The fires brenden vpon the auter brighte, That it gan al the temple for to lighte. Chaucer, The Knight’s Tale.

In this new series of short research pieces, I will be shedding a little light on ingredients from medieval cookery.

The starting point will be the rarely used ingredients that appear in the English cookery book Fourme of Cury (the title essentially means the correct method of cooking).

This largely Middle English text was commissioned by King Richard II (r. 1377-1399) and compiled around 1390 by his master cooks, with the assent of his maysters of physyk, his physicians.

The latter will have a bearing on the ingredients chosen, as I will also address any use of the ingredient in a medieval medical context.

Whenever possible, I’ll include at the end of the post my modern-medieval recipe that incorporates the ingredient. The recipe may be in a development stage.

Long pepper

The dried fruit spike of Piper longum, often called Indian long pepper or pippali, is mentioned in Sanskrit writings as early as 1000 B.C.[1] It arrived in medieval England from the Indo-Malayan region, via Venetian galley ships.

It is harvested whilst green and then dried in the sun where it turns dark brown. The spikes, looking like mini pine cones, measure about 2½ to 4cm (1 to 1½ inches).

Flavour profile: peppery hot with a lingering warmth; a woody, earthy pungency; a hint of sweetness. If you chew it (as I did), it will numb your tongue for a while![2]

In medieval records

We have two customs records of long pepper’s importation into London dating to 1421:

A certain Philippo Tayper[3] brought in ‘one barrel of long pepper’ in a small cargo of spices which also included two bales of ginger, one barrel of sugar candy, two of mace, and a sack of cardamom.[4]

Francisco Balby imported a very large and valuable cargo of luxury cloths and spices that included just ‘one bale of long pepper’.[5] When we compare this to his thirty-three bales of ‘pepper’ – evidently black pepper (Piper nigrum) – we may conclude that at this time long pepper was enjoyed less often, and perhaps by fewer, English elites than was the longstanding culinary go-to, black pepper.

In cookery

Pur fayre ypocras (189). Troyȝ vnces de queynel & iij vnces de gyngeuer, spyknard, le pays dun denerer, garyngale, clowes gylofre, poeure long, noieȝ mugadeȝ, maȝioȝame, cardemonij, de chescun j quarter donce, grayne de paradys, flour de queynel, de chescun demi vnce; de toutes soit fait poudour et cetera.

To make hippocras. Three ounces of cinnamon [or cassia] and three ounces of ginger; spikenard, a pennyworth; galangal, cloves, long pepper, nutmeg, marjoram, cardamom, one quarter ounce of each; grains of paradise, cinnamon [or cassia] buds, half an ounce of each; from all one must make a powder, etc.

Fourme of Cury, recipe 189, from the John Rylands Library, English MS 7 (late 14th-century). My own edition and translation.

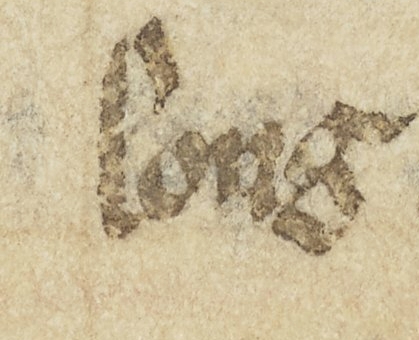

In Fourme of Cury, long pepper is only specified once, as poeure long (see images above), in the text’s only recipe written in Anglo-Norman.[6] I say a recipe but, as you see, it is actually just a list of all the spices, by weight, that are ground into the powder that gave life to this spiced, sweetened and filtered wine.

Though cinnamon and ginger were the dominant spices in this version of hippocras, long pepper would have given a complementary degree of heat or kick, and (to my palate) a hint of desirable earthiness, too.

In medicine

Finally, on long pepper, we should note two of its medicinal uses in fifteenth-century English texts. In the Middle English version of Chirurgia magna (‘great work on surgery’), a Latin work written by French physician Guy de Chauliac (c.1300-1368), it is an ingredient for making ‘purgings for the head’.

It is also an ingredient in a medical recipe from a collection preserved in a mid-fifteenth-century, Stockholm Royal Library manuscript, where it is to be taken with ginger and galangal ‘for the stomach’.[7]

Recipe

As long pepper is considered to be more complex than black pepper, you might want to avail yourself of some and use it instead or alongside black pepper. Long pepper is more widely available than it was a few years ago, especially online.

Here, I’ve substituted long for black pepper in my rendition of Fourme of Cury’s Peuorat, a pepper sauce served with veal and venison, though I actually ate it with chicken wings!

Please note, this was an experimental, first stage development recipe, made whilst on holiday away from my home kitchen. I think it could be tweaked to improve it. For example, I would consider combining both long and black pepper, perhaps a 50-50 ratio, and reduce the amount of bread by half for a thinner condiment.

Peuorat for veel & venesoun (133). Take brede & fry hit in grece; drawe hit vp wiþ broth & vyneger; take þerto poudour of peper & salt & set hyt on þe fyre; boyle it & messe it forth.

Pepper sauce for veal and venison. Take bread and fry it in fat; blend it with broth and vinegar; to this add powder of pepper and salt, and set it on the fire; boil it and serve it forth.

Fourme of Cury, recipe 133, from the John Rylands Library, English MS 7 (late 14th-century). My own edition and translation.

Ingredients

1 level tablespoon freshly ground long pepper

1 slice of bread (I used a gluten-free multi-grain bread as that was all I had)

1 teaspoon of butter for frying

200ml chicken stock (beef stock/broth would be good; vegetable stock for non-meat eaters)

50ml apple cider vinegar (I would normally have used white wine vinegar)

pinch of salt

1 teaspoon of butter at the end

Method

I broke the bread into pieces and slowly fried it in the butter until it turned golden brown.

Whilst this was happening, I ground up some whole long pepper spikes with a stone pestle and mortar. (I needed Ray to help me, as my grip is not as good as it used to be.)

I sieved it through a tea strainer to get a fine powder.

I put the chicken stock, cider vinegar and fried bread all into a blender, and blended until completely smooth.

I put the liquid into a small saucepan with a level tablespoon of the ground long pepper and a pinch of salt.

Over a medium heat I brought the sauce, whilst stirring, to just below boiling point; then turned it down to low and cooked it, still stirring, until it thickened.

I added a knob of butter for extra gloss.

I poured the sauce into a jug and served it with my chicken. It was good – even Ray liked it!

A note on gluten-free bread in medieval type, bread-based sauces. It does tend to make sauces a little gloopy, especially if you cook the sauce for several minutes – I’m not sure if wheat bread would behave exactly the same. I think for this reason, I would halve the bread in this recipe. There is also the option to strain the sauce.

Would you like to say “thank you”?

Would you like to show your support for my independent research? If so, you can make a small donation or consider becoming a monthly subscriber (you set the amount yourself).

Bibliography

Gras, Norman Scott Brien. The Early English Customs System: A Documentary Study of the Institutional and Economical History of the Customs from the Thirteenth to the Sixteenth Century (Harvard University Press, 1918), available via Internet Archive [accessed 10 March, 2025].

Lakshmi, Padma, with Judith Sutton and Kalustyan’s Spice Shop, The Encyclopaedia of Spices and Herbs: An Essential Guide to the Flavors of the World (Harper Collins, 2016), Kindle edition.

[1] Lakshmi, p. 222.

[2] See also Lakshmi, pp. 230-31. Lakshmi notes it has a strong aroma of ginger. Personally, I don’t get this, but of course smell – and taste – are individual and subjective.

[3] The name Tayper is an abbreviated form of presumably an Italian name of the period, which may also have been Anglicised in this London controller’s customs document.

[4] Gras, p. 512.

[5] Gras, p. 511.

[6] Anglo-Norman is the modern name given to the dialect of medieval French that evolved in England after the Norman Conquest (from 1066).

[7] For the medical uses, see the quotations at the online Middle English Dictionary, lō̆ng-peper n., 1(b).

The pevorat sounds delicious! Bread crumbs are tricky; my efforts at Sawse Madame turned out a bit gritty (not enough grinding), but not gooey.Re-reading the recipe Pur fayre ypocras: Ginger is a problem for me. Unless the Mamluks were smart enough to start growing their own, it would’ve dried out a lot on its camelback or sea voyage. Do you think the court purveyors were buying it wizened and whole, or in powder form? I just weighed a race I have on hand, and 3 oz. is a LOT of ginger. You’d hardly taste anything else…And what’s the market rate on spikenard, anyway?

Are you still Floridian? Hope you’re having a good time!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello, yes, still in the Florida sunshine 😊.

On ginger, it would likely have been large whole rhizomes, the English spiciers grinding it on purchasing it from the Venetian suppliers; or elite households would have bought it whole and grinded it themselves, for food or medicine.

It’s worth noting that an English recipe for blanche powder (sugar + ginger, very finely ground) directs the maker to *peel* the ginger. I’ve in the past assumed that meant the dried ginger needed to be rehydrated somewhat, which does today allow one to scrape away the skin. Now, I’m wondering if it was necessary to peel away the wizened skin of large rhizomes to get to the better preserved part.

We should also note that a medical recipe for gingerbread (ginger toffee) uses a ridiculous amount of ginger, which has always suggested to me that it had lost some of its intensity by the time it arrived in England from India.

I will one day carry out an experiment to see how a piece of dried ginger tastes before and after sorting it for a year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Consider that, to truly appreciate ginger in medieval London, you should spray the rhizome with salt water 2-3 times, drying it out each time, then stick it under the collar of a large dog that you then talk for a long walk.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🤣🤣🤣

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not sure on the spikenard market rate. I will need to find out. It evidently came from Spain.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with you on long pepper; i don’t get ginger notes, rather more floral and woodsy. Cubebs have a distinct gingeriness to them, but they don’t get used much in the FOC. I made you a little regalo; it might just pay for a Cubano sandwich.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting on the floral notes. I will keep smelling and chewing my newly purchased long peppers, for which your kind regalo will be used.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You interpret an ingredient as cinnamon or cassia. The medieval Islamic cookbooks distinguish between them. Do any of the Christian ones? Do we have any evidence on which was being used?

LikeLiked by 1 person

In a culinary context it is not possible to distinguish between the two until the 15th century. Non-culinary works do make a distinction. I’ve written a post that touches on this; if you’d like to check it out, it’s here https://modernmedievalcuisine.com/2024/08/25/cassia-buds-the-flower-of-medieval-spices/.

LikeLike

The Islamic cookbooks make the distinction at least as early as the 10th century (al-Warraq).

LikeLike

Thanks. I’ll check my copies when I return home.

LikeLike

Do you discuss this in your book on the spice trade? I’ve got a copy, so I’ll refresh myself on its contents.

LikeLike

I don’t have a book on the spice trade. I do have, with my wife, a

medieval (and renaissance) cookbook: /How to Milk an Almond, Stuff an

Egg and Armor a Turnip/

http://www.daviddfriedman.com/Medieval/To_Milk_an_Almond.pdf.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Must be confusing you with someone else. Thanks for the link.

LikeLike

I’m getting you mixed up with Paul Freedman. Sorry.

LikeLike

I would be interested in understanding the Islamic use of the various cinnamons. Presumably there are different Arabic words for cassia and ‘true’ cinnamon. If you would enlighten me, I’d very much appreciate it.

LikeLike

I’m actually away from my study at the moment. I have written a fairly lengthy entry for ‘cinnamon/cassia’ in a Compendium I hope to include in a forthcoming book.

LikeLike

It was Bartholomew the Englishman (13th-century) who made a distinction between a smaller and larger cinnamon, the former being more ‘subtle’ (delicate) and expensive and the latter harder and sweeter, as well as cheaper.

LikeLike

I first learned of long pepper from your Youtube videos! And yes, it’s better than black peppercorns. Good to see it first in line for ingredients.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s worth revisiting all my recipes and substituting or combining long for/with black pepper.

LikeLike