The fires brenden vpon the auter brighte, That it gan al the temple for to lighte. Chaucer, The Knight’s Tale.

In this new series of short research pieces, I will be shedding a little scholarly light on ingredients from medieval cookery, with particular focus on Richard II’s late-fourteenth-century cookery book Fourme of Cury (‘method of cookery’).

Today, it’s the turn of the heading cabbage.

Heading cabbage

The heading, or headed, cabbage – Latin, Brassica oleracea, var. capitata – was described in 1536 by the French botanist Jean Ruel (aka Johannes Ruellius) as ‘globular and often very large, even a foot and a half in diameter’.[1] It is known for its central head of densely formed leaves.

All types of cabbage, loose-leaved and heading, derive from a wild ancestor, native to coastal Britain,[2] and elsewhere in Western Europe. The origin of the cultivation of cabbages is, however, according to recent genetic research, ‘middle-eastern’. The estimated date for the ‘onset of diversification and breeding of cabbages’ is given as ‘around 400 BC in the middle east’ in a 2022 study.[3]

In literature, the emergence of the headed cabbage, in particular, is much later. Here, I’ll focus on its appearance in medieval England and France.

In fourteenth-century England and France

The name for the heading cabbage in Middle English is caboche, a borrowing from Anglo-Norman French, which means, anatomically speaking, the crown or top of the head.[4] It is to be distinguished from colewort (or cole),[5] the word used for loosed-leaved, not heading cabbage. Colewort was in medieval England widely grown as a garden crop and eaten in pottage, typically whilst the leaves were still young and tender.[6] If you’re British, a comparison to modern-day spring greens might be made. Elsewhere, collards or collard greens are a good comparison.

The Middle French text Le Menagier de Paris, probably written by the French knight Guy de Montigny,[7] is instructive on the types of cabbages available and grown in late-fourteenth-century Paris and its environs. In the section on horticultural advice, the author states that Choulx blans et choulx cabuz est tout ung,[8] that is, white and headed cabbage are one and the same. Though not actually white, the tightly-leaved, pale green, headed cabbages of today – so familiar to us from supermarkets, green grocers, or our own vegetable plot – appear to be something similar to what is being described here.

Le Menagier does also, in its recipe section, refer to pommes de chou, also named choulx rommains.[9] These ‘Roman cabbages’ – eaten in winter, we are told – are evidently also a heading variety, as can be deduced from the use of pommes, literally meaning ‘apple’ or ‘fruit’, giving the sense of a cabbage plant with a rounded form.[10] Nicole Crossley-Holland states they are equivalent to ‘our Savoy cabbage’,[11] the head of which is rather looser than the white cabbage.[12] Whether this type of cabbage was being grown or eaten in medieval England, alongside the solid-headed variety, is difficult to ascertain.

The heading cabbage is mentioned twice in Richard II’s Fourme of Cury, once as the star ingredient for the dish Caboches in pottage (see the recipe link at the end of the post), and once in passing, where the cook instructs that Chebolace, a pottage of onions and leafy greens (erbes), should be cooked ‘as you do cabbages’ – probably meaning a long, gentle simmering in broth.

Peasant fare?

Despite previously implying, in a popular post I wrote a few years ago, that the caboche was peasant food, I feel now I should re-consider its status. The heading cabbage in late medieval England was probably not a widely used vegetable, certainly not in the fourteenth century,[13] and was perhaps only grown in a few elite gardens.[14]

We do know that in 1322 a relatively small amount of caboche seed was bought and sown by Roger, the gardener for Lambeth Palace, the residence of the archbishop of Canterbury, alongside a large quantity of colewort seed.[15] Evidently, though, ‘round cabbage’ (another name for heading cabbage) required a great deal of nurturing – well-manured ground and careful removal of lower leaves – as can be seen from a mid-fifteenth-century text of garden tips.[16]

In London records

Supporting my theory that the heading cabbage was more of a fancy vegetable in medieval England than I’d previously thought is the fact that even by 1420 heading cabbages were being imported into London from the near continent.[17] If widely grown in England, we might ask why it would have been necessary to import heading cabbages from elsewhere.

Of particular note in the London records is that on October 8, 1420, 200 caboches were valued at the same price (3 shillings 4 pennies) as 400 oranges on January 6, 1421.[18] Oranges, brought by Venetian ships, were at this time a great rarity in England, hardly an everyday fruit.[19] To think that a heading cabbage was twice the value of an orange is food for thought, pardon the pun. Moreover, the consignment of 200 heading cabbages was approximately equivalent to 8 days’ wages for a skilled tradesman,[20] making them not especially affordable, other than to the more well-off folk of England.

The red heading cabbage in medicine[21]

There are several medical recipes from thirteenth-century England that incorporate cabbage of one form or another. Three of note, written in Anglo-Norman, use red cabbage (rouge/ruge cholet) as an ingredient in making salves for sores, wounds, and ulcers, one actually in pellet-form, made using May butter.[22] It seems probable that these recipes refer to the headed red, or purple, cabbage, Brassica oleracea, var. capitata F. rubra. Whether these recipes prove that red heading cabbages were being grown or imported for medicine in England during the thirteenth century is difficult to establish, since it is possible the Anglo-Norman texts are drawing upon continental sources, reflecting medical knowledge rather than actual practice in England at that time.

The Fourme of Cury recipe, c.1390

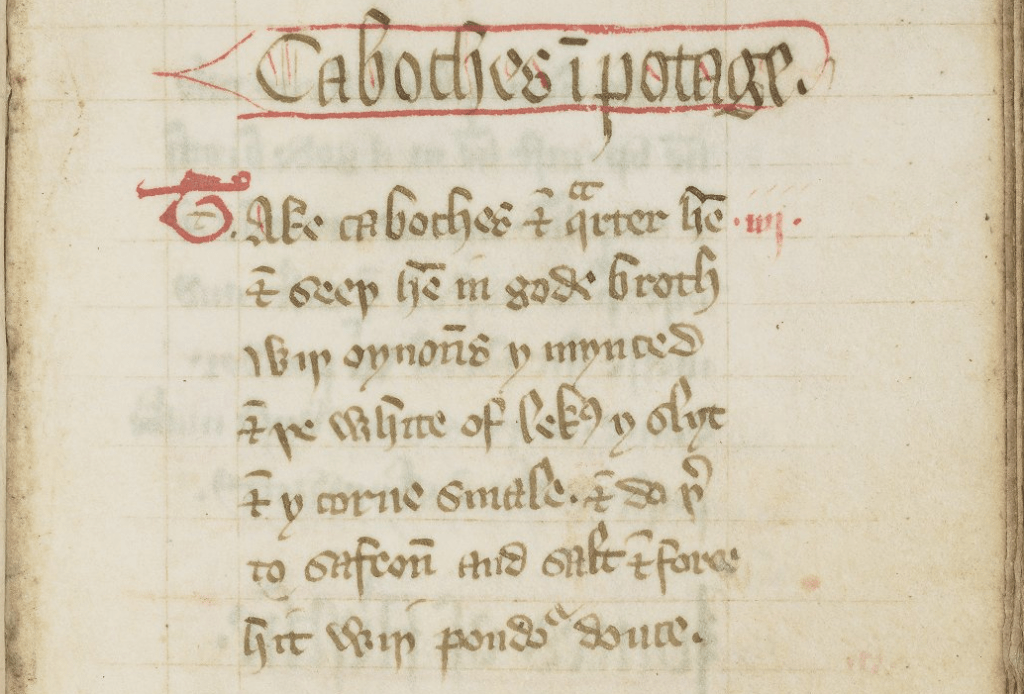

Fourme of Cury has one recipe for using caboche. As far as I understand, this is the earliest recipe in England to use this vegetable.

Take caboches & quarter hem & seeþ hem in gode broth wiþ oynouns ymynced & þe white of lekes yslyt & ycorue smale; & do þerto safroun and salt & force hit wiþ poudour douce.

Headed cabbages in pottage

Take headed cabbages and quarter them and simmer them in good broth with minced onions and the white of leeks, sliced and cut small; and add to this saffron and salt and season it with powder douce.

My own edited text from the John Rylands Library Fourme of Cury (c.1390), English MS 7, folio 13r, with my own translation.

My previously released Modern|Medieval recipe for Caboche in Potage is available free for for monthly subscribers; just follow the links on this blog post.

If you’re not a monthly subscriber, the recipe is available for £1 in my shop.

Support me

If you would like to show your appreciation for this blog post or any other of my outputs, you can support me by making a one-off donation: Yieldeth Me a Cup of Mead.

Select Bibliography

Cai, Chengcheng, Johan Bucher, Freek T Bakker, Guusje Bonnema. ‘Evidence for two domestication lineages supporting a middle-eastern origin for Brassica oleracea crops from diversified kale populations’, Horticulture Research, Volume 9, 2022, pp. 1-15; available as an open-access online article.

Crossley-Holland, Nicole. Living and Dining in Medieval Paris: The Household of a Fourteenth-Century Knight (University of Wales Press, 1996).

Gras, Norman Scott Brien. The Early English Customs System: A Documentary Study of the Institutional and Economical History of the Customs from the Thirteenth to the Sixteenth Century (Harvard University Press, 1918).

Greco, Gina L. & Christine M. Rose (trans.). The Good Wife’s Guide (Le Ménagier de Paris): A Medieval Household Book (Cornell University Press, 2009), Kindle edition.

Harvey, John. Mediaeval Gardens (B. T Batsford, Ltd, 1981).

Hieatt, Constance B. ‘Supplement to the Concordance of English Recipes: Thirteenth Through Fifteenth Centuries’, in Constance B. Hieatt (ed. & trans), Cocatrice and Lampray Hay: Late Fifteenth-Century Recipes from Corpus Christi College Oxford (Prospect Books, 2012), pp. 145-172.

Hieatt, Constance B. & Terry Nutter with Johnna H. Holloway. Concordance of English Recipes: Thirteenth through Fifteenth Centuries (Arizona Center for Medieval & Renaissance Studies, 2006).

Hunt, Tony. Plant Names of Medieval England (D. S. Brewer, 1989).

Hunt, Tony. Popular Medicine in Thirteenth-Century England (D. S. Brewer, 1990).

Le Menagier de Paris, ed. Georgine E. Brereton and Janet M. Ferrier (Clarendon Press, 1981).

Old French-English Dictionary, ed. Alan Hindley, Frederick W. Langley, and Brian J. Levy (Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Sturtevant, Edward Lewis. Sturtevant’s Edible Plants of the World, ed. U. P. Hedrick (Dover Publications, 1972).

Woolgar, C. M. The Culture of Food in England 1200-1500 (Yale University Press, 2016).

[1] See Sturtevant, p. 115.

[2] Brassica oleracea L. in BSBI Online Plant Atlas 2020 [accessed 6 April, 2025].

[3] Cai Chengcheng et al, p. 11.

[4] Note also Middle French caboche, ‘tête’, in Godefroy, Complément; and caboce, ‘head’, in Old French-English Dictionary.

[5] See Harvey, pp. 78, 118, and 164.

[6] Note John Harvey’s observation on the early cropping of colewort directed in the poetic gardening treatise of ‘Master Jon Gardner’, at Harvey, p. 164.

[7] Crossley-Holland, pp. 185-211.

[8] Le Menagier, p. 121 (no. 22). The description of other varieties and their cultivation continues to p. 123, no. 38. For an English translation, see Greco & Rose, pp. 211-13.

[9] Le Menagier, pp. 202-03 (no. 53).

[10] Greco & Rose, p. 280, use the translation ‘Cabbage heads’, which is somewhat confusing, though understandable.

[11] Crossley-Holland, p. 46, n.1.

[12] Sturtevant, p. 115, observes that the ‘Roman varieties were not our present solid-heading type but loose-headed and perhaps of the savoy class’.

[13] The first English recipe to use caboche as an ingredient is the late-fourteenth century Fourme of Cury one, mentioned above. There are just eight further English medieval recipes that do so during the entire fifteenth century. See Hieatt, Concordance, p. 17, and Hieatt, ‘Supplement’, p. 150.

[14] The heading cabbage is not mentioned in either of the two main horticultural records of fourteenth-century England, neither the gardening treatise of ‘Jon Gardener’, nor the botanical records of Friar Daniel, whereas colewort (kale) appears in both; see Harvey, pp. 169 and 173.

[15] Harvey, pp. 86 and 164.

[16] Harvey, p. 164.

[17] Gras, pp. 499, 502, 504, 505, 506, and 508. Imported between the 8th October 1420 and 29th January 1421, by Hanse merchants, i.e. merchants operating in the Baltic Sea and North Sea areas.

[18] Gras, pp. 499 and 506.

[19] Woolgar, pp. 106 and 209.

[20] Based upon the calculations of the UK’s National Archives’ Currency converter: 1270–2017.

[21] Note that white heading cabbages are mentioned in a fifteenth-century English manuscript of medical texts held at the British Library. See Hunt, Plant Names, p. 59, Cabus: Hunt gives, ‘anglice whit caule or chabochys’ (‘in English, white cole or caboches’). For an overview of the manuscript, see p. xxxi, no. 26. Unfortunately, I have not been able to check the manuscript.

[22] Hunt, p. 67, no. 15, which gives the instruction to make pelettes with bure de may; p. 280, no. 108; and pp. 291-92, no. 219, which also uses May butter but also virgin wax and olive oil to make the salve. My search for the use of heading cabbage in English medieval medical texts is by no means comprehensive. These are just a few examples.

Fascinating! I had no idea about any of this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating! I had no idea about any of this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m loving these London port records (and the Southampton ones I’ve got a copy of, too). All sorts of information on “foreign” goods.

LikeLike

Cabbages are much maligned, but there’s one in my kitchen ready for dinner this evening. I can’t grow them, though, as the slugs like them far too much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think that was implied by the fifteenth-centuary garden tips. Little varmints!

LikeLiked by 1 person

When I was growing up in Alaska we had enormous cabbages – you wouldn’t think of Alaska as a great place to grow vegetables, but the extremely deep (10m!) and extremely rich soil and the near 24-hours of sunlight at the peak of summer made most things grow like mad. I believe one of the largest ever grown there was 60 kg and 2 meters diameter. Even ‘quarter hem’ would be woefully insufficient! They had huge leafy skirts, but the central portion was that tight head, like your picture at the top.

And those do sound relatively fancy, especially in the 1400s. I wonder if those gentlemen managed to make the connection between cabbage and ‘the vapours’? They seemed to have so many digestive ailments maybe it hardly registered.

Finally, thanks to your previous episodes and articles I was pretty much able to read the original recipe and figure what it was saying except for ‘yslyt & ycorue’ and now I know (TM). I’ve learned a lot from you over the years!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! Massive Alaskan caboches, who’d’ve thought?!

The ‘vapours’ and cabbages in the medieval period… somewhere in my brain there’s a recollection of this. If it comes to me, I’ll let you know.

Thank you for your kind words and support. It’s really appreciated. It always makes me smile when someone says they learn something from my work. I’m sure you can relate to that yourself.

LikeLike