A corner of the kitchen in the palace lodgings of Portchester Castle. Photo by Ray Gairns

I recently had the great pleasure of visiting Portchester Castle, a medieval coastal stronghold standing within the magnificently preserved walls of a Roman fort, commanding the north end of the huge natural harbour of Portsmouth, in Hampshire, England.

(For a beautifully illustrated overview of the history of Portchester Castle, head over to English Heritage.)

Though I knew – somewhat vaguely, I have to admit – of the Roman fort being one of the so-called ‘forts of the Saxon Shore’, built over the course of the third century to counter the threat of Saxon pirates, I had not appreciated the connection between its subsequent medieval castle and King Richard II (r. 1377-99). And, as regular readers of this blog know well, Richard II matters to me, since it was he who commissioned the cookery book Fourme of Cury – the principal subject of my current food history project.

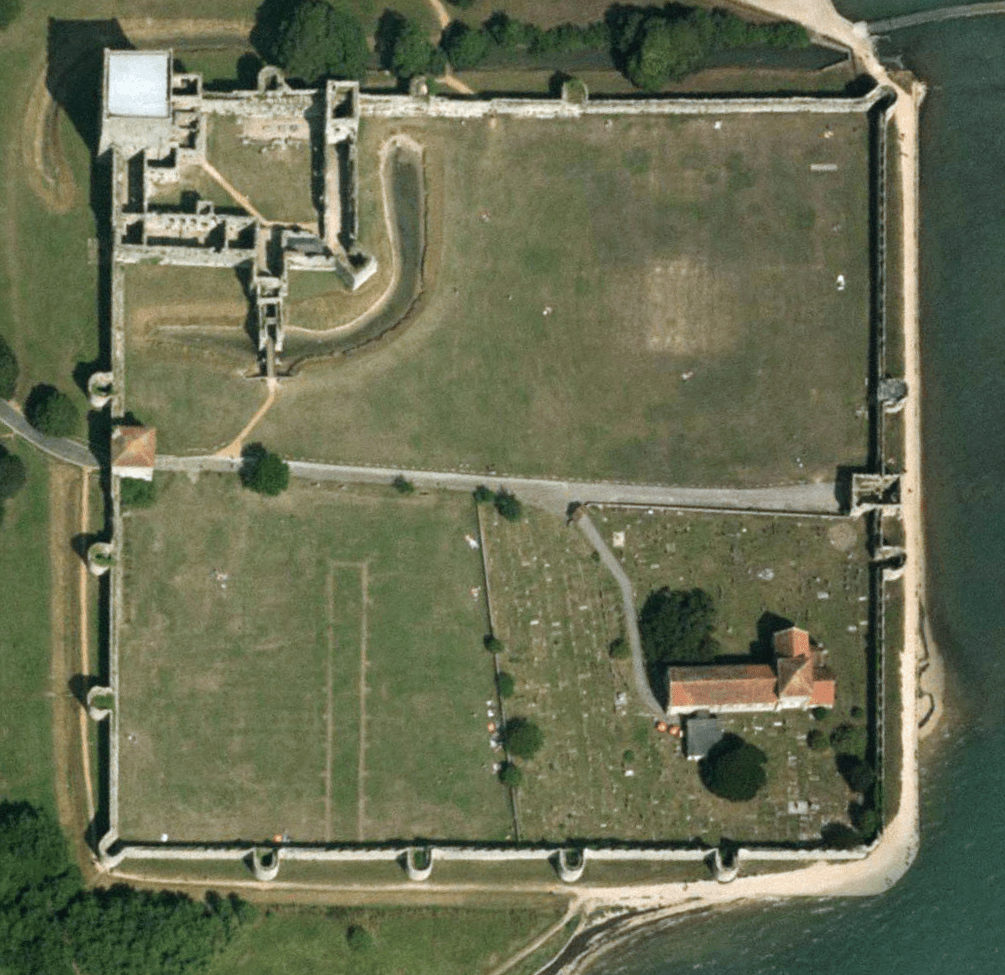

Potchester Castle, aerial shot. The inner bailey, in which Richard II’s palace lodgings are situated, is the small walled rectangle in the top left corner. (Hampshire Hub and University of Southampton via Wikimedia)

The residential apartments within the inner bailey of Portchester Castle were built by Richard ‘as part of his reorganization of the castle between 1396 to 1399’,[1] that is, during the last three years of his reign.[2] Wonderfully, a complete set of accounts for the construction work of this ‘miniature palace’ survives,[3] and we know that the master mason Walter Walton was the supervisor.[4]

(You can see a digitised copy of one of the related documents here at the National Archives website.)

The palace, alas, is now a ruin, though English Heritage describes it as ‘the most complete series of royal apartments to survive from the late 14th century’.[5] Indeed, with my friend Mary reading out from the English Heritage guidebook, I was able to walk around the palace with a decent grasp of the layout and purpose of each of its rooms.

And – as I get excited (some might say giddy) about this type of thing – I started imagining myself dining with Richard II in the great hall, or even hobnobbing with him in his private chambers, and – most exciting of all – chopping up capons and mincing onions in the kitchen!

To my chagrin, it turns out that there is no record of Richard ever visiting Portchester. It’s possible the domestic improvements at the castle were for the benefit of Roger Walden, the king’s treasurer and future archbishop of Canterbury, who, along with his brother, was keeper of the castle from 1395. Indeed, a grant of lands from Richard to the Walden brothers refers to ‘their purpose to urge the king to repair the castle’, which, as Nigel Saul intimates, supports this hypothesis.[6]

So, in a nutshell, the ‘palace of Richard II’ at Portchester Castle is of Richard’s doing but it probably wasn’t for his own comfort. Still, I can’t get over the distinct possibility that this amazing place, with its kitchen and great hall, would have had folk from Richard II’s circle being fed and watered, so to speak.

Now, I could go on and ply you with bushels of regurgitated facts about Portchester Castle and Richard’s palace, but I want to instead focus on the rather poky kitchen in the palace – and divert you, hopefully, with a few culinary musings.

Cooking in the palace kitchen

Here’s the stairway in the corner of the kitchen that led to the first floor. The stairs were used to carry up the finished dishes to the great hall.

Photo by Ray Gairns

The kitchen of Portchester Castle’s palace is surprisingly small, measuring (according to the scaled drawings at the back of the English Heritage guidebook) a mere 22 feet by 22 feet (6.7 metres by 6.7 metres), a neat square that I certainly wouldn’t mind for my own culinary exploits, but one that I imagine would have been quite constraining whenever the cooks had to produce a substantial spread of dishes for their lord and his entourage. Let’s say that the kitchen’s size would have demanded careful choreography in order to get everything cooked in an orderly manner.

This got me thinking about possible dishes the cook and his team might have found easiest to prepare. Moreover, John Goodhall, architectural historian and author of the castle guidebook, suggests the kitchen had a central fire place[7] – terribly old fashioned, Richard – so I think this may have limited, though not eliminated, the capacity for spit-roasting, which by the fourteenth century was, in elite households, being done in large chimneyed hearths set within an outer wall.[8] One example of a particularly enormous hearth survives in Kenilworth Castle, owned by John of Gaunt, Richard’s uncle, measuring 78 feet (23.8m), no less![9]

Perhaps, then, the most practicable method of cooking in this relatively small kitchen was pot cooking, that is, the making of potages, as the medievals would have put it. We shouldn’t just be thinking here of simple broths of grains and legumes, and certainly not, as Peter Brears handsomely describes, the ‘grim and gritty gruel, unskimmed, smoke-flavoured and foul’ that perhaps comes to mind whenever ‘pottage’ is mentioned in the world of reenactment.[10] We should remember that potage at its most basic level meant a dish cooked in a pot.

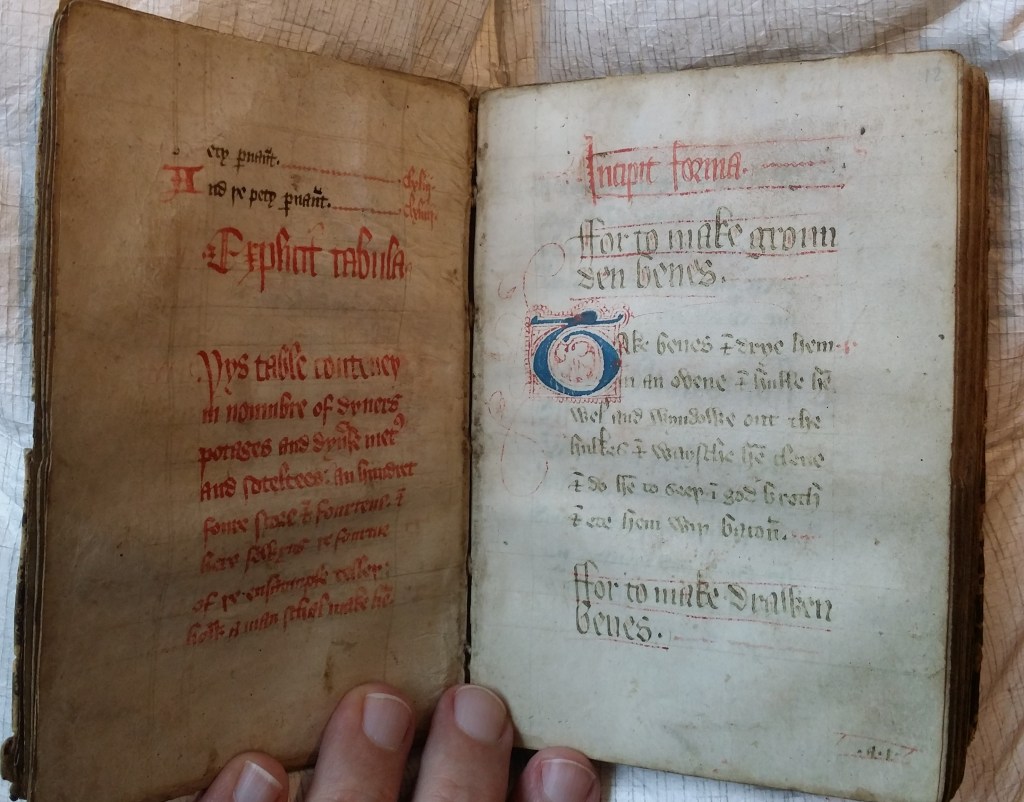

To give us some idea of what pottages may have been cooked for those dining in Portchester Castle’s palace lodgings, I have chosen three dishes from the master cooks of Richard II, specifically from their compilation of recipes in Fourme of Cury, Richard’s authorised treatise on cookery, produced, it is thought, around 1390. Of course, many more than three dishes may have been regularly served at a medieval lord’s table, but I thought it might be helpful to present to my non-medieval readers what in modern parlance we might call a main, a side and a dessert.

If, by the way, you’re thinking that a king’s cookery book would have been too high and mighty for the brothers Walden, then we should remind ourselves that, despite his purportedly humble origins (the son of a butcher, allegedly), Roger Walden had been advanced to the position of Treasurer and elevated to the See of Canterbury during the last few years of Richard’s reign.[11] He was an elite.

Indeed, though we might kindly describe the kitchen as bijou, this was still a palace with a great hall and private chambers. We know that in later years, royals visited Portchester Castle, presumably staying in the palace lodgings. Anne Boleyn and Henry VIII were there in October of 1535, and Elizabeth I held court at the castle in 1603.[12]

Regarding the great hall, where the lord and his guests would dine,[13] this was a splendid and airy affair, open to the roof and lit down one side by high windows, the glass of which was decorated with coats-of-arms and heraldic borders. A carved stone frieze depicting heraldic beasts ran around the top of the interior. Tapestries may have hung from its walls and no doubt the central square hearth provided a prodigious fire to warm and welcome its guests.[14]

In short, then, this palace was worthy of royal potages.

That’s me, folks! I’m standing in a storeroom on the ground floor of the south range of Richard II’s palace lodgings. The doorway behind me led to what was the courtyard. Above, you can see the windows of the first floor great hall.

Photo by Ray Gairns

Three pottages for Portchester

The following three dishes from Fourme of Cury were all cooked in a pot. I’ve made all three myself and have found each one delicious; and moreover, they would not disgrace a medieval lord’s, or even king’s, table.

First is Chykens in hocche:

Take chickens and scald them; take parsley and sage but no other herbs, garlic and grapes, and stuff the chickens full and simmer them in good broth so that they may be gently boiled in it; dish them up and cast on powder douce. (My own translation.)

This dish of poached chicken in parsley broth would have been ideal for cooking in a large pot or cauldron. The meaning of hocche likely derives from Old French houssié, cook’s jargon for a parsley broth.[15]

As stated, the chickens would have been prepped first by scalding them in boiling water in order to remove the feathers more easily. As Brears observes, whole chickens would also have been drawn at this stage (meaning they had their innards, or giblets, extracted), and had their heads and feet removed.[16] It seems quite probable to me that the giblets, neck and feet would have been used to enrich the broth in which the chickens were cooked.

The herbs and garlic were likely sourced locally, perhaps from a garden in the outer bailey of the castle. The grapes may have come from further afield but nonetheless may still have been English grapes. Indeed, the estates of the archbishop of Canterbury – remember, Roger Walden was archbishop, between 1397 and 1399 – included vineyards at Teynham and Northfleet and records show that right up to the end of the fourteenth century both wine and verjuice (unfermented, unripe grape juice) were being produced there.[17]

Once the chickens were portioned up with a little of the broth, the real magic happened. A powder of expensive, imported, ground ‘sweet’ spices was cast atop, the taste profile of which can best be described as a fusion of delight, elevating the chicken’s flavour and the dish’s status.

For more on powder douce (‘sweet spices’), see this blog post.

Monthly subscribers can get their copy of my modern-medieval recipe for Chyckens in hocche via the Suscribers page (just scroll down and sign in).

It is also available at my Buy Me A Coffee shop.

My second Porchester Castle dish-in-a-pot is Caboches in potage:

Take cabbages and quarter them and simmer them in good broth with minced onions and the white of leeks, sliced and cut small; and add to this saffron and salt and season it with powder douce. (My own translation.)

I’m sure for many, cabbage pottage smacks of the overcooked, stinky, greying mush served in school canteens, and may as a consequence send such folk into paroxysms of disgust. But they should leave such horrors behind and understand that cabbage carefully cooked with leeks and onions, and subtly spiced, was a dish suitable for a medieval king; and today it makes a comforting accompaniment to poached chicken.

Greens or leafy cabbages, known as cole or colewort (similar to spring cabbage today in the UK), were grown as a staple in medieval gardens, but we should note that the cabbages required here are of the headed variety (today we might think of a Savoy or January King).

This is suggested not only by the method of preparation but also by the name Caboches, deriving as it does from Old French for ‘head’. This recipe demonstrates, then, that headed cabbages were being cultivated alongside colewort in the fourteenth century, at least in elite gardens.[18]

The simply written method also leaves plenty of room for adaptation and interpretation. In fact, cooks of the fifteenth century played around with the recipe, specifying capon or beef broth to enrich it, adding marrowbones (ooh, yummy), thickening it with bread crumbs, and – in a version for a lord – carefully tempering egg yolks into the broth to give a silky sauce. (For more detail, see my blog post on cabbage pottage.) In my own modern-medieval version you will find that I’ve taken on board some of these later adaptations.

This recipe is available to monthly subscribers here (just scroll to the bottom and sign in).

It is also available at my Buy Me A Coffee shop.

For my third and final potage, I just had to go sweet, didn’t I? Certainly, the use of sugar in the fourteenth century was a way of proving one’s status, but this dish, though it does use a little sugar in its spice mix, relies primarily upon high-end sweet wines to provide the requisite sugar rush. What’s more, it is a dish that I’m sure most of you will perceive as eminently modern: Peerus in confyt, poached pears in syrup.

Take pears and peel them clean; take good red wine and mulberries, or sanders [a red food colourant], and simmer the pears in this; and when they are cooked, remove them; make a syrup from Greek wine or Vernaccia along with blanch powder – or white sugar and ginger powder – and add the pears to this; simmer a little and serve it forth. (My own translation.)

Pears of various varieties would have been available in or around Portchester. Perhaps the most likely to be used was the Warden, a variety that appears to have stored over winter particularly well and was delicious used in cooking, though not suitable for eating raw.[19]

What I love about this pear potage is the use of ginger which is, dare I say, a more interesting spice to use with poached pears than the typical cinnamon of modern recipes. I am also an ardent lover of ginger and sugar combined the medieval way. Taking the trouble to grind up whole dried ginger pieces rather than rely on shop-bought powdered ginger is really worth the reward.

For more on making blanch powder (blaunche poudour), see my video on YouTube.

So-called Greek wine and Vernaccia were imported, late-harvested wines, made from semi-dried grapes – so, very sweet and raisiny, and having a depth to them that was highly prized. For more information, see my posts on Vernaccia and Greek wine.

I can easily imagine barrels of these wines being stored in the palace storerooms; and dishes of pears in a sweet Vernaccia syrup making their way to the lord’s table on the raised dais at the high end of the great hall.

Maybe, just maybe, I could be there too. Please.

Monthly subscribers can get their copy of my modern-medieval recipe for Peerus in confyt via the Subscribers tab (just scroll down to Archives and sign in).

Alternatively, it is available at my Buy Me A Coffee shop.

I do hope you have enjoyed this little diversion into poky palace pottages, borne from my recent trip to Portchester Castle. And I hope this post may have inspired you to try out my modern-medieval versions of the three dishes from Richard II’s cookery book.

If you have any observations or questions, please leave them in the comments section, below.

Many thanks to Elise Fleming for proofreading my post before it was published. Any errors remain my own.

If you would like to support my independent research and creative work, please consider a small donation, or become a monthly subscriber (the amount you choose is up to you).

Selected bibliography

Laura Ashe, Richard II: A Brittle Glory (Penguin, 2016).

Peter Brears, Cooking and Dining in Medieval England (Prospect Books, 2012).

John Goodall, with contributions by Steven Brindle and Abigail Coppins, Portchester Castle (English Heritage, revised reprint, 2022).

Gina L. Greco & Christine M. Rose (trans.), The Good Wife’s Guide (Le Ménagier de Paris): A Medieval Household Book (Cornell University Press, 2009), Kindle edition.

John Harvey, Medieval Gardens (B. T. Batsford, Ltd., 1981).

A. K. McHardy, The Reign of Richard II: From Minority to Tyranny 1377-97 (Manchester University Press, 2012).

Margaret Roberts, The Original Warden Pear (Eventispress, revised edition, 2018).

Susan Rose, The Wine Trade in Medieval Europe 1000-1500 (Bloomsbury Academic, 2013).

Nigel Saul, Richard II (Yale University Press, 1997).

[1] For an overview of ‘Richard II’s palace’, see the English Heritage guidebook by John Goodhall (details in bibliography), pp. 10-15.

[2] Good historical works on Richard II include the biographies by Nigel Saul and Laura Ashe. I also find the accessible collection of translated documents by A. K. McHardy very useful, as I like to look at primary source material whenever possible. (Details for all three are in the bibliography.) For a fictional reimagining of his troubled reign, I would recommend the novels by Mercedes Rochelle, King Under Siege, and The King’s Retribution – really great page turners!

[3] The term ‘miniature palace’ is from the English Heritage webpage on the history of Portchester Castle.

[5] Citing J. Goodall, The English Castle: 1066-1650 (Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2011), p. 101; https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/portchester-castle/history-and-stories/history/significance/ [accessed 17 July 2024].

[6] Saul, p. 365, n. 39.

[7] Goodall, p.11.

[8] Goodall (p. 12) notes that a 1398 building account records the erection of a louvre ‘to release the smoke’. If there were no chimneyed fireplaces, as is implied by Goodall’s comment on the central fireplace, this would have been essential.

[9] Brears, p. 178 (details in bibliography). Brear’s chapter on ‘The Kitchen’ is exceptionally helpful for understanding the variation in size, construction and facilities of medieval kitchens.

[10] Brears, p. 215. Brear’s chapter ‘Pottage Utensils’ is a must-read.

[11] See the Wikisource Dictionary of National Biography entry for Roger Walden.

[12] See Goodall, p. 33.

[13] The great hall was situated on the first floor (second floor, to US readers) of the two-storey public and service wing of the palace (the south range). It was adjacent to the kitchen, which was located at ground level and extended to the full height of the range, so straight up to the roof. Prepared dishes were carried from the kitchen to the great hall via a stairway in the corner of the kitchen. Evidently, at the ‘high’ end of the great hall (i.e. the opposite end of the kitchen), there was a raised dais upon which the lord’s table was placed, and via the dais one could gain access to the private chambers of the palace in the west range; see Goodall, pp. 10-15.

[14] Description based on that in the guidebook: Goodall et al, pp. 12-13.

[15] See Greco & Rose, p. 289.

[17] Rose, pp. 16-17.

[18] As early as 1322, seed of ‘caboche’ was bought for Lambeth Palace, the residence of the archbishop of Canterbury, alongside seed for colewort; see Harvey, p. 164.

[19] See, generally, Roberts.

Very interesting! As you say I wouldn’t mind 22’x22′ for my kitchen, but considering that some feasts had over 100 dishes… I particularly want to try the cabbage, need to make sure my powder douce is still in good shape.

I read and enjoy the updates even if I don’t common, good to see you and Ray are doing well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. I’m very glad you enjoy the posts.

LikeLike

Portchester is tiny, but lovely. I was convinced that Richard II had stayed there, because I’m sure (although I haven’t checked) that the guidebook refers to the king’s bedroom, which again is a poky little room. Perhaps other kings slept there. My main impression of the kitchen was that I really wouldn’t fancy carrying food up those steps to the hall.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, yes! Having to take all those dishes up those stairs. Exhausting!

We can’t know for sure that Richard never stayed but the evidence is against it. I think that since the building work continued until 1399, we might ask if he would want to stay in a building site. Also right at the end of his reign we know that he was somewhat preoccupied elsewhere.

I think empty ruins always seem small, just as footings for a new building seem ‘too small’. I worked on a building site a number of years ago, a large hall with an apartment attached, and really doubted that the apartment size would be functional. But when it was finished and furnished, it seemed perfectly adequate.

Also I was comparing the Portchester kitchen to a section of my own home, an open plan area which contains my kitchen and dining room/sun room. They are about the same square footage. I realised if it were properly fitted out with professional kitchen stations, and if I had storage room adjacent as the medieval kitchen evidently did (possibly both a buttery and pantry), then with a smallish team of say 6 cooks, we could cater for a grand(ish) dinner for 30 to 50 people reasonably comfortably. But still, we’d have to be ultra organised.

What do you think?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think they had a lot less ‘stuff’ so probably didn’t need as much space, unless they needed to impress. You’re right; it is how you organise and use the space that’s important.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No salad spinner, spiraliser, or bread maker then! 😆

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating! And the dishes sound wonderful!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you 😊.

LikeLike