Hello everyone!

I’ve been hard at work trying to get back to a more regular way of writing and researching after a tricky year or more of poor health.

One area of research I have been focusing on recently is medieval cheesemaking. And so I want to share with you my translation of a section of the Middle English verse translation of the fifth-century Latin work on agriculture by the Roman author Palladius.

Not a great deal is known about Palladius, though he did write from personal experience as a farmer in addition to drawing upon other Latin sources on agriculture. His treatise Opus Agriculturae is the latest of Roman works on the subject and this may explain why it was the most widely distributed of these in medieval Europe, being translated not only into Middle English but also Italian, Catalan and other languages.

Prospect Books published John Fitch’s modern English translation of Opus Agriculturae in 2013, and in there you will find an introduction that places the work in context.

We know even less about the English translator of Palladius, though he may have been carrying out his work, titled On Husbandrie, not long after Geoffrey Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales, so perhaps in the early fifteenth century.

The edition by Rev. Barton Lodge with Sidney Herrtage, based on a surviving mid-fifteenth-century manuscript (Bodleian Library MS. Add. A. 369), and published for the Early English Text Society in 1873/1879, is kindly made available as a facsimile on Internet Archive.

I use this edition as the basis for the Middle English text below (written in italics). It is, as you see, provided with my own, fairly literal, interlinear modern English translation.

I’ve provided a few footnotes and square-bracketed notes within the translation to help with understanding. The poem’s line numbers appear in square brackets at the beginning of each line of Middle English.

I am very happy for you, my lovely readers, to leave comments or ask questions in the comments section at the end of the post.

So if you do have any questions about the Middle English text, my translation, or on how we might best interpret this text in the context of medieval cheesemaking, please don’t hesitate to send them to me. Hopefully, we can get a good conversation going. Though please note that I may be away from my computer or phone for a day or so as I am having a cataract removed today.

De casio faciendo.

On the making of cheese.

[141] Alle fresshe the mylk is crodded now to chese

All-fresh, the milk is now curdled to cheese

[142] With crudde of kidde, or lambe, other of calf,

with rennet of kid, or lamb, or calf,

[143] Or floure of tasil[1] wilde. Oon of hem chese,

or flower of wild teasel.[2] One of them choose,

[144] Or that pellet[3] that closeth, every half

or the [rennet-]membrane that closes, on all sides,

[145] The chicke or pyjon crawe, hool either half.

the chicken or pigeon crop – whole or half [i.e. of the membrane].

[146] With figtree mylk, fresshe mylk also wol turne.

With fig tree milk, fresh milk will also turn [i.e. curdle].

[147] Thenne wrynge it, presse it under poundes stone;[4]

Then wring hit, press it under a stone of one pound

[148] And, sumdel sadde up doo it in a colde

and, somewhat firmed, put it away into a cold

[149] Place, outher derk, and after under presse

and dark place; and after, under pressure,

[150] Constreyne it efte, and salt about it folde;

constrain it again, and enfold salt around it.

[151] So sadder yet saddest it compresse.

Thus yet firmer it shall be compressed firmest.

[152] Whenne it is wel confourmed to sadnesse

When it is well-moulded by firmness,

[153] On fleykes legge hem ichoone so from other,

store them on frames, each one apart from the other,

[154] That nere a suster touche nere a brother.

so that neither a ‘sister’ nor a ‘brother’ touch.

[155] But ther the place is cloos is hem to enclude,

But there the place is shut up, enclosing them.

[156] And holde oute wynde although he rowne or crie,

And keep out Wind, though he roams and cries.

[157] So wol thaier fattenesse and teneritude

Thus their fatness and tenderness will

[158] With hem be stille; and yf a chees is drie,

remain with them. And if a cheese is dry,

[159] Hit is a vyce, and so is many an eye

it is a flaw; and so is many an eye [i.e. many holes],

[160] Yf it see with, that cometh yf sonnyng brendde,

if it’s seen with them; that comes if there’s bright sunlight,

[161] Or moche of salt, or lite of presse, it shende.

or too much salt or too light a press – it is ruined.

[162] An other in fresshe mylk to make of chese

Another, to make a cheese in fresh milk,

[163] Pynuttes grene ystamped wol he doo;

crushed young pine nuts he will add.

[164] An other wol have tyme a man to brese

Another man will have thyme to bruise,

[165] And clensed often juce of it doo to

and oft-purified juice from it he may add too,

[166] To tourne it with; to savor so or soo;

to turn [i.e. curdle] it with. To flavour this way or that,

[167] It may be made with puttyng to pigment,

it may be made by adding spices,

[168] Or piper, or sum other condyment.

or pepper, or some other seasoning.

If you would like to help cover costs for my independent research you may do so either by a one-off donation or as a monthly subscriber.

[1] Translating Latin cardui, perhaps originally, in a Mediterranean context, referring to the thistle head of the cardoon, Cynara cardunculus, still used today in cheesemaking, but perhaps interpreted in its Middle English context as the wild teasel, Dipsacus fullonum (= Dipsacus sylvestris Huds.), or something similar, though in general medieval plant names are notoriously difficult to pin down. See Hunt, p. 68, Cardo; and also theDictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources, carduus, ‘1 thistle or sim.’ logeion.uchicago.edu/carduus [accessed 14 July, 2025].

[2] Or, thistle.

[3] Middle English Dictionary, pellet n. 1(a)‘The rennet membrane of a chicken’, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/middle-english-dictionary/dictionary/MED32781/track?counter=1&search_id=2021624 [accessed 13 July, 2025].

[4] scorne in the edited text, which does not make sense to me, other than that it serves the rhyming scheme better than my choice of stone. Perhaps scorne is a misreading of the manuscript, but I cannot check it, as it hasn’t been fully digistised. It is possible storne, as a variant of stone, is meant. The letters c and t are almost indistinguishable in some medieval hands.

Select bibliography

Hunt, Tony. Plant Names of Medieval England (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1989).

Lodge, Barton & Sidney J. H. Herrtage, eds. Palladius On Husbondrie, 2 vols, Early English Text Society, Original Series 52 and 57 (London: Trübner & Co., 1873, 1879).

I had no idea there were so many plant-based curding agents, And I must say that cheesemakers dressed a lot more nattily in the 1450’s…

LikeLiked by 1 person

My last few responses here before cataract surgery: Neither did I. It’s a fascinating text. Quite difficult at first to translate due to false friends but got there in the end.

LikeLiked by 1 person

cataract surgery? You ARE having a time of it, aren’t you? If you trust your opthomologist, it’s pretty straightforward. My mother, a voracious reader, had it in in 2 batches in her early 90’s. Without, one of us would probably have been dead a lot earlier.

All spare good wishes forwarded.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your translations are always a highlight, I love seeing the original text.

It’s kind of funny that this is just ‘take milk, add one of these many many curdling agents, press it, and here’s all the things that can go wrong. Oh yeah and you can add spices’. As you’ve pointed out before, getting actual specifics is quite rare, and so it is here.

Good luck on your surgery! Thankfully that is fairly routine these days, or as routine as it can be given where they’re sticking stabby things.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suppose in his fourteen books on husbandry Palladius had a great deal to cover, so perhaps we should forgive him for his brevity 🤣. I wonder if, as a farmer, he ever made cheese himself or just garnered the information from his wife. I don’t know enough about 5th-century Roman life so will need to pass on that for now.

Thanks for the good wishes. Yes, the surgery went very well. ☺️

LikeLike

I meant to say that as far as I’m aware, the Middle English translation of this section of Palladius is the closest thing we have to a late medieval English cheese manual.

LikeLike

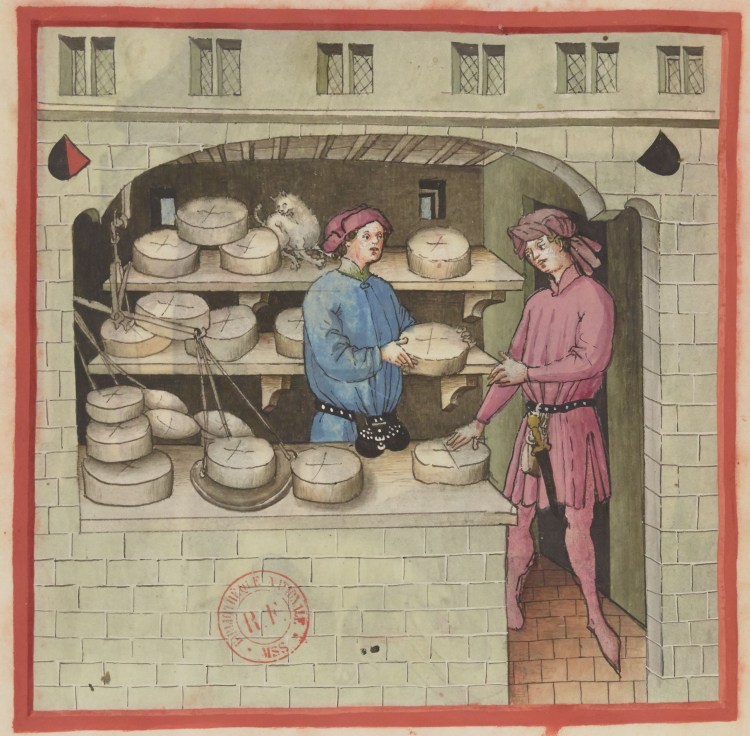

It makes cheesemaking sound so easy, but I doubt that’s the case. Clearly the cheesemonger in the illustration hasn’t read the bit about brothers and sisters not touching one another.

I hope the surgery went well. Loads of my friends have been having it done recently and it’s always gone well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha! I liked the brother and sister bit. It gave the passage a real sense of humanity, that and the Wind roaming and crying.

Palladius’ predecessor Columella wrote more detail on how it was done but I do like the information on types of rennet for turning the milk. Quite a few vegetarian options!

Surgery has gone very well. To quote a favourite Kate Bush song of mine, All the colours look brighter now.

LikeLiked by 1 person