Re-visiting the Fourme of Cury recipe that is usually known as Tart de Brymlent

My friend Darren Turpin, professional gardener and horticulturalist at the National Trust’s Quarry Bank in Cheshire, UK, and author of the excellent website Orchard Notes, recently published on his website one of his regular posts about early English fruit cookery, A Late-C14th Recipe for ‘Tart de Brymlent’.

Note the spelling Brymlent.

This pie (it actually has a lid, so it’s not really a tart) has a filling which combines fresh fish with fruit – stored apples and pears, and various dried fruits. Interesting, was Darren’s wry assessment.

The recipe is found in Fourme of Cury, the recipe book of Richard II, first written down around 1390. The oldest and best surviving version of the text is a small book which dates to the period of Richard’s reign, and today is kept in the John Rylands Library in Manchester, known by the identifying shelfmark English MS 7, available as a digitised facsimile.

Later copies of the recipes were made, most, if not all, in the fifteenth century. Two of these are in roll-form, including the more famous British Library roll (Additional MS 5016), sadly not presently available as a digitised facsimile due to the cyber attack the library has had to deal with recently.

The other copies are part of compilations or miscellanies; in some of these the Fourme of Cury recipes are quite haphazardly mixed up with other recipes not from Fourme of Cury.1

There is some variation between individual recipes across all these manuscripts, most obviously in spelling. Sometimes the transmission process has resulted in clear mistakes; at other times it seems that small modifications have been made to a recipe. Occasionally, these more purposeful alterations help to illuminate the intent of Richard’s master cooks when the recipes were originally compiled.

I’m giving this brief overview of Fourme of Cury because it provides context to some of the information I’m going to provide, below.

Now, Darren appealed to me in his post to shed some light on Tart de Brymlent, particularly on translating and interpreting its text. No surprise to me, however, he did a very good job all by himself, so do check out his post. I will nevertheless offer a few tweaks, here and there.

Darren also wondered about the meaning of brymlent, and it is there that I wish to start, before offering my edition and translation of the recipe based upon the John Rylands Library book. I’ll also offer a few insights into the admittedly curious tart filling of fish and dried fruit.

Brymlent

I am re-reading the name of this pastry as Tart de Bry in Lent. I have two core reasons for doing so. I’m looking, first, at the manuscript context; and, second, at the recipe itself, for it yields up pertinent clues.

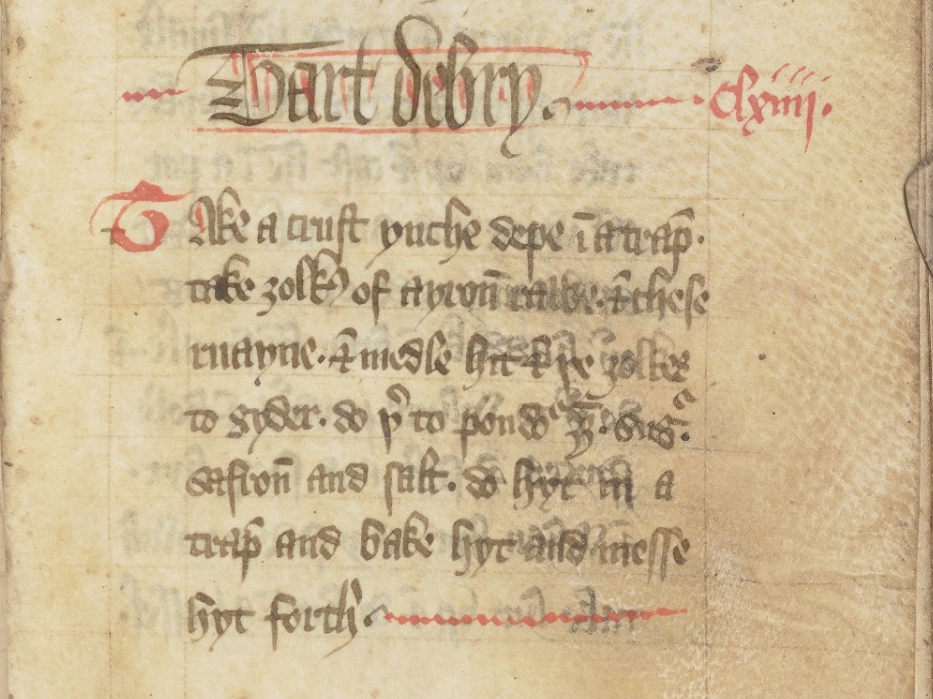

Let’s take a look at the recipe as it appears in the aforementioned, late-fourteenth-century book at the Rylands Library. It’s found on folio 77 verso.

My editorial choice to render the title as Tart de bry in lent is based on my reconstruction of the recipe name as it appears here. It is probable, though not absolutely clear, that the scribe did write Tart de brymlent. That is what it looks like, at least when one reads it initially. The word brymlent is, however, essentially meaningless.

Earlier editorial attempts to give it meaning are tentative and ultimately misplaced. In 1983, Constance Hieatt and Sharon Butler, who used the text of the British Library roll copy as the base for their edition – they didn’t know at the time about the earlier Rylands Library book – were also dealing with what looked like brymlent. The roll is textually close to the Rylands version, so this is not a total surprise.

In their glossary, they gave, ‘brymlent = brim in the sense of “full”?’, without expanding.2 Their question mark was most appropriate. I can imagine their confused faces.

The antiquarian Samuel Pegge, who created an edition in 1780 based on the same British Library roll copy – this is the edition Darren used in his post, and is the version of Fourme of Cury most readers will be familiar with, as it is online – did address more directly the –lent element of Brymlent, and suggested it perhaps meant Midlent or High Lent. He was getting there.

No one, however, questioned the possibility that scribal error was at play. I’ve concluded that it probably was, or that we are actually misreading what is there. Here’s a summary of my thesis:

In copying out the recipe title, the scribe of the Rylands Library book may have misread the minims before him, in either the exemplar he was working from or, if he was actually one of the original scribes tasked with collaborating with the master cooks in compiling the book, in his own notes.

Minims, if you’re not familiar with the term, are, in a manuscript context, those practically identical downward strokes of the quill that form the letters i, m, n, and u. Minims are notoriously difficult to distinguish when written in a group, particularly when dealing with unfamiliar words – such as the one we are focusing on here.

I propose that the scribe understood the minims for in as those for m, and then compounded the problem by compressing his bry m lent to make what appears to us to be one word, brymlent.

I think the compression is quite evident when we look at the manuscript closely, as there seems to be an attempt to squeeze in the last few letters, in order to make them fit within the ruled margin, the faint line of which you should be able to make out on the right of the page.

Thus what originally would have been the sensible bry in lent became the meaningless brymlent.

Arguably, and perhaps more simply, the scribe may not have made a mistake with his minims; after all, they are notoriously difficult for modern readers to differentiate. An originally penned i and an n written close together could easily be misread by us today as an m.

If you’re thinking that there would have been a dot above the i had the scribe been writing in, you are not entirely wrong, but there are other examples of in within recipe names where the dot is either missing or is so faint that it is barely discernible. Just look, by way of example, at Makerel in sauce on folio 52v:

Recipe context

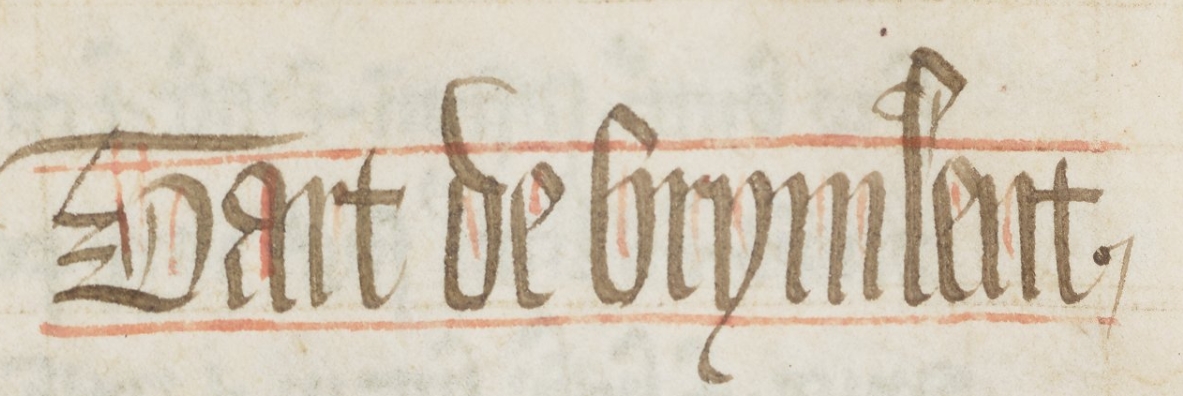

A real crux of my hypothesis is that this recipe immediately follows Tart debry, which suffers from typical medieval word-spacing and should be read as Tart de bry.

This tart’s filling was made from a beaten blend of egg yolks and full-fat cheese. Originally, if the recipe hailed from Normandy, the cheese would have been Brie, but in the recipe’s method, an English substitute, a late-season type of cheese, known as rowen, is given.

Importantly, Tart de bry would have been unacceptable for Lent, as eggs and dairy were forbidden by the Church during this most important religious festival. So, one of Richard II’s master cooks selected, or created, an alternative version of this pastry for Lent.

No dairy and no eggs. What better title, then, than Tart de bry in lent?

Most importantly, the slightly later version of Fourme of Cury found in the fragmentary British Library, Harley 1605 manuscript has the recipe title Tartes of lenton (Tarts of/for Lent) as the name of the dish.3 At least one scribe understood what was meant!

Let’s now take a look at the text for the two recipes together, and do a bit more theorising about them, the latter in particular.

My edition and translation

Tart de Bry (164)

Take a crust ynche depe in a trape; take ȝolkes of ayroun rawe & chese ruayne, & medle hit & þe ȝolkes togyder; do þerto poudour gynger, sugur, safroun and salt; do hyt in a trape and bake hyt; and messe hyt forth.

Tart of Brie

Take a one-inch-deep crust in a flan-dish; take raw egg yolks and rowen cheese, and mix it and the yolks together; add to this ginger powder, sugar, saffron and salt; do it in a flan-dish and bake it; and serve it forth.

Tart de bry in lent (165)

Take fygus, raysouns, & waysche hem in wyne & grynde hem smale wiþ apples & perus clene pyked; take hem vp & cast hem in a pot with wyne and sugur; take calwar sawmoun ysode, oþer codlyng, oþer haddok, & bray hem smale; & do þerto whyte* poudours & hole spyces & salt and seeþ hyt; & whan hyt is ysode ynowh take hit vp & do hit in a vessel, and let hyt kele; make a coffyn an ynche depe & do þe fars þerinne, and plaunt hit aboue with prunes and damysyns, take þe stones out, & with dates quarterd & pyked clene; and couer þe coffyn and bake hyt wel; and serue hyt forth.

Tart of Brie in Lent

Take figs, raisins, and wash them in wine and grind them small with apples and pears, picked clean; remove them and cast them into a pot with wine and sugar; take cooked calver salmon, or codling, or haddock, and pound them small, and add thereto [with] powders and whole spices and salt and simmer it; and when it is cooked enough, remove it and put it into a vessel and allow it to cool; make a pastry case an inch deep and put the forcemeat into it, and arrange on top prunes and damson plums – take the stones out – along with dates, quartered and picked clean; and cover the pastry case and bake it well; and serve it forth.

* whyte is probably an error for wyth (of which there are many variant spellings). Correcting this allows the method to make better sense, as it explains that the fish with spices are added to the preceding pot. Otherwise, we are not told how and when the fruit and fish are combined. Moreover, whyte poudours, is not used elsewhere in Fourme of Cury, though poudours by itself is used several times.

Fish and fruit?

As it so happens, I recently revisited the Tart de bry in lent recipe whilst editing my work for an initial draft of my book. I had always felt that the fish there was almost treated with disrespect. It being cooked three times and it being pounded finely seemed at first to me to be culinary overkill.

But then I thought more about what a medieval cook was trying to do in providing an alternative pastry for Lent. Medieval cooks were skilful, and they were particular experts in making Lenton fare not seem like a total drag. Fish upon fish upon fish is a total drag, I’d say.

I think what we are witnessing here is a medieval cook, if not imitating, then approximating the texture of the filling of the preceding Tart de bry.

That pastry had as its filling what was essentially a very rich custard of egg yolks and full-fat cheese, sweetened to some extent with sugar and spiced with ginger. It would have set quite firmly.

Which reminds me: in my first experiment with Tart de bry, I chose to make small individual tarts, and let’s just say my ratios were awry, and I ended up with what might best be described as substitutes for ice hockey pucks.

Before continuing, I should state at this point that I have yet to carry out an experiment to substantiate my claim, here, but please bear with me. You can tell me what you think in the comments section at the end of the post.

We should note that the fish, including calver salmon, which means the very freshest salmon, is first described as ysode. I’ve translated this as ‘cooked’ but more precisely it means cooked in a liquid, such as a broth, as ysode is the past participle of the verb sethen, which in a culinary context means ‘simmer’ rather than ‘boil’.

This likely meant that the fish was cooked in a fish broth – fish heads, tails, etc, in water – meaning the cooked fish had the potential to take on some of the gelatinous property of the stock, especially if it were allowed to cool in the broth after cooking, before then being pulverised.

The fish was then further simmered along with spices – these were obtained from both spice powders, i.e. spices already ground and mixed, probably at a spicier’s shop, and from whole spices freshly ground in the kitchen quarters.

This simmering was done inside the pot already containing the ground-up fruits, wine and sugar – perhaps just a little wine was needed.

The initial washing in wine of the figs and raisins, by the way, may refer to them being soaked to plump them up; and the apples and pears would have been fruits stored after the previous harvest, in view of the time period of Lent.

Then the whole mix was allowed to cool in a vessel. Once cooled, it is referred to as a fars, a stuffing or forcemeat – some folk, like me, still like to use the archaic farce. A farce is thick, thick enough in this case to be planted with dried fruits – prunes, damson plums, and dates.

Once this was all baked in the pastry case, covered with a pastry lid, and allowed to further cool, the filling of the pie must have resembled that of the Tart de bry – not in its flavour profile but in its texture. If ginger was one of the spices chosen, then there would have been a flavour cross-over, too.

On reflection, I don’t think the flavour of the fish was the key consideration in this dish. I think its, shall we say, rather brusque treatment would have lessened its flavour. If fish flavour had been truly important, then the cook would have started out with raw fish, I believe.

It was the sweetness and flavours of the fruits and spices that were meant to be noticed, but the texture did matter. Rather than serving up a sloppy gloop of puréed fruits, the processing of the fish would have created a somewhat gelatinous medium for the fruit, ultimately giving a texture for the pie’s filling that mimicked the firm custard of the set egg yolks and cheese of Tart de bry. A perfect Lenton alternative, we might say.

Indeed, a Tart de bry to be eaten in Lent.

If you would like to support my independent research, please consider a small donation or joining the list of monthly subscribers. Thank you.

Notes

- See Constance B. Hieatt & Sharon Butler (ed.), Curye on Inglysch: English Culinary Manuscripts of the Fourteenth Century (Including the Forme of Cury), Early English Text Society Supplementary Series 8 (London, New York, Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1983), pp. 158-65, for a list of most of the manuscripts and the sequence of recipes in each of them. The editors were unaware of the John Rylands Library manuscript at the time their book was written and published. ↩︎

- Hieatt & Butler, p. 218. ↩︎

- Sadly, this is currently no longer available as a digitised facsimile, but I was able to check this a while back, before the library’s cyber attack. ↩︎

This was fun! Particularly the section on minims. (I remember my triumph when I figured out that IIIIIIIIIIIIIII meant ‘minimum’)And fish with fruit isn’t all that weird. Pesce in saor? Some recipes for escabeche? There’s even a Moroccan recipe for shad stuffed with dates…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad it was fun. I do like the minimum joke. I do think the pie’s filling sounds a bit weird on first reading, notwithstanding the modern day fish n fruit delicacies. But we have to get into the medieval mindset, I guess. Besides, I do quite fancy trying the recipe for fish in Egredouce, i.e. sweet and sour sauce, which uses great raisins. Could be a winner, winner, fish dinner! 🤣

LikeLiked by 1 person

I also like the idea of using the fish’s own gelatin as a setting agent. And I agree with you about Egredouce!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I should have phrased it that way, just to make it clearer.

Fish Egredouce on your menu, then? I’ll have to experiment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I can totally see that mis-scribing happening, since I honestly find these manuscripts very hard to read, very much form over function. Not entirely since I do admire the precision in their hand (certainly more than I could muster!) and it would be very easy to imagine worse (clumsy cursive), but this was obviously not designed as well as Orgham. I’ve gotten a lot better since starting with your videos, but still will mostly leave it up to you! Bad ligatures and bad kerning are the bane of a lot of documents in a lot of languages.

And as a fisherman who eats a lot of fish I can definitely see how this could work. Obviously you would not add the fish to make the fruit taste better, but as you say, fish could make a pretty decent base filler for the fruit and spices as long as you knock down the fishiness – and most river fish are not that fishy unless you let them sit for far too long. I think this could work great with a fresh rainbow trout.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your fish thoughts are very helpful. Thank you. I was actually thinking I should try it with trout.

On scripts, there are some that defy my brain. They’re just so hard work. 🤣 I do by now feel quite cosy with the Rylands Fourme of Cury, but it’s to be expected after staring at it for so long.

LikeLiked by 1 person

WP is NOT letting me like your comments, and has not been for a while because of whatever Javascript mis-scribing they have going on with Firefox and Vivaldi, please just figure any time I am responding I am liking, because I am. Apologies if you are getting multiple notifications because I am seeing nothing.

And yes, I think you have to be the #1 Fourme of Cury expert at this point, or way up there! All your posts about it are genuinely interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No worries.

LikeLike

And thanks for the compliment .

LikeLike

Ah, now after logging out and back in I see a like from me which it pretended did not exist… I’ll keep trying to make that happen just for metrics.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not one that I’ll be trying, although the cheesecake that precedes it looks like fun. You have to admire the person who looked at a cheesecake and thought “I want to make a cheesecake without cheese or eggs. I know, I’ll use a fish. It’s for Lent after all”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed! Needs must.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brilliant stuff, Dr. Monk! “Brymlent” = “Bry in Lent” has to be correct, surely. Now you’ve pointed it out, you really can see that the spacing of those minims is intended to represent characters, rather than a single ‘m’. And the insight on the texture of the filling – that it was intended to replicate the presumably allowed-year-round ‘Bry’ version of the tart – makes a lot more sense than it being a simple haddock-and-apple pie. Thank you very much indeed for taking the time to unpack everything so comprehensively. I’ve updated my original post to point folks in this direction as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was great fun looking into it. The ‘bry in lent’ part came to me a couple of years ago, but the realisation of what was going on with the filling was very recent.

Others have also pointed me to French recipes of the period that are more explicit about using fishy things as an alternative to cheese, so I will be checking those out, too.

It was really great to be able to respond to your own post. No doubt I will be picking your brain more on fruit related matters, particularly on apples and pears.

LikeLike