe: yes, there are some perplexing instructions. A little garbled here and there. But I think things can be explained.

LikeLiked by 1 person