- Turnips & penance

- Turnips in medieval England

- Would Richard II really have eaten turnips?

- Recipe: Turnip pottage for a king (serves 3-4)

- Notes

- Selected bibliography

I have to confess, turnips have never inspired me in the kitchen. Not until now. Or, more precisely, not until about a week after all the feasting of Christmas had finished.

It was then I started thinking about cooking lighter dishes. Food that was a nod to penance for all the indulgence, but, critically, food that was still tasty.

So I browsed the draft material for the book I’m writing about Richard II’s cookery book Fourme of Cury, specifically to the chapter on nuts and vegetable dishes. It would surely have something appropriate. And there it was, Rapes in potage, that is, a pottage, or stew, of turnips.

Rapes in potage

Take rapes & make hem clene & waische hem clene; quare hem, perboile hem, take hem vp, cast hem in a gode broth & seeþ hem; mynce oynouns & cast þerto safroun & salt and messe hit forth with poudor douce. In the same wyse pastronakes & skyrwittes.

Turnip pottage

Take turnips and clean them off and wash them; dice them; parboil them; take them and put them in a good broth and simmer them; mince onions and throw these in; add saffron and salt; and serve it forth with powder douce. In the same way one can make it with parsnips and skirrets.1

Turnips & penance

I’d noted, there, that in the century after King Richard, turnips had an association with penance. In a mid-fifteenth-century English retelling of the life of the monk and mystic St Hilarion (c. 291-371), we are told that this desert anchorite had dedicated his whole life to penance, and to prove it he ate fifteen turnips both day and night.2 He probably deserved his sainthood for that alone, don’t you think?

Hilarion’s excessive turnip consumption was most probably narrative embellishment, and, moreover, he never lived anywhere close to England, being born in Palestine, near modern-day Gaza, and living around there for decades before ending up in Cyprus, via Egypt, North Africa and Sicily.3 Hilarion’s turnips were local to wherever he lived, so not directly helpful as I wanted to know about turnips in medieval England.

Turnips in medieval England

Words used for ‘turnip’ in medieval England:

Old English: næp, tun-næp; Anglo-Norman: navet; Middle English: nep, rape: Latin: rapa/rapum

The use of turnips in medieval England may have been largely confined to the realm of medicine until the late-fourteenth century. Though by no means appearing extensively in medical recipes, the turnip does show up both in the early and late medieval periods. Here are two examples:

A treatment against wens, or tumours, of the heart is found in an Anglo-Saxon medical text, preserved in a manuscript dating to around 1000. The recipe includes the instruction to ‘take a small turnip’, nim […] smælne tunnæp, as one of the ingredients for a boiled concoction.4

In an Anglo-Norman text, the healer is directed to take the leaf of a turnip, La foile pernés del navet, and to mix it with the white of a fresh egg to form a poultice for a canker (an abscess or ulcer).5

Hard evidence of the use of turnips in a food or culinary context before Richard’s recipe in Fourme of Cury, written around 1390, is however lacking.

Turnips do not appear in any of the prior English cookery works that date from the end of the thirteenth-century. Of course, these works are aristocratic, so the absence of turnip recipes does not speak to the diet of the likes of farmers or labourers. Perhaps some of them grew turnips in their gardens, but evidence is wanting.6

It has been implied by one historian that turnips were widely available in London as a staple food as early as 1300, but I haven’t seen any direct evidence as proof of this.7 On the contrary, the evidence for the cultivation of turnips as garden produce this early is absent, as we shall see. And the growing of turnips as a field crop in England did not take place until the seventeenth century, and, even then, they were grown for animal fodder.8

Turnips may have been eaten commonly in parts of mainland Europe at this time,9 but the fashion for turnips had not travelled across the English Channel, it would seem. I have not been able to find any evidence for imports to England of the turnip in the decades around 1300, though there are multiple records for other vegetables, such as onions and garlic, being imported at this time.10

Turnips in gardens

The widespread growing of turnips in English gardens in the early and mid-fourteenth century is not apparent. Master John Gardener, who may have been a chief gardener for Edward III (1327-77), did not include them (nor carrots, parsnips, and skirrets) in his poetic treatise, The Feat of Gardening.11

The absence of root-crops in John Gardener’s work led the late John Harvey, garden historian extraordinaire, to observe that ‘the general introduction of roots such as skirret (Sium sisarum), carrot, parsnip and turnip, seems to belong to the fifteenth century.’12

The turnip is mentioned in a herbal written by the friar, botanist, and healer Henry Daniel, who flourished towards the end of the fourteenth century, and had his own specimen garden near London.13 His observation that the root of the turnip was good for pottage suggests he, at least, had tried turnip this way, but it may perhaps also suggest that this was not well-known at the time in England.14

We should note that Daniel was an experimental botanist with a particular interest in the healing properties of plants. His observations on plants in his herbal are frequently personal, based on his own experiences as a keen gardener. His supplementary comments about the food value of certain plants, including the turnip, may also be understood as part of his aquired, practical wisdom. He evidently wished to pass on his knowledge to the widest possible audience, his herbal being written in the vernacular, not Latin.15

Indeed, it is likely Daniel’s information fed into the theory of diets, Dietarium, written in 1424 by Master Gilbert Kymer for Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, Richard II’s second cousin. Kymer, who was Humphrey’s physician, lists numerous plants suitable for pottage, including turnip.16

Would Richard II really have eaten turnips?

So what about Richard II’s recipe? Would he, the king, have actually eaten this pottage of turnips? We cannot say categorically that Richard ate every single dish that appears in his Fourme of Cury. However, there are a few things to consider that may lead us to think he would have.

Other vegetable pottages

We know that Richard, and other medieval monarchs, didn’t just relentlessly chow down on boar’s head, roasted peacock, venison, and the like. Though elite meat dishes appear abundantly in both his cookery book and on menus for feasts that we know he attended, vegetable-based pottages were also served alongside them. Outnumbered they were, but they were still there!

Let’s take the two dinner menus of Baron Thomas de Spencer by way of example. Created for the visit of the king around 1397, we find a dish called vyolette, likely a pottage containing violets,17 and two pottages made from dried peas, recipes for which actually survive in Fourme of Cury – and which I promise I will make for you at some point. These were pesson, a pea purée, and bruet of almayne (German broth), which in Fourme of Cury, reads somewhat like a posh version of mushy peas!18

We can see from the two pea recipes in Fourme of Cury that something as basic as dried peas were elevated. Yes, dried peas were a key ingredient in many a peasant woman’s cooking pot, but in the king’s kitchens, peas were strained through a cloth and seasoned with sugar and saffron, in the case of the pea purée; or removed laboriously from their skins and spiced with ginger and saffron, in the case of the German broth.

What we see with our turnip pottage is the same fancifying of rather plain food, food that would typically be associated with lower classes. In other words, turnips fit for a king.

We should also consider that a pottage of turnips was likely viewed as healthful. If Richard II were served it, it would have been carefully prepared by one of his master cooks, and with the nod of approval of his physicians who, we are told in the introduction to Fourme of Cury, gave their assent to the recipes.

Salvation of the soul and penance

I can’t help thinking that there was something of the act of atonement in eating a root vegetable, along with humble onions, in what was essentially a simple pottage, spices notwithstanding. St Hilarion’s story of munching on turnips every day and night, though penned decades after Richard II’s reign, nevertheless casts a certain penitential perspective on earlier turnip consumption.

Moreover, all medieval monarchs, at least in principle, would have had the salvation of their soul uppermost in their mind at certain religious festivals, such as during the Lenten period leading up to Easter, or if they wished to atone for something they regretted doing.

Richard II was deeply and openly pious. We only need to look at the Wilton Diptych, commissioned for him, to see that his Christianity was overt. And yet he was a complex, even volatile ruler, prone to resentment and vengeance, writing perceived wrongs through violence if necessary.

The Wilton Diptych.

According to the National Gallery, it was made for Richard II (r. 1377-99) during the last five years of his reign.

Richard is depicted in the left panel, kneeling. He is being presented to the Christ child and the Virgin Mary, in the right panel, by Edmund and Edward the Confessor, England’s patron saints, and his personal patron, John the Baptist.

For an excellent overview of his reign, including his acts of vengeance against the Lords Appellant, the new entry in the online Britannica by Nigel Saul is well worth a read.

It is possible turnip pottage may have been prepared by one of Richard’s master cooks for Lenten fasting, in which case he would have used a vegetable broth to comply with religious law.

And, who knows? The king may have requested turnip pottage whenever he feared he had wavered in his commitment to his belief that it was ‘his duty to ensure the acceptability of his government to God’, as Saul expresses it.

That said, raising the turnip sufficiently for it to become royal penitential fare was perhaps something that crossed the mind of the cook. So expensive saffron was added to the recipe to imbue the broth with a golden hue.

The final instruction to messe hit forth with poudor douce may suggest that as the pottage of diced turnips was brought to table, a sprinkling atop of expensive spice powder was part of the performance of serving it up for the king.

Indeed, it is easy to imagine one of Richard’s documented silver spice-plates serving as the vehicle for the powder douce.19 Perhaps the one enamelled on the foot with an image of Jesus, spiceplate… enaymellez sur la pee de Jhesu’,20 would have been most appropriate.

Even in a time of excoriating the soul, a dash of elegance would not have gone amiss.

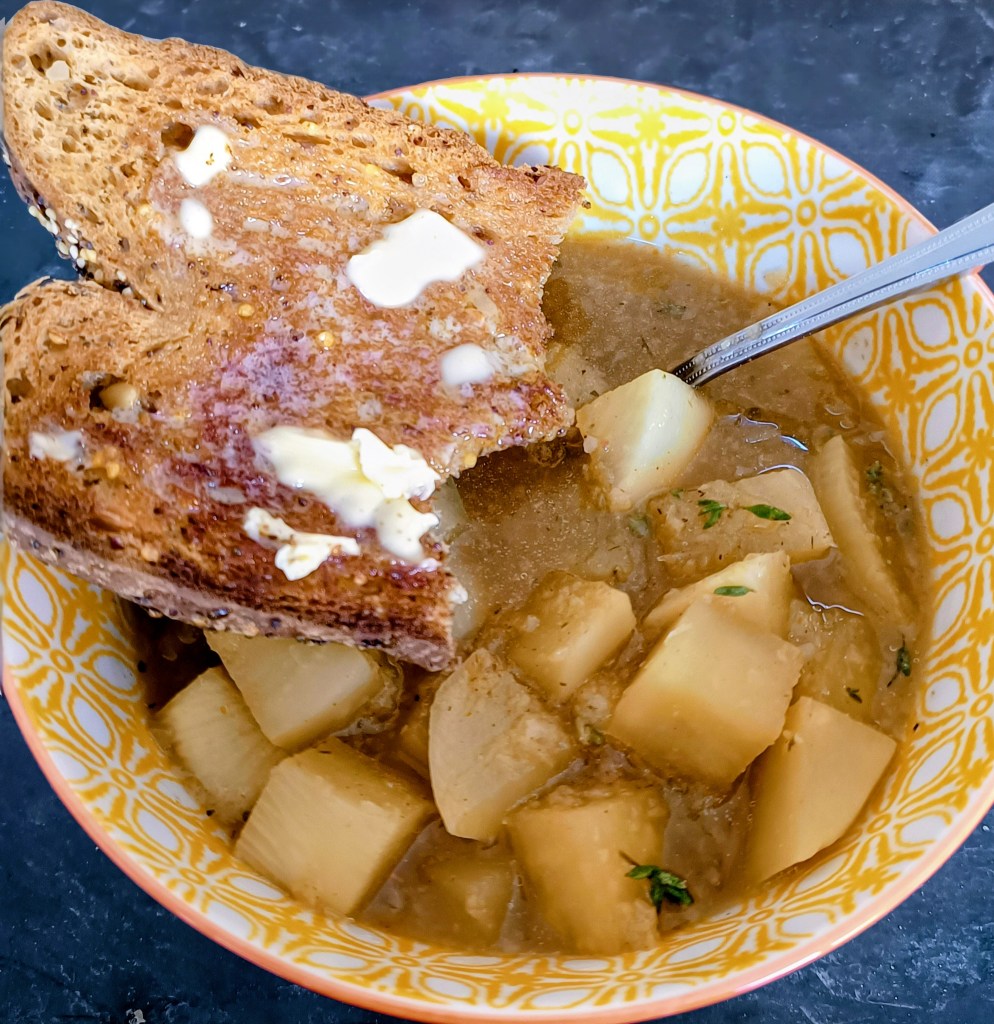

Recipe: Turnip pottage for a king (serves 3-4)

I have adapted the original recipe:

The frying of the minced onions is not specified in the original, but the browning of onions does appear elsewhere in Fourme of Cury, and adds a layer of flavour that elevates this dish even further.

I chose spices that may have been in a powder douce mix, though I did not grind the Indian bay leaves, but left them whole in the broth. I also added the spices near the beginning of the cooking, quite simply because it is a better culinary technique than sprinkling them on at the end.

Thyme leaves as a garnish is my own innovation.

Ingredients

1 large onion, about 200g (7 oz)

glug olive oil, about 2 tablespoons

2 large turnips, about 675g (24 oz) when peeled

850 ml (29 fl oz) chicken stock or broth, preferably homemade

1 level teaspoon ground ginger, preferably freshly ground

1 level teaspoon ground cinnamon (Ceylon, not cassia), preferably freshly ground

2 cloves, ground

pinch saffron strands, about 10-12

2 or 3 Indian bay leaves, i.e. cinnamon leaves (or substitute ordinary bay leaves)

sea salt, to taste

fresh thyme leaves to garnish

Method

First, peel and mince your onion. If you don’t have a food processor, finely chop the onion.

Heat the olive oil in a frying pan, add the onion, stir thoroughly.

Fry slowly on a medium-low temperature, ocassionally stirring. It will take about one hour, or more, to turn the onions to a caramelised brown state.

In the meantime, peel and chop the turnips into 2 cm (¾ inch) cubes.

Place into a large pan along with the stock/broth and Indian bay leaves. Bring to a simmer.

Mix the ground spices (ginger, cinnamon, cloves) together, and crumble in the saffron. Add this mix to the pan.

Cook the turnips for about 12 minutes, or until they are tender but with a little bite remaining.

Add the browned onions to the pan, and stir thoroughly.

Ladle your turnip pottage into bowls and sprinkle a few thyme leaves on top. Serve with buttered toast.

If you would like to support my work as an independent scholar, you can make a one-off donation by going to Yieldeth me a cup of mead.

Or you may wish to become a monthly subscriber.

Thank you!

Notes

- Text edited directly from the John Rylands Library version of Fourme of Cury, c. 1390: Manchester, John Rylands Library, English MS 7, folio 13r-v. The translation is my own. ↩︎

- Cited in Woolgar, p. 110, and n. 89. ↩︎

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Hilarion ↩︎

- Pollington, pp. 216-17, no. 89. Pollington translates it as ‘slender garden rape’. ↩︎

- See, by way of example, the so-called ‘Physique rimee’, in Hunt, p. 182, ll. 1073-76. ↩︎

- See Dyer (2006) and (1994), esp. chs. 5 and 7; but he is silent on turnips. ↩︎

- Adamson (2004, Kindle ed.), ch. 3 ↩︎

- See the entry ‘Norfolk four-course system’ in the online Britannica. ↩︎

- Adamson (2023, Kindle), section on ‘Agricultural trends’. ↩︎

- I consulted Gras, particularly ch. 9. ↩︎

- Harvey (1985). ↩︎

- Harvey (1984), p. 92. ↩︎

- Harvey (1981), p. 179. For more detail on Daniel, see pp. 159-62; also Harvey (1987), and Keiser. The latter two are available via Jstor. ↩︎

- Harvey (1987), p. 89. ↩︎

- For an overview of Daniel, see the Henry Daniel Project. ↩︎

- Harvey (1987), p. 89, and p. 93, n. 77. ↩︎

- Hieatt & Butler, p. 39, no. 1, and p. 222, violet. ↩︎

- Hieatt & Butler, p. 39, no. 2. ↩︎

- There are numerous entries for spice plates in Richard II’s inventory of treasures. For the spicery department, where the more ‘day-to-day’ items are listed, twelve silver gilt and nine white silver spice plates are listed; see Stratford, p. 218, nos. R796 and R797. For the more elaborately decorated spice plates, see the index in Stratford, p. 464. ↩︎

- Stratford, p. 222, no. R845. ↩︎

Selected bibliography

Adamson, Melitta Weiss. Food in Medieval Times, Greenwood Press, 2004, Kindle Edition).

Adamson. Melitta Weiss. ‘Plants as Staple Foods’, in Alain Touwaide (ed.), A Cultural History of Plants in the Post-Classical Era, vol. 2 of A Cultural History of Plants, ed. Annetter Giesecke and David J. Mabberley (Bloomsbury, 2023, Kindle Edition).

Dyer, Christopher. Everyday Life in Medieval England (The Hambledon Press, 1994).

Dyer, Christopher. ‘Gardens and Garden Produce in the Later Middle Ages’, in Food in Medieval England: Diet and Nutrition, ed. C. M. Woolgar, D. Serjeantson, and T. Waldron (Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 201-214.

Gras, Norman Scott Brien. The Early English Customs System: A Documentary Study of the Institutional and Economical History of the Customs from the Thirteenth to the Sixteenth Century (Harvard University Press, 1918).

Harvey, John. Medieval Gardens (B. T. Batsford Ltd., 1981)

Harvey, John H. ‘Henry Daniel: A Scientific Gardener of the Fourteenth Century’, Garden History 15.2 (1987), pp. 81-93.

Harvey, John H. ‘The First English Garden Book: Mayster Jon Gardener’s Treatise and Its Background’, Garden History 13.2 (1985), pp. 83-101.

Harvey, John H. ‘Vegetables in the Middle Ages’, Garden History 12.2 (1984), pp. 89-99.

Hieatt, Constance B., & Sharon Butler (eds.). Curye on Inglysch: Culinary Manuscripts of the Fourteenth Century (Including the Forme of Cury), Early English Text Society, S. S. 8 (Oxford University Press, 1985).

Hunt, Tony. Popular Medicine in Thirteenth-Century England (D. S. Brewer, 1990).

Keiser, George R. ‘Through a Fourteenth-Century Gardener’s Eyes: Henry Daniel’s Herbal’, The Chaucer Review 31.1 (1996), pp. 58-75.

Pollington, Stephen. Leechcraft: Early English Charms, Plant Lore, and Healing (Anglo-Saxon Books, 2000).

Stratford, Jenny. Richard II and the English Royal Treasure (Boydell Press, 2012).

Woolgar, C. M. The Culture of Food in England 1200-1500 (Yale University Press, 2016).

This sounds delicious – and timely, since I’ve been looking for some new winter veg.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It surprised me how good turnips can taste!

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s an old Madhur Jaffrey recipe for turnips that I have made and liked. But I sold almost all my cookbooks (well, book-books, too) when I moved.

Speaking of which, how’s the new house treating you?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ooh! I’ll check my old Madhur Jaffrey book.

It’s going well. Things to do, but we’re getting them done gradually. I really love it here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Splendid news!

Madhur Jaffrey Quick and Easy, if I remember rightly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Och! Neeps ‘n’ Tatties Laddie!so glad you’ve done the humb

LikeLiked by 1 person